the secret harpist

takes a cup, moves to the side.

kneels by the curbstone, with a mat. washes the area.

takes off his top. prepares a bed. drinks as much water as she can.

wonders about the weight of Sundays. why some days feel light.

collects bricks from the lake. at night the neighbor moves.

thinks he was in the sun for too long. a slight headache.

sits on the swing next door. counts trees.

talks to the tree feller in the morning.

sits by what is called the holy land, locked like a courtyard

between other buildings. spits on the ground. wonders about

the things that turn, moral law, celestial bodies,

bodies on the road.

watches the sun set earlier, a fast passage.

sees how they shore their hearts, in the room next door.

knows the length of a shoulder, how you hold yourself.

when asleep, small movements of two breaths.

holds council by the entrance. carries a sick bird, a human.

says I saw you before. says those

with their wishes on their sleeves, who leave early.

later, writes with charcoal on columns under the highway.

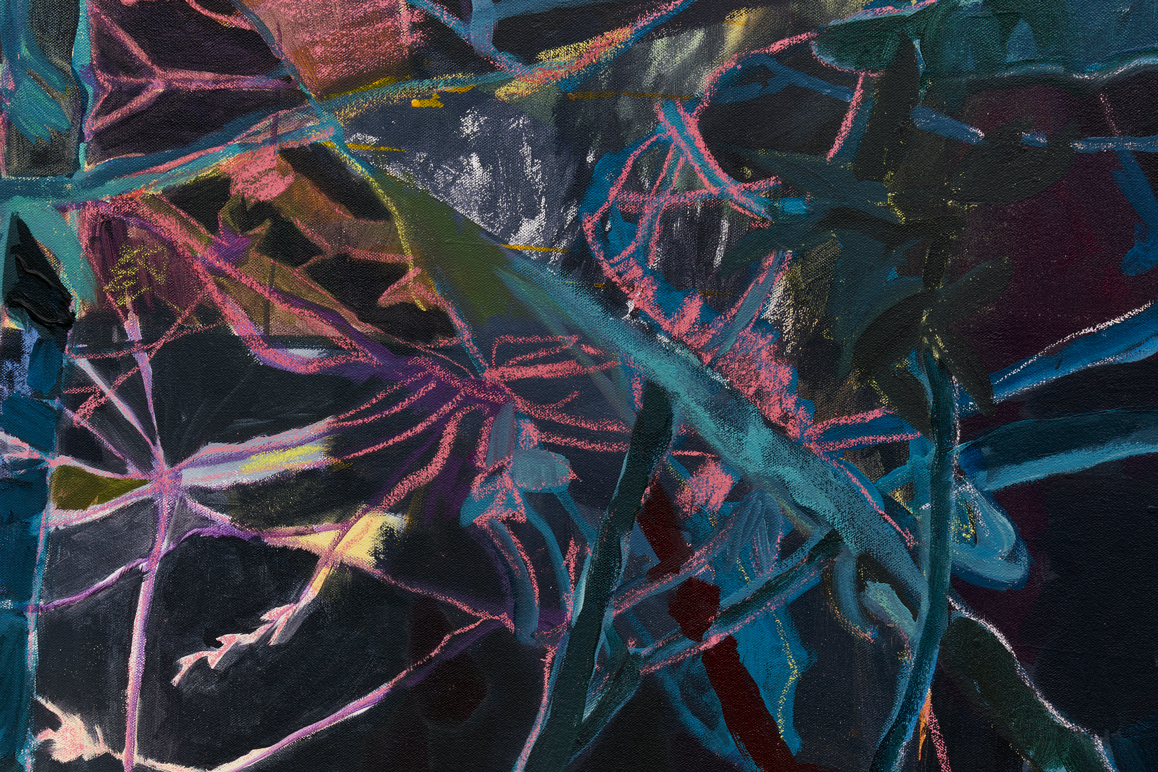

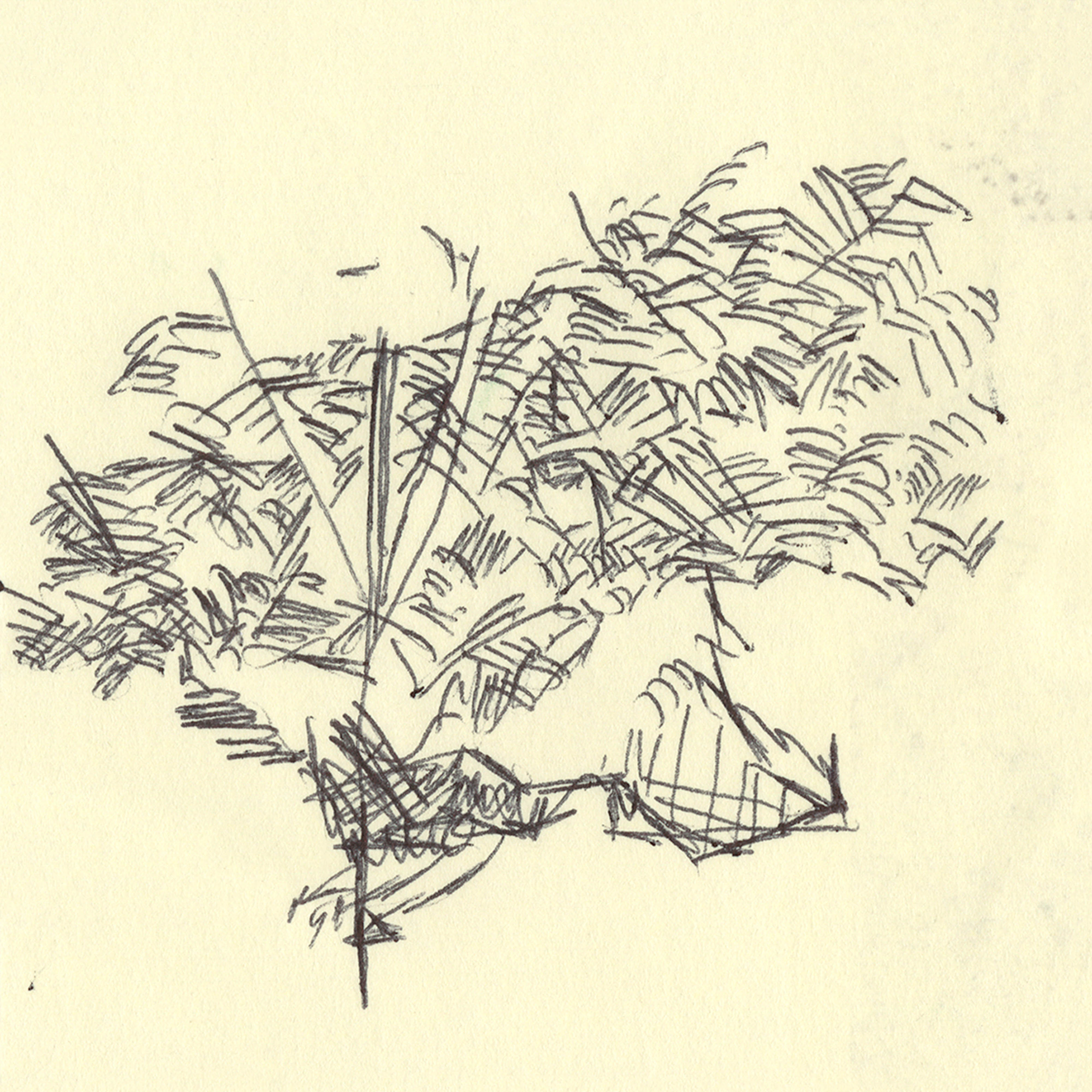

For the past three years Kreutzfeldt has been working on a series of paintings with the motif of a ‘night tree’. ‘They began as slow compositional improvisations on near square canvases, based on photographs of the same tree. The photographs were projected onto the surfaces, then traced, erased, re-projected and repainted. The size of the canvases are set by the height of standard doors, referencing how one enters or exits spaces, interiors and exteriors. With the repetition of the same motif, the paintings cite the location of a tree in a garden in Johannesburg, an actual place at different moments in time – and with it invoke the distinct coordinates of a place tied to its fraught heritage, daily intensities and sense of a precarious future. Daily rhythms were profoundly disrupted, as well as augmented, through the global pandemic and phases of lockdown.

Initially conceived of as formal studies, the paintings work the surface between perception and abstraction, the absence of horizon unsettling the idea of a rendered, known space. They propose visual inversions, forms emerging and receding into non-forms and densities; operating somewhere at the border of what is perceptible or not, the question of being in this world, edges of sanctity, sanity and illness. The paintings became a sideways mode of returning to the same image, working from lighter planes to darker shades, rendering branches and leaves into an exchange of spatial or bodily figures. Painting approached as a form of notetaking, the work evolved concurrent to the diarising of news, their partial histories, the emptying of streets at night, voices, the anatomy of vision out of place.’

