“Ntlonti’s work, which spans across painting, performance, sculpture and sound, is preoccupied with structural impossibility and limit. Her abstraction hints at the consistency in the violence of the structure that displaces, dislocates and dispossesses at all levels, including corporeal, political, spiritual, psycho-social, and territorial.” - Vusi Nkomo

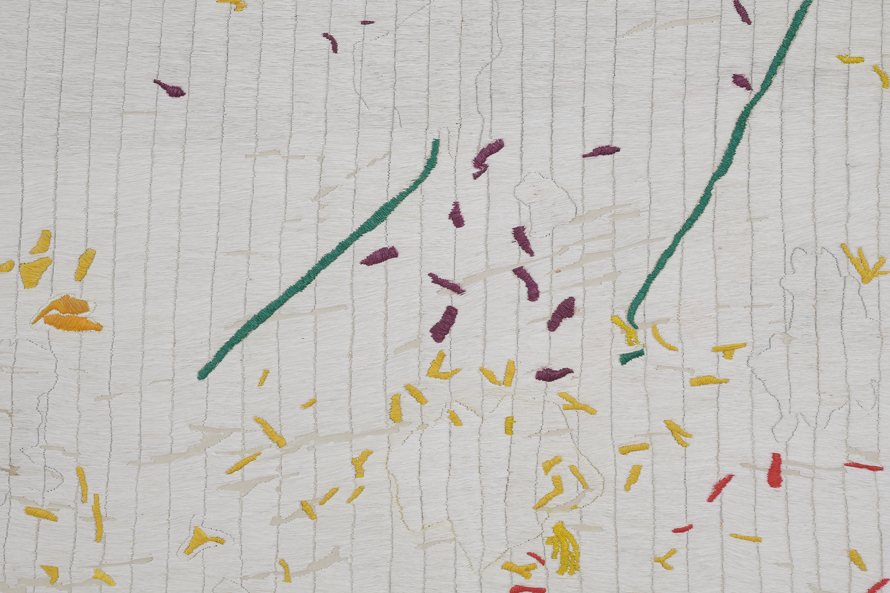

Working in layers of paint and paper, Ntlonti gradually builds up her works on canvas by intuitively applying and stripping away material to reveal chance compositions which refer to the textures and hues of the vernacular cob architecture found in the Eastern Cape of South Africa.

Resembling topographical charts or maps, the paintings conjure landscapes imbued with nostalgia and longing, reflecting Ntlonti’s complicated relationship to her ancestral amaXhosa homeland, which is at once both familiar and strange. Through the act of stitching (using thread from deconstructed vegetable sacking) Ntlonti seeks to mend, to heal over, the scars of generational traumas caused by the internal displacement and scattering of communities.

To date, Ntlonti has had five solo exhibitions: Gqal’emgqubeni (2025), Inzonzobila (2024), Vuthulula (2021), Nothwala impahlana (2020) and Kukho Isililo Somntu II (2017). Recent group exhibitions include Lifelines at Eva Livijn Art Space, Stockholm (2026), We, The People: 30 Years of Democracy in South Africa at Norval Foundation, Cape Town (2025), Eighteen Painters at Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York (2024) and The Future is Behind Us at A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town (2022).

In 2024, Ntlonti was awarded the Spirit Now London Acquisition Prize announced at Frieze London, with an acquisition by the Women’s Art Collection at the University of Cambridge (UK).

