What is “postcolonial”? It seems to mean so much and nothing all at once. There is an entire field of creative and critical cultural production that is deeme “postcolonial”. It has become the label of a body of scholarship that includes work on the Raj in India, customary law in Africa, and Irish nationalism. For some it signifies the end of formal colonial rule and the founding of new nations. For others it represents liminal spaces, where innocence and trauma are neighbors. Still there’s an incompleteness to it. A limit to what it can hold of the time and space it wefts together; our now. It is a state of perpetua abeyance. There is no new place at which we may arrive; there is only post-colonial. It is a state of absence.

Our imaginations are engineered through ships, trade routes, beads, cotton, spices, crimes, hate, desperation, faith, conscription, wonder, science. What might a synonym be for such a word, “postcolonial”? Must it come from science or could it be something as elementary as food?

Where I come from we have a soup, callaloo. Often it serves as a sauce. We could call it postcolonial. It is made up of the leaves of the dasheen, okra, pumpkin, coconut milk, and salted pig meat or crab from the sea. The dasheen bush and okra probably came from West Africa. Coconuts arrived in the region around 1750. Salted pigmeat was from the Spanish; it could last well after the pig had been slaughtered, so proved a cheap source of protein for slave labour. A slave food. A poor person’s food. It is now integral to a national cuisine.

So, what is “postcolonial”? What is a white cloth wrapped around a Xhosa body? What is a rocket on the verge of flight? Modern, primitive; what do such words mean in the heat of the Algerian Revolution? Neither can encompass the pain and rage of Chinua Achebe on the heels of realizing it was he who was meant by “the horror, the horror”. Incomplete, yet brimming.

Half-Devil and Half-Child is an exhibition featuring the works of four artists exploring Colonialism and Postcolonialism in their practice. The title is extracted from the first stanza in Rudyard Kipling’s poem, ‘The White Man’s Burden’, first published in 1889.

Andrew Gilbert, a Scottish artist living and working in Berlin, is gaining increasing acclaim for his work focusing on Colonial history. He will be presenting four works on paper, and creating a dioramic installation in the gallery space.

“It is from the blood and guts and excrement of history that the works of Andrew Gilbert emerge. He wanders the plains of unspeakable violence, the scorched earth of wars fought in the name of Emperor, Queen, God and country. He notes the dismembered masses and the faceless collateral in the march to civilization and enlightenment. He remembers what the custodians of history have conveniently forgotten, erased, rewrote, tweaked and misrepresented. His oeuvre is a fucked up History Painting. He creates diabolical dioramas for ethnographic and military museums that unfortunately can never exist.”

Michael MacGarry presents four works in the exhibition. In Still Life, an assembled collection of 48 coconut-based products are arranged and styled as a classic 1980s product pack-shot, presented as a large format photograph. The Battle of Algiers employs the formal device of overlaying two video channels over one another. The forward film (green channel) plays normally as originall made, whilst the backward film (red channel) is played in reverse over each other. Both audio channels are left intact and play over and with one another. ‘The Battle of Algiers’ is a 1966 war film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, based on occurrences during the Algerian War (1954–62) against the French Government in North Africa. The film focuses on the years between 1954 and 1957 when guerrilla fighters regrouped and expanded, only to face a systematic attempt by French paratroopers to wipe them out. The film was banned for five years in France, where it was released cut in 1974.More recently the Pentagon has used the film as a key text in the analysis of urban conflict within the context of the 2nd Iraqi War.

Turiya Magadlela presents new work from her series titled Kaffersheet; a colloquial name denoting industrial cotton sold in fabric shops and prevalent in state institutions. Together with correctional services sheeting, this traditional isiXhosa cloth is stitched and creased into wall panels that are fraught with notions of incarceration in our society - past and present - and comment on larger relationships around trade, and notions of authenticity.