To Pathik, who earlier this year sent me a playlist named ‘the secret harpist’.

—

Dorothee Kreutzfeldt (b.1970, Windhoek, Namibia) is based in Johannesburg. Her interest in urban structures and their embedded socio-political histories and imaginations have informed her paintings, research and collaborations over the last twenty years. The city of Johannesburg has played a central role in her life and work, and continues to anchor questions around how the city crafts, undermines and explodes the experiences of time, space and subjectivity. Previous solo shows include City without a sun (2018); Extensions to the Lot Line (2017); At Present, (2015); and The Immanent Inauguration of the 5th Corner (2010) at blank projects, and HERE WE (2016) at Room Gallery & Projects in Johannesburg. In 2013 she co-authored the book Not No Place, Johannesburg: Fragments of Spaces and Times with Bettina Malcomess. Concurrent to her artistic practice and travels, Kreutzfeldt lectures at the Wits School of Arts where she is working towards a PhD.

exhibition press:

Munnik, G. Wonders about the weight of Sundays: Dorothee Kreutzfeldt’s ‘the secret harpist’. Artthrob (published 15 November 2022)

takes a cup, moves to the side.

kneels by the curbstone, with a mat. washes the area.

takes off his top. prepares a bed. drinks as much water as she can.

wonders about the weight of Sundays. why some days feel light.

collects bricks from the lake. at night the neighbor moves.

thinks he was in the sun for too long. a slight headache.

sits on the swing next door. counts trees.

talks to the tree feller in the morning.

sits by what is called the holy land, locked like a courtyard

between other buildings. spits on the ground. wonders about

the things that turn, moral law, celestial bodies,

bodies on the road.

watches the sun set earlier, a fast passage.

sees how they shore their hearts, in the room next door.

knows the length of a shoulder, how you hold yourself.

when asleep, small movements of two breaths.

holds council by the entrance. carries a sick bird, a human.

says I saw you before. says those

with their wishes on their sleeves, who leave early.

later, writes with charcoal on columns under the highway.