—

curriculum vitae

1993 Born in Cape Town, South Africa

education

2017 Bachelor of Fine Art, University of Cape Town

solo exhibitions

2025 Gqal’emgqubeni, blank projects, Cape Town

2024 Inzonzobila, blank projects, Cape Town

2021 Vuthulula, WHATIFTHEWORLD, Cape Town

2020 Nothwala impahlana, WHATIFTHEWORLD, Cape Town

2017 Kukho Isililo Somntu II, blank projects, Cape Town

group exhibitions

2026 Lifelines, Eva Livijn Art Space, Stockholm

2025 Fragment II, Commune Gallery, Vienna

2024 We, The People: 30 Years of Democracy in South Africa, Norval Foundation, Cape Town

2024 Eighteen Painters, Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York

2023 The Orange River, SixtySix London, London

2022 The Future is Behind Us, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town

2022 Seeds of the Fig, WHATIFTHEWORLD, Tulbagh

2022 Home Strange Home, WHATIFTHEWORLD, Tulbagh

2022 The Phoenix Runway, WHATIFTHEWORLD, Cape Town

2021 Space & Place, Galerie EIGEN + ART, Leipzig

2021 021 - 2021, Stevenson, Amsterdam

2019 “SANS”, Open24hrs, Cape Town

2019 The Female Line, SMAC Gallery, Cape Town

2019 Unresolved Category, Gallery MOMO, Cape Town

2019 Do you know these 5 Women Artists?, North West University Gallery, Potchefstroom

2018 Sunday Service, Gallery of the University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch

2017 Greatest Hits, AVA Gallery, Cape Town

2016 Barclays Absa L’Atelier Art Awards, Absa Art Gallery, Johannesburg

2015 Sasol New Signatures, Pretoria Art Museum, Pretoria

selected performances

2019 ... Between my finger and my thumb the squat pen rests. I'll dig with it, Infecting the City, The Slave Lodge, Cape Town

2016 The Portrait (Performance with iQhiya), Documenta 14, Kassel and Athens

2016 iQhiya, AVA Gallery, Cape Town

2016 Ukuzila: ndiyakuthanda sis'Nosipho, ndiyakuthanda sis’wam, Infecting the City, Cape Town

2016 The Commute Pt II, Institute For Creative Arts, University of Cape Town, Cape Town

2016 The Commute Pt I, Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town

2016 The Portrait II, V & A Waterfront, in association with Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town

2016 The Portrait I, Greatmore Studios, Cape Town

2016 Echoing Voices from Within: Rhodes Must Fall, University of Cape Town, Cape Town

— selected press

2024 Spirit Now art prize announces latest winners. Lux Magazine[online].

2024 O’Toole, S. Seven must-see exhibitions in Cape Town this month. Art Basel [online] (published 13 February 2024).

2024 Nkomo, V. Izonzobila: A tear in the world. The Mail & Guardian (published 10 February 2024).

2022 The Future is Behind Us. A4 Arts Foundation (published December 2022).

2022 ARTIST IN RESIDENCE: ASEMAHLE NTLONTI. Krone Cap Classique [online] (published 14 June 2022).

2020 Nkomo, V. New Lands: Asemahle Ntlonti’s ‘Nothwala impahlana’. ArtThrob [online] (published 2 November 2020).

2019 Pather, J & Boulle, C. Acts of Transgression: Contemporary Live Art in South Africa. Wits Press (published 2019).

2017 Gamedze, T. Ijeremani Lam by Senzeni Marasela & Kukho Isililo Somntu II by Asemahle Ntlonti. Contemporary& [online] (published May 2017).

blank is pleased to present Gqal’emgqubeni, a solo exhibition by Asemahle Ntlonti and her third with the gallery.

Loving one’s home is not about being fixed into a place, but rather it is about becoming part of a space where one has expanded one’s body, saturating the space with bodily matter: home as overflowing and flowing over.

In her introduction to Queer Phenomenology, Sara Ahmed argues that orientation is “a question not only about how we ‘find our way’, but how we come to ‘feel at home’.” For Ahmed, a core aspect of being oriented is feeling the ability to inhabit a space, to be able to ‘expand’ into an area, as opposed to feeling a discomfort or alienation that inhibits one’s body from stretching into itself. Engaging ‘migrant orientation’ as a “lived experience facing at least two different directions: toward a home that has been lost, and to a place that is not yet home”, Ahmed’s phenomenology echoes with colonised, diasporic, marginalised and queered identities everywhere.