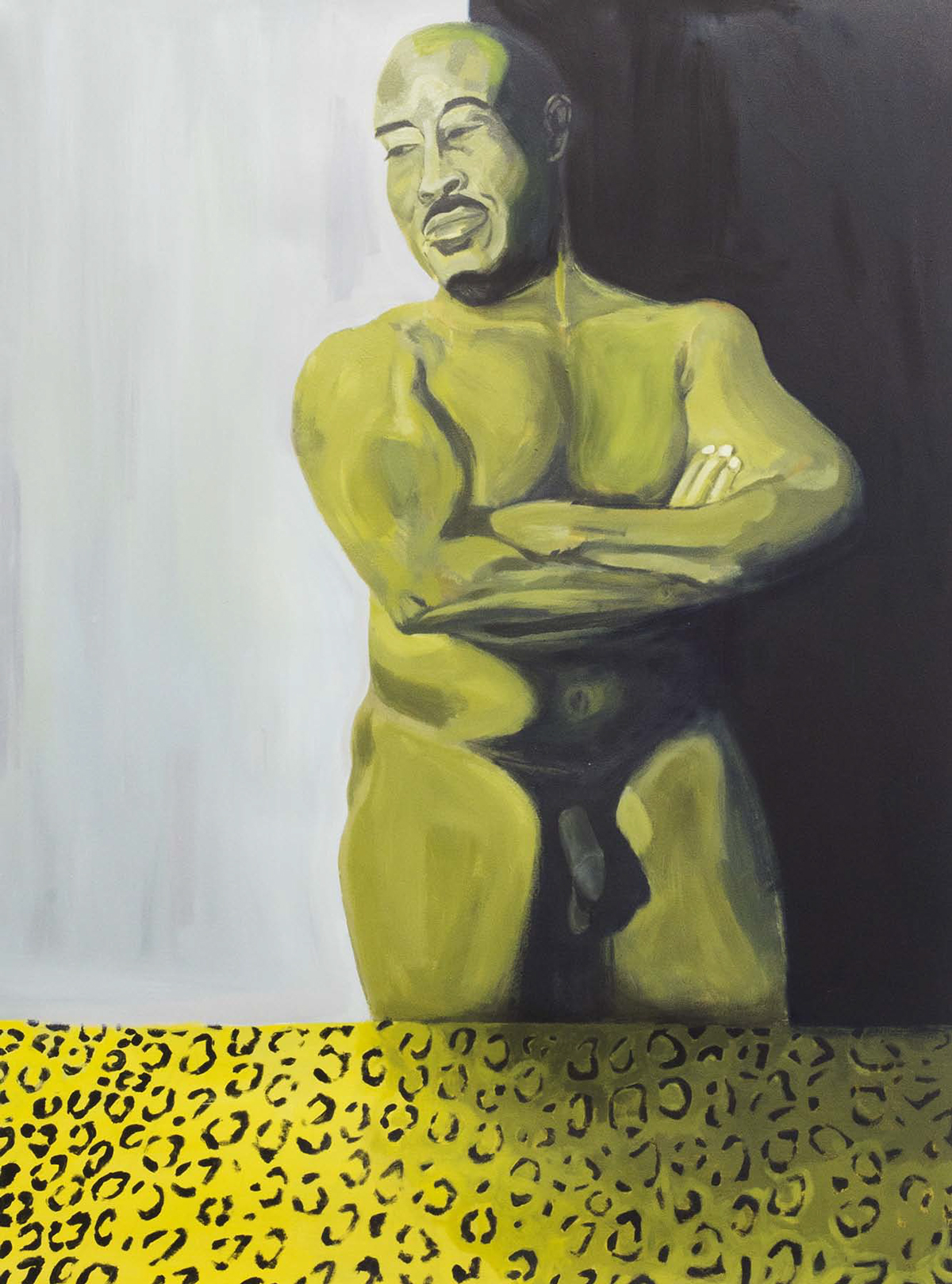

Six paintings by Thembalakhe Prospect Shibase cover a variety of sub-themes under the topic of Postcoloniality. Through these works he grapples with the cultural consequences of living in a former colony (and a new democracy, following almost half a century of Apartheid rule). In the artist’s own words, “from a perspective of a black man I look at the result of the catastrophic collision between western civilization and the indigenous African ‘primitive’ world. In that regard I try, through my work, to visually unpack both the overt and subtle complexities of life in the post-colony. The most dominant narrative of such life often presents itself in the form of an array of contradictions between African modernity, on the one hand, and primitiveness on the other. Religion, governance, culture, etc. are some of the areas in which the contradiction between modernity and primitiveness is mostly lived, especially by the former oppressed. While most of these contradictions manifest themselves in our material culture, in essence the point to the constantly shifting psychological state of being of the former oppressed (and to some extent that, too, of the former oppressor).”

Our imaginations are engineered through ships, trade routes, beads, cotton, spices, crimes, hate, desperation, faith, conscription, wonder, science. What might a synonym be for such a word, “postcolonial”? Must it come from science or could it be something as elementary as food?