For the past three years Kreutzfeldt has been working on a series of paintings with the motif of a ‘night tree’. ‘They began as slow compositional improvisations on near square canvases, based on photographs of the same tree. The photographs were projected onto the surfaces, then traced, erased, re-projected and repainted. The size of the canvases are set by the height of standard doors, referencing how one enters or exits spaces, interiors and exteriors. With the repetition of the same motif, the paintings cite the location of a tree in a garden in Johannesburg, an actual place at different moments in time – and with it invoke the distinct coordinates of a place tied to its fraught heritage, daily intensities and sense of a precarious future. Daily rhythms were profoundly disrupted, as well as augmented, through the global pandemic and phases of lockdown.

Initially conceived of as formal studies, the paintings work the surface between perception and abstraction, the absence of horizon unsettling the idea of a rendered, known space. They propose visual inversions, forms emerging and receding into non-forms and densities; operating somewhere at the border of what is perceptible or not, the question of being in this world, edges of sanctity, sanity and illness. The paintings became a sideways mode of returning to the same image, working from lighter planes to darker shades, rendering branches and leaves into an exchange of spatial or bodily figures. Painting approached as a form of notetaking, the work evolved concurrent to the diarising of news, their partial histories, the emptying of streets at night, voices, the anatomy of vision out of place.’

To Pathik, who earlier this year sent me a playlist named ‘the secret harpist’.

—

Dorothee Kreutzfeldt (b.1970, Windhoek, Namibia) is based in Johannesburg. Her interest in urban structures and their embedded socio-political histories and imaginations have informed her paintings, research and collaborations over the last twenty years. The city of Johannesburg has played a central role in her life and work, and continues to anchor questions around how the city crafts, undermines and explodes the experiences of time, space and subjectivity. Previous solo shows include City without a sun (2018); Extensions to the Lot Line (2017); At Present, (2015); and The Immanent Inauguration of the 5th Corner (2010) at blank projects, and HERE WE (2016) at Room Gallery & Projects in Johannesburg. In 2013 she co-authored the book Not No Place, Johannesburg: Fragments of Spaces and Times with Bettina Malcomess. Concurrent to her artistic practice and travels, Kreutzfeldt lectures at the Wits School of Arts where she is working towards a PhD.

exhibition press:

Munnik, G. Wonders about the weight of Sundays: Dorothee Kreutzfeldt’s ‘the secret harpist’. Artthrob (published 15 November 2022)

Walking the perimeter of what was the tent, it becomes increasingly hard to understand why it was so necessary to erect it. Was it because of these strange late summer rains, or maybe to block out the sun? I couldn’t imagine we could truly believe it would somehow summon a greater understanding of ourselves. It had no roof but a pitch, its brackets held back no water, only a faint set of unaccounted for events imprinted on the ground. We are left pulling up the floor together with the curtains. You kneel, you bow while I stare astonished; but you could now cross the lines to read this current moment better: How to enter the first heaven, which is this place, yet has traveled somewhere else.