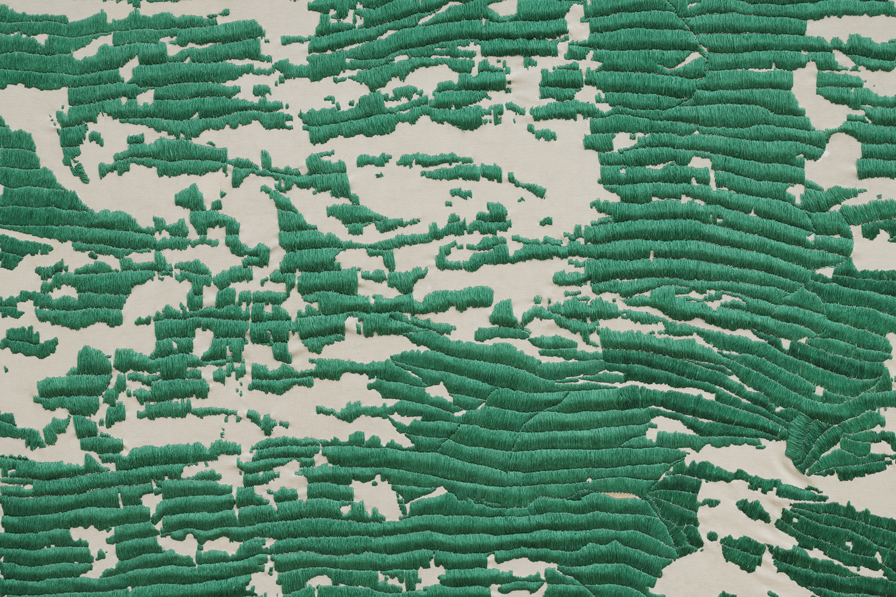

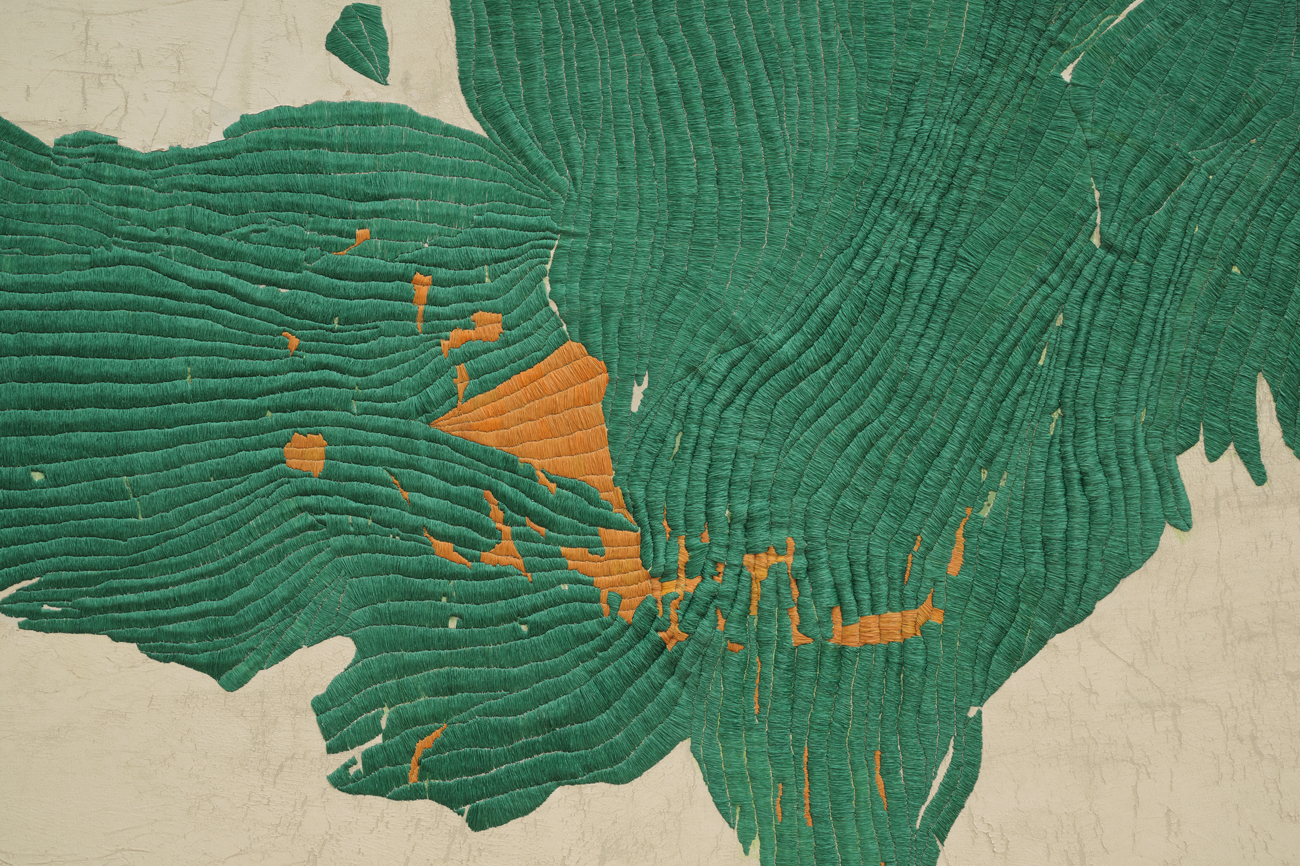

Over the past few years, Asemahle Ntlonti’s laboured surfaces — painted, torn, sewn — have attempted the revival of her lost familial home in Mqonci, Ngcobo, in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Echoing the gentle palettes and aged textures of her village’s rondavel walls, the pastel shades peel and fade on canvases plied with plastic stitches made from the threads of fruit and veg bearing polypropylene bags, or ingxowa. These stitches, collectively creating swollen softened textures, rupture the canvas surfaces while simultaneously performing a kind of repair. In Gqal’emgqubeni, the presence of Ntlonti’s stitch is further emphasised, with swathes of dark green stitching stark against light backgrounds in irregular clumps, mapping imagined land formations in soft quiltlike textures.