Where I come from we have a soup, callaloo. Often it serves as a sauce. We could call it postcolonial. It is made up of the leaves of the dasheen, okra, pumpkin, coconut milk, and salted pig meat or crab from the sea. The dasheen bush and okra probably came from West Africa. Coconuts arrived in the region around 1750. Salted pigmeat was from the Spanish; it could last well after the pig had been slaughtered, so proved a cheap source of protein for slave labour. A slave food. A poor person’s food. It is now integral to a national cuisine.

So, what is “postcolonial”? What is a white cloth wrapped around a Xhosa body? What is a rocket on the verge of flight? Modern, primitive; what do such words mean in the heat of the Algerian Revolution? Neither can encompass the pain and rage of Chinua Achebe on the heels of realizing it was he who was meant by “the horror, the horror”. Incomplete, yet brimming.

- Victoria Collis-Buthelezi, 2014

Half-Devil and Half-Child is an exhibition featuring the works of four artists exploring Colonialism and Postcolonialism in their practice. The title is extracted from the first stanza in Rudyard Kipling’s poem, ‘The White Man’s Burden’, first published in 1889.

Take up the White Man’s burden, Send forth the best ye breed

Go bind your sons to exile To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness, On fluttered folk and wild--

Your new-caught, sullen peoples, Half-devil and half-child.

Go bind your sons to exile To serve your captives’ need;

To wait in heavy harness, On fluttered folk and wild--

Your new-caught, sullen peoples, Half-devil and half-child.

Andrew Gilbert, a Scottish artist living and working in Berlin, is gaining increasing acclaim for his work focusing on Colonial history. He will be presenting four works on paper, and creating a dioramic installation in the gallery space.

“It is from the blood and guts and excrement of history that the works of Andrew Gilbert emerge. He wanders the plains of unspeakable violence, the scorched earth of wars fought in the name of Emperor, Queen, God and country. He notes the dismembered masses and the faceless collateral in the march to civilization and enlightenment. He remembers what the custodians of history have conveniently forgotten, erased, rewrote, tweaked and misrepresented. His oeuvre is a fucked up History Painting. He creates diabolical dioramas for ethnographic and military museums that unfortunately can never exist.”

- Storm Janse van Rensburg

Michael MacGarry presents four works in the exhibition. In Still Life, an assembled collection of 48 coconut-based products are arranged and styled as a classic 1980s product pack-shot, presented as a large format photograph. The Battle of Algiers employs the formal device of overlaying two video channels over one another. The forward film (green channel) plays normally as originall made, whilst the backward film (red channel) is played in reverse over each other. Both audio channels are left intact and play over and with one another. ‘The Battle of Algiers’ is a 1966 war film directed by Gillo Pontecorvo, based on occurrences during the Algerian War (1954–62) against the French Government in North Africa. The film focuses on the years between 1954 and 1957 when guerrilla fighters regrouped and expanded, only to face a systematic attempt by French paratroopers to wipe them out. The film was banned for five years in France, where it was released cut in 1974.More recently the Pentagon has used the film as a key text in the analysis of urban conflict within the context of the 2nd Iraqi War.

Turiya Magadlela presents new work from her series titled Kaffersheet; a colloquial name denoting industrial cotton sold in fabric shops and prevalent in state institutions. Together with correctional services sheeting, this traditional isiXhosa cloth is stitched and creased into wall panels that are fraught with notions of incarceration in our society - past and present - and comment on larger relationships around trade, and notions of authenticity.

Six paintings by Thembalakhe Prospect Shibase cover a variety of sub-themes under the topic of Postcoloniality. Through these works he grapples with the cultural consequences of living in a former colony (and a new democracy, following almost half a century of Apartheid rule). In the artist’s own words, “from a perspective of a black man I look at the result of the catastrophic collision between western civilization and the indigenous African ‘primitive’ world. In that regard I try, through my work, to visually unpack both the overt and subtle complexities of life in the post-colony. The most dominant narrative of such life often presents itself in the form of an array of contradictions between African modernity, on the one hand, and primitiveness on the other. Religion, governance, culture, etc. are some of the areas in which the contradiction between modernity and primitiveness is mostly lived, especially by the former oppressed. While most of these contradictions manifest themselves in our material culture, in essence the point to the constantly shifting psychological state of being of the former oppressed (and to some extent that, too, of the former oppressor).”