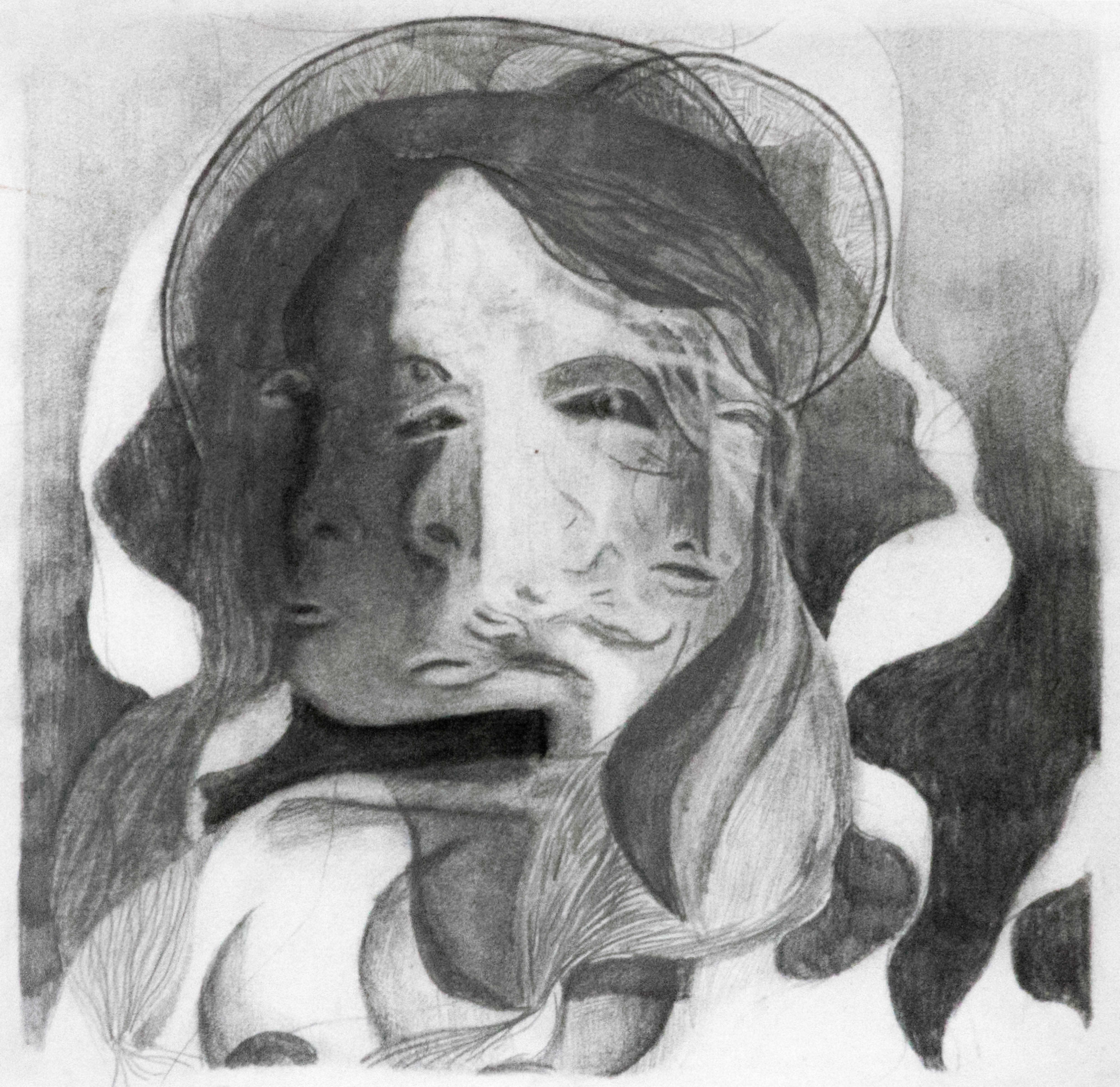

In this collaborative exhibition, Dorothee Kreutzfeldt and Blake Daniels present a new body of paintings, drawings and sculptural installations that reconstruct the intimate moments shared under a collapsing church tent outside their studio in Johannesburg. Each artist engages this collapsible and migratory border between what is holy and what is not, with a genuine pursuit of reconfiguring an undocumented history, each one out of sync with the each other. Kreutzfeldt works with the spatial association and structure of the tent, beginning with its movements, remnants and the ground it leaves behind. Daniels’s paintings tell stories of the tent; tales of murdered deities, sexual ceremony hidden from public view, or which a taboo love is drowned in baptism.

The title of the exhibition refers to the writings of Naguib Mahfouz in which he describes the space between earth and the heavens as a new city which is brilliantly illuminated, but without a sun. The City Without a Sun becomes a picture, an interior landscape, an old sticker pulled off the faded wall, in the shape of a tent. It is full of small moments and lesser events, often simple and benign, sometimes profound and marvellous.

—

Blake Daniels (b. 1990, Cincinnati, USA) is currently living and working between New York, USA and Johannesburg, ZA. He is the recipient of the Edward L. Ryerson Fellowship from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and received his Masters in Fine Arts through the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. His paintings visualize moments of intimacy with history, both lived and remembered, depicting bodies and landscapes which are constantly being altered, dislocated and fragmented through their internalization of the socially built histories they experience. Reconfiguring figure and ground relationships, Daniels weaves tales of love remembered and times forgotten, never allowing a definitive line to be establish between abstraction and figuration. Daniels was included in the critical survey 100 Painters of Tomorrow published through Thames & Hudson, and has exhibited internationally at Beers London, London, UK; Room, Johannesburg, ZA; Canwood Gallery, Herefordshire, UK; Sullivan Gallery, Chicago, USA; Monfai Arts Centre, Chiang Mai, THA; Fresh Exhibitions, Savannah, USA and Challery, Vienna, AUT.

Dorothee Kreutzfeldt (b.1970, Windhoek, Namibia) is based in Johannesburg. Her interest in urban structures and their embedded socio-political histories and imaginations have informed her paintings, research and collaborations over the last twenty years. The city of Johannesburg has played a central role in her life and work, and continues to anchor questions around how the city crafts, undermines and explodes the experiences of time, space and subjectivity. Previous solo shows include Extensions to the Lot Line (2017); At Present, (2015); and The Immanent Inauguration of the 5th Corner (2010) at blank projects, and HERE WE (2016) at Room Gallery & Projects in Johannesburg. In 2013 she co-authored the book Not No Place, Johannesburg: Fragments of Spaces and Times with Bettina Malcomess. Concurrent to her artistic practice and travels, Kreutzfeldt lectures at the Wits School of Arts where she is working towards a PhD.