The desire to expand, to stretch into oneself, and to become oriented, even while potentially facing “two different directions”, gives intensity and gentle force to Ntlonti’s practice. Over the last decade, she has engaged myriad strategies to create re-oriented studies that hone in on details of collective Southern African historical realities as well as more personal and ancestral questions regarding displacement and alienation. The artist’s early interventions with scale and repetition, and later examinations of texture and colour, show an interest in the labouring of reference points — usually her own memory cues — until they are made strange, and sometimes altogether lost. The resulting forms, as re-readings or unlearnings of place and object, enact a desire for a different kind of mapping of the world, in which more expansive (in)habitation is possible.

[Excerpt from Orientation and “Homeplace” in the work of Asemahle Ntlonti by Thulile Gamedze (2025)]

-

Loving one’s home is not about being fixed into a place, but rather it is about becoming part of a space where one has expanded one’s body, saturating the space with bodily matter: home as overflowing and flowing over.

Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology

In her introduction to Queer Phenomenology, Sara Ahmed argues that orientation is “a question not only about how we ‘find our way’, but how we come to ‘feel at home’.” For Ahmed, a core aspect of being oriented is feeling the ability to inhabit a space, to be able to ‘expand’ into an area, as opposed to feeling a discomfort or alienation that inhibits one’s body from stretching into itself. Engaging ‘migrant orientation’ as a “lived experience facing at least two different directions: toward a home that has been lost, and to a place that is not yet home”, Ahmed’s phenomenology echoes with colonised, diasporic, marginalised and queered identities everywhere.

Over the past few years, Asemahle Ntlonti’s laboured surfaces — painted, torn, sewn — have attempted the revival of her lost familial home in Mqonci, Ngcobo, in the Eastern Cape of South Africa. Echoing the gentle palettes and aged textures of her village’s rondavel walls, the pastel shades peel and fade on canvases plied with plastic stitches made from the threads of fruit and veg bearing polypropylene bags, or ingxowa. These stitches, collectively creating swollen softened textures, rupture the canvas surfaces while simultaneously performing a kind of repair. In Gqal’emgqubeni, the presence of Ntlonti’s stitch is further emphasised, with swathes of dark green stitching stark against light backgrounds in irregular clumps, mapping imagined land formations in soft quiltlike textures.

The desire to expand, to stretch into oneself, and to become oriented, even while potentially facing “two different directions”, gives intensity and gentle force to Ntlonti’s practice. Over the last decade, she has engaged myriad strategies to create re-oriented studies that hone in on details of collective Southern African historical realities as well as more personal and ancestral questions regarding displacement and alienation. The artist’s early interventions with scale and repetition, and later examinations of texture and colour, show an interest in the labouring of reference points — usually her own memory cues — until they are made strange, and sometimes altogether lost. The resulting forms, as re-readings or unlearnings of place and object, enact a desire for a different kind of mapping of the world, in which more expansive (in)habitation is possible.

[Excerpt from Orientation and “Homeplace” in the work of Asemahle Ntlonti by Thulile Gamedze (2025)]

failure (to cohere)

Text by Vusi Nkomo

The profound stakes of Asemahle Ntlonti’s practice point to a symbiosis between a fundamental failure and a specific structure of domination that inaugurates our global modernity and anticipates our current catastrophe. For Ntlonti, the violence that founds this order lingers within the scars marking the surface of this land. This naked force, in Orlando Patterson’s words, is constitutively an “…ontological first moment—or a point of paradigmatic origin”, to borrow from theorist Frank Wilderson in his essay Biko and the Problematic of Presence (2008). Perhaps it is this prior-ness that perplexes: how can something so essential and foundational escape all the modes of inquiry that seek to render it conceptually coherent, that is, sayable and thinkable?

Ntlonti’s work, which spans across painting, performance, sculpture and sound, is preoccupied with structural impossibility and limit. What consistently appears as cracks in the composition, we might read as the woundedness of the ‘pained’ landscapes against the (im)possibility of repair. Ntlonti’s abstraction hints at the consistency in the violence of the structure that displaces, dislocates and dispossesses at all levels, including corporeal, political, spiritual, psycho-social, and territorial. Through wetting and scrubbing, threading and transferring, Ntlonti labours to aerially reveal (and conceal) a ‘body of land’ punctuated by marks, suggestive of violently whirling winds that rummage the surface. There is a productive tension between the scrubbed thin layer of painterly medium and the metaphorical heaviness of the blobs of thread that give the work a three-dimensionality. These strategies of peeling away and stitching evident in the artist’s cartographic forms, realised in what she calls “shy colours”1, earthy browns, pinks, dull whites and patches of blues, accentuate the sense of precarity and structural vulnerability so central in Ntlonti’s conceptual concerns.

A connection can be drawn between this precarity (that is as ontological as it is territorial) and what the artist calls “isingqala”2, a state of being that defies any easy definitional translation. This condition can be thought of as a deep sense of sorrow or the near-permanence of grief that grips and overwhelms the body. It is the vibrational and sonic properties of isingqala that could account for the tear in the land(scape), and the flesh, that has become a signature in the visual vocabulary of the artist. Isingqala signifies the afterlife of the catastrophe, the “paradigmatic origin” whose effect reverberates through our contemporary present. Ntlonti’s attention to the physicality of the Black domestic space that informs her choice of and approach to materials, in both its precarity and intramural (im)possibility, attests to the manner in which the violent tearing (of the flesh and land), constitutive of the anti-black modern order, and the repair-healing are concurrent modes of being in the world.

1 In a private conversation with the artist on the 26th May, 2023.

2 Also in a private conversation with the artist on the 26th May, 2023.

Works cited:

Abdur-Rahman, Aliyyah I., “Black Grotesquerie”, in American Literary History 0.0 (2017), 1-22.

Felstiner, John, Paul Celan: poet, survivor, Jew. New Haven and London: Yale University Press (1995).

Wilderson, Frank B. III, “Biko and the Problematic of Presence”, in Biko lives: Contesting the legacies of Steve Biko, ed. Andile Mngxitama, Amanda Alexander, and Nigel C. Gibson. New York: Palgrave Macmillan (2008), 95-114.

Wilderson, Frank B. III, Red, White and Black: Cinema and the structure of U.S Antagonisms. Durham & London: Duke university Press (2010).

Exhibition press:

Nkomo, V. Izonzobila: A tear in the world. Mail & Guardian, published 10 February 2024.

Text by Vusi Nkomo

There was earth inside them, and they dug.

— Paul Celan, Paul Celan: poet, survivor, Jew

. . .the sites and labors of loss might constitute. . .freedom’s proper domain (19)

— Aliyyah I. Abdur-Rahman, Black Grotesquerie

[W]e need a new language of abstraction to explain this horror.— Frank B.Wilderson, III, Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of U.S. Antagonisms

The profound stakes of Asemahle Ntlonti’s practice point to a symbiosis between a fundamental failure and a specific structure of domination that inaugurates our global modernity and anticipates our current catastrophe. For Ntlonti, the violence that founds this order lingers within the scars marking the surface of this land. This naked force, in Orlando Patterson’s words, is constitutively an “…ontological first moment—or a point of paradigmatic origin”, to borrow from theorist Frank Wilderson in his essay Biko and the Problematic of Presence (2008). Perhaps it is this prior-ness that perplexes: how can something so essential and foundational escape all the modes of inquiry that seek to render it conceptually coherent, that is, sayable and thinkable?

Ntlonti’s work, which spans across painting, performance, sculpture and sound, is preoccupied with structural impossibility and limit. What consistently appears as cracks in the composition, we might read as the woundedness of the ‘pained’ landscapes against the (im)possibility of repair. Ntlonti’s abstraction hints at the consistency in the violence of the structure that displaces, dislocates and dispossesses at all levels, including corporeal, political, spiritual, psycho-social, and territorial. Through wetting and scrubbing, threading and transferring, Ntlonti labours to aerially reveal (and conceal) a ‘body of land’ punctuated by marks, suggestive of violently whirling winds that rummage the surface. There is a productive tension between the scrubbed thin layer of painterly medium and the metaphorical heaviness of the blobs of thread that give the work a three-dimensionality. These strategies of peeling away and stitching evident in the artist’s cartographic forms, realised in what she calls “shy colours”1, earthy browns, pinks, dull whites and patches of blues, accentuate the sense of precarity and structural vulnerability so central in Ntlonti’s conceptual concerns.