In this collaborative exhibition, Dorothee Kreutzfeldt and Blake Daniels present a new body of paintings, drawings and sculptural installations that reconstruct the intimate moments shared under a collapsing church tent outside their studio in Johannesburg. Each artist engages this collapsible and migratory border between what is holy and what is not, with a genuine pursuit of reconfiguring an undocumented history, each one out of sync with the each other. Kreutzfeldt works with the spatial association and structure of the tent, beginning with its movements, remnants and the ground it leaves behind. Daniels’s paintings tell stories of the tent; tales of murdered deities, sexual ceremony hidden from public view, or which a taboo love is drowned in baptism.

The title of the exhibition refers to the writings of Naguib Mahfouz in which he describes the space between earth and the heavens as a new city which is brilliantly illuminated, but without a sun. The City Without a Sun becomes a picture, an interior landscape, an old sticker pulled off the faded wall, in the shape of a tent. It is full of small moments and lesser events, often simple and benign, sometimes profound and marvellous.

—

Blake Daniels (b. 1990, Cincinnati, USA) is currently living and working between New York, USA and Johannesburg, ZA. He is the recipient of the Edward L. Ryerson Fellowship from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and received his Masters in Fine Arts through the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. His paintings visualize moments of intimacy with history, both lived and remembered, depicting bodies and landscapes which are constantly being altered, dislocated and fragmented through their internalization of the socially built histories they experience. Reconfiguring figure and ground relationships, Daniels weaves tales of love remembered and times forgotten, never allowing a definitive line to be establish between abstraction and figuration. Daniels was included in the critical survey 100 Painters of Tomorrow published through Thames & Hudson, and has exhibited internationally at Beers London, London, UK; Room, Johannesburg, ZA; Canwood Gallery, Herefordshire, UK; Sullivan Gallery, Chicago, USA; Monfai Arts Centre, Chiang Mai, THA; Fresh Exhibitions, Savannah, USA and Challery, Vienna, AUT.

Dorothee Kreutzfeldt (b.1970, Windhoek, Namibia) is based in Johannesburg. Her interest in urban structures and their embedded socio-political histories and imaginations have informed her paintings, research and collaborations over the last twenty years. The city of Johannesburg has played a central role in her life and work, and continues to anchor questions around how the city crafts, undermines and explodes the experiences of time, space and subjectivity. Previous solo shows include Extensions to the Lot Line (2017); At Present, (2015); and The Immanent Inauguration of the 5th Corner (2010) at blank projects, and HERE WE (2016) at Room Gallery & Projects in Johannesburg. In 2013 she co-authored the book Not No Place, Johannesburg: Fragments of Spaces and Times with Bettina Malcomess. Concurrent to her artistic practice and travels, Kreutzfeldt lectures at the Wits School of Arts where she is working towards a PhD.

Reading up on how to measure vertical and horizontal distances on uneven terrain across obstacles reveals that flags make sightings (of pegged ground) easier. What distances do you cover in leaning back, and then in returning? Will you find the same room, place, chair? Or to put it differently, how far can you lean back in small increments, not as an exercise, but as a necessary means to recover and adjust your sightline to the given.