A connection can be drawn between this precarity (that is as ontological as it is territorial) and what the artist calls “isingqala”2, a state of being that defies any easy definitional translation. This condition can be thought of as a deep sense of sorrow or the near-permanence of grief that grips and overwhelms the body. It is the vibrational and sonic properties of isingqala that could account for the tear in the land(scape), and the flesh, that has become a signature in the visual vocabulary of the artist. Isingqala signifies the afterlife of the catastrophe, the “paradigmatic origin” whose effect reverberates through our contemporary present. Ntlonti’s attention to the physicality of the Black domestic space that informs her choice of and approach to materials, in both its precarity and intramural (im)possibility, attests to the manner in which the violent tearing (of the flesh and land), constitutive of the anti-black modern order, and the repair-healing are concurrent modes of being in the world.

1 In a private conversation with the artist on the 26th May, 2023.

2 Also in a private conversation with the artist on the 26th May, 2023.

Works cited:

Abdur-Rahman, Aliyyah I., “Black Grotesquerie”, in American Literary History 0.0 (2017), 1-22.

Felstiner, John, Paul Celan: poet, survivor, Jew. New Haven and London: Yale University Press (1995).

Wilderson, Frank B. III, “Biko and the Problematic of Presence”, in Biko lives: Contesting the legacies of Steve Biko, ed. Andile Mngxitama, Amanda Alexander, and Nigel C. Gibson. New York: Palgrave Macmillan (2008), 95-114.

Wilderson, Frank B. III, Red, White and Black: Cinema and the structure of U.S Antagonisms. Durham & London: Duke university Press (2010).

Exhibition press:

Nkomo, V. Izonzobila: A tear in the world. Mail & Guardian, published 10 February 2024.

Experiencing the work of Senzeni Marasela and Asemahle Ntlonti means moving with it across numerous landscapes, timescapes, and memory worlds. This journey is circular, and the bodies of work relay to one another histories and stories from many places in different moments and yet, in many instances, they share their allusion to a pervasive darkness and a sense of loss.

Ijeremani Lam is a mixed-media show consisting of new works from Marasela’s ongoing project that tells stories of her alter-ego Theodorah, a woman named after and inspired by the artist’s mother, whilst Ntlonti’s Kukho Isililo Somntu II mixes the historical and autobiographical story of the violence of racialized oppression in the nation.

Theodorah, who lives in Mvenyane in rural Eastern Cape, longs across thousands of kilometres for her husband Gebane, who works in Johannesburg. Her longing is so great and her patience so tender that we forget that such things are the result of brutal and crass land division in the historical formation of an efficient migrant labour system, whose disregard for love is the cause of generations of heartbreak. It is within this South Africa – the one held too tight by its false borders and the one whose labour system continues to divide lovers – that the backdrop is formed to Theodorah’s pining over her dimming memory of Gebane.

Theodorah has ‘lived’ since 2003, and she will continue to do so, for her experience of having a family separated by a patriarchal and racist regime mirrors that of millions of black people within post-colonial Africa. Framing Theodorah as a performance therefore does not seem to aptly address the heaviness and the historical and contemporary reality of the space she occupies.

I am similarly reluctant to discuss Asemahle Ntlonti’s Amabali (2016) as simply an ‘artwork’. The familiar blue and yellow stripes of a SAPS police van are painted along the gallery wall. A number of barred metal windows fitted with speakers are mounted above, alluding to the back of the van, for arrested subjects. I am reluctant to engage with it exclusively as an artwork because the presence, and even the implied presence, of a police van triggers within so many black people panic, adrenaline, and perhaps most centrally, a sense of guilt. This is an internalised double consciousness, where we must always police ourselves in response to the various ways we know we might be framed as guilty, violent, or dangerous. In this sense the black subject both occupies the back of the van, and observes themselves in the back of the van, reminding us of the perpetual limbo state of TheodorahSenzeni, another ‘multiple-single’ subject who lives both inside and outside of her body.

So with Amabali, while it is about overt violence and brutality, it is as much about internalised violence and the notion of black life as social death1. And then, yes, it is about death – the violent and hateful death that black people experience far too often. Each window of the ‘van’ plays a different sound, and Ntlonti’s recital of Chris van Wyk’s In Detention2, the chaotic sounds of RhodesMustFall activists’ clashes with police, and early musings from her younger cousins (the next generation of fighters) mingle with one another into a collective voice of sorrow. Amabali mourns for our past, present, and future, outlining at once a personal, and collective relationship that black people have with police and with policing.

Perhaps it is this simultaneous relationship with the singular and the collective, the past, present and future, that makes the work of both artists – aesthetically so different – markedly historically relevant. There is little separation between either of the artists from their work, where Ntlonti meditates and moves amongst death, Theodorah acts as the vessel for the generational heartbreak and generational forgetting in Marasela’s family. Ntlonti’s Inhlangano (2016), an installation of colourful plastic plates marked with the family names of people who live close by in the Eastern Cape, refers again to death, to the borrowing of plates for funerals, to another action of living together, eating together – amongst lives passed on from here.

So throughout the exhibition, it might be easy to talk about a feeling of ‘black pain’ or loss – loss of lives, disintegrating memory, loss of land, humanity, time, love – but we would be mistaken to end there. Theodorah is not characterised by that which she does not have, but by her modes of owning. It is the way she owns her loss and sadness, the way she writes her own history and the understanding of her own imagination that makes her interesting. Ntlonti’s persistent presence within her work, even as it operates in the realm of death feels like an assertion of life itself, speaking against the racist notion of black people as a sum of their material means, or loss thereof.

Weaving their ways through necessary darknesses and joys Senzeni Marasela’s and Asemahle Ntlonti’s explorations of the history of violence, and histories of love, pack into the confines of the gallery an impossible timespan, and a landscape stretching from the Eastern Cape to Johannesburg.

Words by Thuli Gamedze

—

Senzeni Marasela was born in 1977 in Thokoza, South Africa. She studied at the University of the Witswaterstrand in Johannesburg, where she obtained a BA Fine Arts degree in 1998. Marasela has had seven solo exhibitions to date, most recently Sarah, Theodora and Senzeni in Johannesburg (Art On Paper, Johanensburg, 2011) and Beyond Booty: Covering Sarah Baartman and other Tales (Axis Gallery, New York, 2010). She has also participated in numerous local and international group exhibitions, among others, Africa: Raccontare un Mondo (PAC, Milan, 2017), KIN (HANGAR Centro de Investigação Artística, Lisbon, 2016) and Nomad Bodies (Royal Academy of Fine Art, Antwerp, 2014). Marasela was an artist-in-residence at the Iziko South African National Gallery in 2000, and in 2002 she was the recipient of the Thami Mnyele Scholarship. Her work has been collected by several prominent institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Marasela lives and works in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Asemahle Ntlonti was born in 1993 in Cape Town, South Africa. She graduated from the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art earlier this year, where she majored in sculpture. She was awarded Hoosein Mahomed Award for Excellence in 2015 and the Barbaro Fairhead award for social responsibility in 2014. Ntlonti was a top 10 finalist for Barclays L’Atelier 2016, participated in Infecting The City 2016 as well as a finalist for Sasol New Signatures, 2015. She is a member of iQhiya, a collective of 11 black women based in Cape Town, Johannesburg, South Africa and Botswana. iQhiya is currently participating in Documenta 14, 2017 and has exhibited and performed in various spaces. Ntlonti lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa.

Ijeremani Lam is a mixed-media show consisting of new works from Marasela’s ongoing project that tells stories of her alter-ego Theodorah, a woman named after and inspired by the artist’s mother, whilst Ntlonti’s Kukho Isililo Somntu II mixes the historical and autobiographical story of the violence of racialized oppression in the nation.

Theodorah, who lives in Mvenyane in rural Eastern Cape, longs across thousands of kilometres for her husband Gebane, who works in Johannesburg. Her longing is so great and her patience so tender that we forget that such things are the result of brutal and crass land division in the historical formation of an efficient migrant labour system, whose disregard for love is the cause of generations of heartbreak. It is within this South Africa – the one held too tight by its false borders and the one whose labour system continues to divide lovers – that the backdrop is formed to Theodorah’s pining over her dimming memory of Gebane.

Theodorah has ‘lived’ since 2003, and she will continue to do so, for her experience of having a family separated by a patriarchal and racist regime mirrors that of millions of black people within post-colonial Africa. Framing Theodorah as a performance therefore does not seem to aptly address the heaviness and the historical and contemporary reality of the space she occupies.