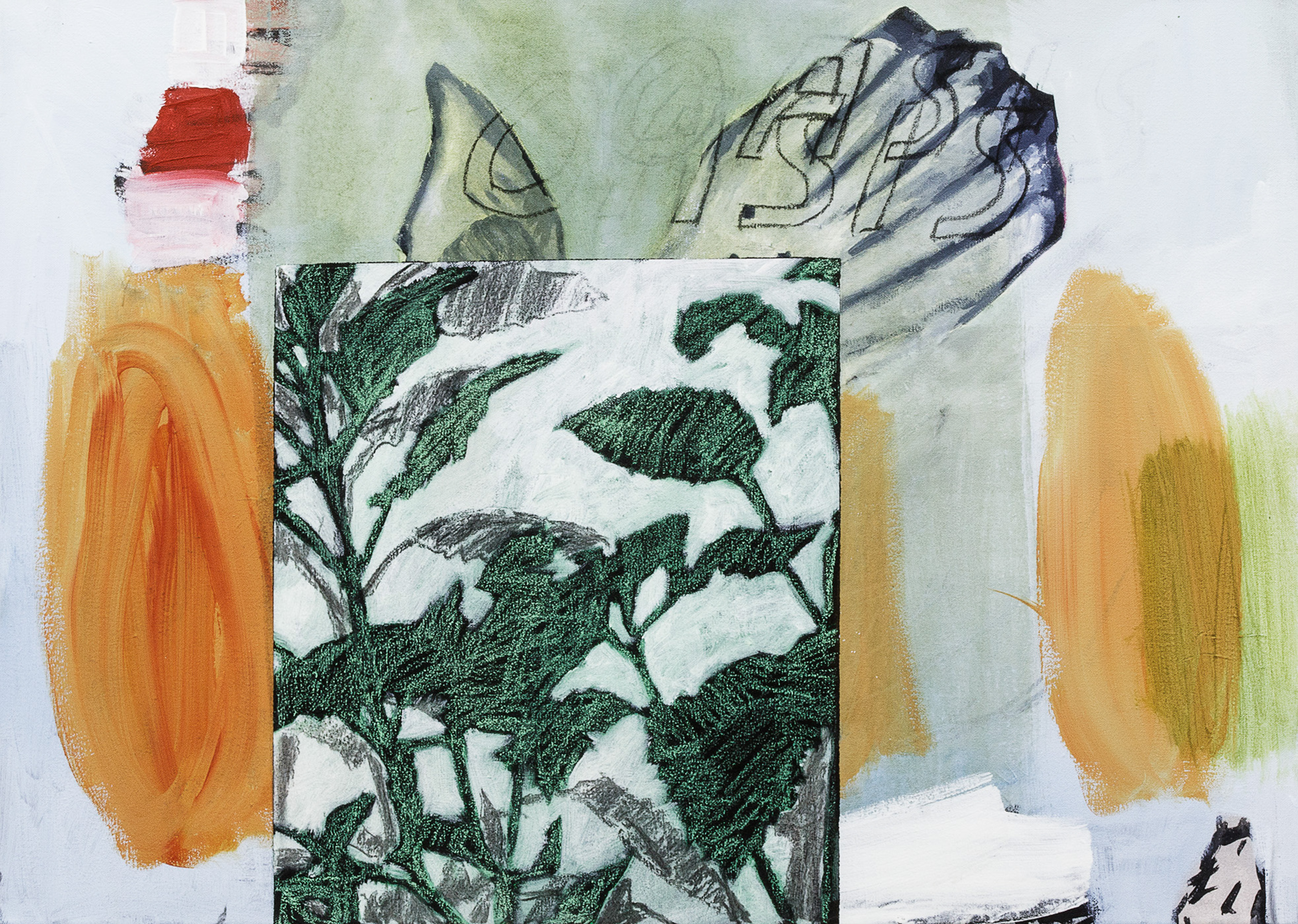

The paintings form an incoherent series of singular moments. They are informed by disparate sites in a lived environment, defined as a house, garden, vacant plot or a suburb, here “mixed income”, there “informal” or “regenerated”. If a site can be understood as the result of a project, or of a series of events and experiences, the paintings are cued by their incidental formations or topologies which invite analysis of the spaces we inhabit that feel continuously unsettled, and policed. How much then are we shaped internally by what is built and adhere to the social contract that calls us citizens and co-habitants?

An advert at the Cape Town airport proclaims the country as ‘the cradle of formal mining’. A shop on Albertina Sisulu is named ‘heaven is a reality’. A small table lies on its side on the pavement up the road. You place a mat at the entrance of your house that reads ‘welcome’. Strategies of ‘win and lose’ are debated on the radio. The seeds you bargained for “may have been chemically treated”. To break the granite you first make a fire on the surface, then you pour cold water. Each instance contains decisions, intimacies and narratives that reveal injunctions in history and the everyday, and speak to how distances and proximities are learned, towards a point in the near future. In leaning back, the lot line curves.1

* Lot line: boundary line of a parcel of land

—

blank is pleased to present EXTENSIONS TO THE LOT LINE by Dorothee Kreutzfeldt. Incorporating installation and wall paintings in addition to paintings on canvas, the exhibition is a continuation of Kreutzfeldt’s cross-disciplinary practice and artistic engagement with the urban landscape. The city of Johannesburg and its socio-politically constructed histories and spaces have been central to her work over the last 16 years. Her interests lie in how the city continues to craft, shift and explode the experience of time, place and subjectivity.

The paintings form an incoherent series of singular moments. They are informed by disparate sites in a lived environment, defined as a house, garden, vacant plot or a suburb, here “mixed income”, there “informal” or “regenerated”. If a site can be understood as the result of a project, or of a series of events and experiences, the paintings are cued by their incidental formations or topologies which invite analysis of the spaces we inhabit that feel continuously unsettled, and policed. How much then are we shaped internally by what is built and adhere to the social contract that calls us citizens and co-habitants?

An advert at the Cape Town airport proclaims the country as ‘the cradle of formal mining’. A shop on Albertina Sisulu is named ‘heaven is a reality’. A small table lies on its side on the pavement up the road. You place a mat at the entrance of your house that reads ‘welcome’. Strategies of ‘win and lose’ are debated on the radio. The seeds you bargained for “may have been chemically treated”. To break the granite you first make a fire on the surface, then you pour cold water. Each instance contains decisions, intimacies and narratives that reveal injunctions in history and the everyday, and speak to how distances and proximities are learned, towards a point in the near future. In leaning back, the lot line curves.1

* Lot line: boundary line of a parcel of land

—

blank is pleased to present EXTENSIONS TO THE LOT LINE by Dorothee Kreutzfeldt. Incorporating installation and wall paintings in addition to paintings on canvas, the exhibition is a continuation of Kreutzfeldt’s cross-disciplinary practice and artistic engagement with the urban landscape. The city of Johannesburg and its socio-politically constructed histories and spaces have been central to her work over the last 16 years. Her interests lie in how the city continues to craft, shift and explode the experience of time, place and subjectivity.

A series of paintings by Dorothee Kreutzfeldt

with contributions by Pamella Dlungwana and Ashley Walters

Situation 1: The room you are assigned is large. It has an interleading door and a main door. The furniture is plain and ordered along the longer wall. People come and go. There are many other rooms attached to this one, or it seems to be connected to other rooms in a significant way. It takes you a long time to find your way back to the entrance, which you recognise because of the portraits (like ancient brothers). The entrance does not allow a view into the interior. Reverse.

I imagine the reverse movement to be very slow, as if to extend and alter ‘Situation 1’, which is based on an existing building presently in use. Movements in reverse can be awkard, illogical actions, interesting to watch. They could be seen as a defensive, pathetic approach towards the present moment, as if moving with the back towards the observer, testing the degree of preparedness and a desire for the present to remain intact, to prolong. Of course the present cannot be in reverse mode; images and paintings however lend themselves easily towards the reverse (mirror image, blank reverse, the beginning of an image…). In film, the demolished wall magically rebuilds itself, a very simple ‘act’. (The reverse also defines a football tactic -‘a play on offense in which one back running laterally hands the ball to another back who is running in the opposite direction and who then makes either an end run or a cutback.’).

The set of paintings and their motifs – pre-cast cement eagle, carpet, trees etc. – propose a scenario or situation ‘at present’. Each work refers to a specific experience, a space, found film still or constructed photograph. The same motif re-appears in some paintings; a kind of self-repeat, or one that reverses/anticipates another image.

Photographer Ashley Walters and writer/cultural practitioner Pamella Dlungwana have contributed their own texts to the exhibition, which present additional situations in themselves.

—

Dorothee Kreutzfeldt (b1970) lives and works in Johannesburg where she lectures at the Wits School of Arts. Her practice involves painting and collaborations, often across different media and disciplines and with a strong interest in urban space and it’s contradictions, ironies and socio-political complexities. In 2013, Kreutzfeldt published ‘Not No Place. Johannesburg – Fragments of Spaces and Times’ in collaboration with Bettina Malcomess, a five-year book project that extended into workshops, conferences, presentations and exhibitions in different forms at Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, La Maison Rouge Paris, Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau Dresden, Goethe on Main Johannesburg and ISA Congress of Sociology Yokohama. She has participated in numerous exhibitions and residences, both nationally and internationally, since 1996. Her work is represented in a number of private and public collections, including the South African National Gallery and Johannesburg Art Gallery. Kreutzfeldt’s last solo exhibition, ‘The Imminent Inauguration of the 5th Corner’, was held at blank projects in 2010.

Ashley Walters (b1983) works mainly in photography and video. Based in Cape Town where he was born, he completed his Master of Fine Arts in 2013 at the Michaelis School of Fine Art and received the Tierney Fellowship in 2013/14. Walter’s photographic practice presents a subjective and critical approach to the complex behaviors and processes of urban life in Cape Town and its peripheries. His latest exhibition, ‘Uitsig’, explores notions of ‘community’ as lived, spatial and social construct, in which photography is approached as a participatory process.

Pamella Dlungwana is a Cape Town-based poet, writer, researcher and currently the regional coordinator of VANSA in the Western Cape. As coordinator/contributor she has worked with several publications and institutions including Chimurenga Magazine and The Chinua Achebe Centre. As poet and writer Dlungwana has collaborated with artists and performers, including Bandile Gumbi (‘No holy cows’), Francis Burger (‘Unlearning, names not signs not names’), Zanele Muholi (‘What do you see when you look at us?’), Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokghoto (‘Corner Loving’).

with contributions by Pamella Dlungwana and Ashley Walters

Situation 1: The room you are assigned is large. It has an interleading door and a main door. The furniture is plain and ordered along the longer wall. People come and go. There are many other rooms attached to this one, or it seems to be connected to other rooms in a significant way. It takes you a long time to find your way back to the entrance, which you recognise because of the portraits (like ancient brothers). The entrance does not allow a view into the interior. Reverse.

I imagine the reverse movement to be very slow, as if to extend and alter ‘Situation 1’, which is based on an existing building presently in use. Movements in reverse can be awkard, illogical actions, interesting to watch. They could be seen as a defensive, pathetic approach towards the present moment, as if moving with the back towards the observer, testing the degree of preparedness and a desire for the present to remain intact, to prolong. Of course the present cannot be in reverse mode; images and paintings however lend themselves easily towards the reverse (mirror image, blank reverse, the beginning of an image…). In film, the demolished wall magically rebuilds itself, a very simple ‘act’. (The reverse also defines a football tactic -‘a play on offense in which one back running laterally hands the ball to another back who is running in the opposite direction and who then makes either an end run or a cutback.’).

The set of paintings and their motifs – pre-cast cement eagle, carpet, trees etc. – propose a scenario or situation ‘at present’. Each work refers to a specific experience, a space, found film still or constructed photograph. The same motif re-appears in some paintings; a kind of self-repeat, or one that reverses/anticipates another image.

Photographer Ashley Walters and writer/cultural practitioner Pamella Dlungwana have contributed their own texts to the exhibition, which present additional situations in themselves.

—

Dorothee Kreutzfeldt (b1970) lives and works in Johannesburg where she lectures at the Wits School of Arts. Her practice involves painting and collaborations, often across different media and disciplines and with a strong interest in urban space and it’s contradictions, ironies and socio-political complexities. In 2013, Kreutzfeldt published ‘Not No Place. Johannesburg – Fragments of Spaces and Times’ in collaboration with Bettina Malcomess, a five-year book project that extended into workshops, conferences, presentations and exhibitions in different forms at Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research, La Maison Rouge Paris, Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau Dresden, Goethe on Main Johannesburg and ISA Congress of Sociology Yokohama. She has participated in numerous exhibitions and residences, both nationally and internationally, since 1996. Her work is represented in a number of private and public collections, including the South African National Gallery and Johannesburg Art Gallery. Kreutzfeldt’s last solo exhibition, ‘The Imminent Inauguration of the 5th Corner’, was held at blank projects in 2010.

Ashley Walters (b1983) works mainly in photography and video. Based in Cape Town where he was born, he completed his Master of Fine Arts in 2013 at the Michaelis School of Fine Art and received the Tierney Fellowship in 2013/14. Walter’s photographic practice presents a subjective and critical approach to the complex behaviors and processes of urban life in Cape Town and its peripheries. His latest exhibition, ‘Uitsig’, explores notions of ‘community’ as lived, spatial and social construct, in which photography is approached as a participatory process.

Pamella Dlungwana is a Cape Town-based poet, writer, researcher and currently the regional coordinator of VANSA in the Western Cape. As coordinator/contributor she has worked with several publications and institutions including Chimurenga Magazine and The Chinua Achebe Centre. As poet and writer Dlungwana has collaborated with artists and performers, including Bandile Gumbi (‘No holy cows’), Francis Burger (‘Unlearning, names not signs not names’), Zanele Muholi (‘What do you see when you look at us?’), Molemo Moiloa and Nare Mokghoto (‘Corner Loving’).

Reading up on how to measure vertical and horizontal distances on uneven terrain across obstacles reveals that flags make sightings (of pegged ground) easier. What distances do you cover in leaning back, and then in returning? Will you find the same room, place, chair? Or to put it differently, how far can you lean back in small increments, not as an exercise, but as a necessary means to recover and adjust your sightline to the given.

The paintings form an incoherent series of singular moments. They are informed by disparate sites in a lived environment, defined as a house, garden, vacant plot or a suburb, here “mixed income”, there “informal” or “regenerated”. If a site can be understood as the result of a project, or of a series of events and experiences, the paintings are cued by their incidental formations or topologies which invite analysis of the spaces we inhabit that feel continuously unsettled, and policed. How much then are we shaped internally by what is built and adhere to the social contract that calls us citizens and co-habitants?

An advert at the Cape Town airport proclaims the country as ‘the cradle of formal mining’. A shop on Albertina Sisulu is named ‘heaven is a reality’. A small table lies on its side on the pavement up the road. You place a mat at the entrance of your house that reads ‘welcome’. Strategies of ‘win and lose’ are debated on the radio. The seeds you bargained for “may have been chemically treated”. To break the granite you first make a fire on the surface, then you pour cold water. Each instance contains decisions, intimacies and narratives that reveal injunctions in history and the everyday, and speak to how distances and proximities are learned, towards a point in the near future. In leaning back, the lot line curves.1

* Lot line: boundary line of a parcel of land

—

blank is pleased to present EXTENSIONS TO THE LOT LINE by Dorothee Kreutzfeldt. Incorporating installation and wall paintings in addition to paintings on canvas, the exhibition is a continuation of Kreutzfeldt’s cross-disciplinary practice and artistic engagement with the urban landscape. The city of Johannesburg and its socio-politically constructed histories and spaces have been central to her work over the last 16 years. Her interests lie in how the city continues to craft, shift and explode the experience of time, place and subjectivity.

The paintings form an incoherent series of singular moments. They are informed by disparate sites in a lived environment, defined as a house, garden, vacant plot or a suburb, here “mixed income”, there “informal” or “regenerated”. If a site can be understood as the result of a project, or of a series of events and experiences, the paintings are cued by their incidental formations or topologies which invite analysis of the spaces we inhabit that feel continuously unsettled, and policed. How much then are we shaped internally by what is built and adhere to the social contract that calls us citizens and co-habitants?

An advert at the Cape Town airport proclaims the country as ‘the cradle of formal mining’. A shop on Albertina Sisulu is named ‘heaven is a reality’. A small table lies on its side on the pavement up the road. You place a mat at the entrance of your house that reads ‘welcome’. Strategies of ‘win and lose’ are debated on the radio. The seeds you bargained for “may have been chemically treated”. To break the granite you first make a fire on the surface, then you pour cold water. Each instance contains decisions, intimacies and narratives that reveal injunctions in history and the everyday, and speak to how distances and proximities are learned, towards a point in the near future. In leaning back, the lot line curves.1

* Lot line: boundary line of a parcel of land

—

blank is pleased to present EXTENSIONS TO THE LOT LINE by Dorothee Kreutzfeldt. Incorporating installation and wall paintings in addition to paintings on canvas, the exhibition is a continuation of Kreutzfeldt’s cross-disciplinary practice and artistic engagement with the urban landscape. The city of Johannesburg and its socio-politically constructed histories and spaces have been central to her work over the last 16 years. Her interests lie in how the city continues to craft, shift and explode the experience of time, place and subjectivity.