I am similarly reluctant to discuss Asemahle Ntlonti’s Amabali (2016) as simply an ‘artwork’. The familiar blue and yellow stripes of a SAPS police van are painted along the gallery wall. A number of barred metal windows fitted with speakers are mounted above, alluding to the back of the van, for arrested subjects. I am reluctant to engage with it exclusively as an artwork because the presence, and even the implied presence, of a police van triggers within so many black people panic, adrenaline, and perhaps most centrally, a sense of guilt. This is an internalised double consciousness, where we must always police ourselves in response to the various ways we know we might be framed as guilty, violent, or dangerous. In this sense the black subject both occupies the back of the van, and observes themselves in the back of the van, reminding us of the perpetual limbo state of TheodorahSenzeni, another ‘multiple-single’ subject who lives both inside and outside of her body.

So with Amabali, while it is about overt violence and brutality, it is as much about internalised violence and the notion of black life as social death1. And then, yes, it is about death – the violent and hateful death that black people experience far too often. Each window of the ‘van’ plays a different sound, and Ntlonti’s recital of Chris van Wyk’s In Detention2, the chaotic sounds of RhodesMustFall activists’ clashes with police, and early musings from her younger cousins (the next generation of fighters) mingle with one another into a collective voice of sorrow. Amabali mourns for our past, present, and future, outlining at once a personal, and collective relationship that black people have with police and with policing.

Perhaps it is this simultaneous relationship with the singular and the collective, the past, present and future, that makes the work of both artists – aesthetically so different – markedly historically relevant. There is little separation between either of the artists from their work, where Ntlonti meditates and moves amongst death, Theodorah acts as the vessel for the generational heartbreak and generational forgetting in Marasela’s family. Ntlonti’s Inhlangano (2016), an installation of colourful plastic plates marked with the family names of people who live close by in the Eastern Cape, refers again to death, to the borrowing of plates for funerals, to another action of living together, eating together – amongst lives passed on from here.

So throughout the exhibition, it might be easy to talk about a feeling of ‘black pain’ or loss – loss of lives, disintegrating memory, loss of land, humanity, time, love – but we would be mistaken to end there. Theodorah is not characterised by that which she does not have, but by her modes of owning. It is the way she owns her loss and sadness, the way she writes her own history and the understanding of her own imagination that makes her interesting. Ntlonti’s persistent presence within her work, even as it operates in the realm of death feels like an assertion of life itself, speaking against the racist notion of black people as a sum of their material means, or loss thereof.

Weaving their ways through necessary darknesses and joys Senzeni Marasela’s and Asemahle Ntlonti’s explorations of the history of violence, and histories of love, pack into the confines of the gallery an impossible timespan, and a landscape stretching from the Eastern Cape to Johannesburg.

1 - Social death, a term first used by Frank Wilderson, is a way to describe the mode of existence forced onto black people within a world Wilderson characterises as ‘anti-black’. In line with the Afropessimist school of thought, social death is characterised by the black subject’s vulnerability to gratuitous violence, their natal alienation, and dishonour experienced purely by virtue of their existence.

2 - In Detention, 1979 by Chris Van Wyk, is a poem that alludes with a scarce palette of words, to the brutal torture and murder at ‘John Vorster’ during apartheid.

Words by Thuli Gamedze

—

Senzeni Marasela was born in 1977 in Thokoza, South Africa. She studied at the University of the Witswaterstrand in Johannesburg, where she obtained a BA Fine Arts degree in 1998. Marasela has had seven solo exhibitions to date, most recently Sarah, Theodora and Senzeni in Johannesburg (Art On Paper, Johanensburg, 2011) and Beyond Booty: Covering Sarah Baartman and other Tales (Axis Gallery, New York, 2010). She has also participated in numerous local and international group exhibitions, among others, Africa: Raccontare un Mondo (PAC, Milan, 2017), KIN (HANGAR Centro de Investigação Artística, Lisbon, 2016) and Nomad Bodies (Royal Academy of Fine Art, Antwerp, 2014). Marasela was an artist-in-residence at the Iziko South African National Gallery in 2000, and in 2002 she was the recipient of the Thami Mnyele Scholarship. Her work has been collected by several prominent institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Marasela lives and works in Johannesburg, South Africa.

Asemahle Ntlonti was born in 1993 in Cape Town, South Africa. She graduated from the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art earlier this year, where she majored in sculpture. She was awarded Hoosein Mahomed Award for Excellence in 2015 and the Barbaro Fairhead award for social responsibility in 2014. Ntlonti was a top 10 finalist for Barclays L’Atelier 2016, participated in Infecting The City 2016 as well as a finalist for Sasol New Signatures, 2015. She is a member of iQhiya, a collective of 11 black women based in Cape Town, Johannesburg, South Africa and Botswana. iQhiya is currently participating in Documenta 14, 2017 and has exhibited and performed in various spaces. Ntlonti lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa.