Portrait by DNA photographers | Courtesy of the artist

Working in a variety of media that includes sculpture, installation, drawing and performance, Kemang Wa Lehulere uses found objects and salvaged materials to create environments and events that situate personal memories within, and in contrast to, collective narratives. Using conceptually loaded materials such as school desks, tyres, chalkboards and ceramic dogs, he poeticises the ‘double lives’ of objects - their potential for multiple interpretations - to tease out their ambivalent or subversive meanings through reconfiguration and assemblage.

In an attempt to comprehend and process the trauma of South Africa’s contemporary history(s), his practice combines physical acts of excavation and deconstruction with strategies of collaboration across time - be it through referencing, re-framing or ‘call-and-response’ - with artists, writers and family members of personal significance. By re-presenting in his exhibitions the work of other practitioners, whose contributions are often only posthumously acclaimed, Wa Lehulere points to the politics of cultural erasure and asks us to consider the gap between individual (complex, lived) experience and official (sanctioned, reductive) accounts of history. Dealing in the visual language of institutions, Wa Lehulere’s work contributes to the discourse around structural violence and the urgency of decolonised education and theoretical research.

To date, Wa Lehulere has had solo exhibitions at Göteborg Konsthall, Sweden (2021); Manchester International Festival, UK (2021); Tate Modern, UK (2019); Pasquart Art Centre, Switzerland (2018); MAXXI, Italy (2017); the Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Germany (2017); the Art Institute of Chicago, USA (2016); Gasworks, UK (2015); as well as blank projects (2025; 2023); Galerie Tschudi (2023; 2020); Marian Goodman Gallery (2018); and Stevenson (2018; 2016; 2015; 2012).

Selected group exhibitions include The Children are Now, at Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh (2025), Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics at LACMA, Los Angeles (2024), How Language Invents the World at Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur (2024), Long-distance Friendships at the14th Kaunas Biennial, Kaunas (2023), Beyond the Surface: Collage, Mixed Media and Textile Works from the Collection at Nasher Museum of Art, Durham (2022), The Future is Behind Us at A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town (2022), Stories of Resistance at Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis (2021), Global(e) Resistance at Centre Pompidou, Paris (2020), Beyond the Black Atlantic at Kunstverein Hannover (2020), Ernest Mancoba: I Shall Dance in a Different Society at Centre Pompidou, Paris (2019), May You Live in Interesting Times, the 58th Venice Biennale (2019), Leaving the Echo Chamber, 14th Sharjah Biennale (2019); O Triângulo Atlântico, 11th Mercosul Biennial (2018); More For Less at A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town (2018); Tell Freedom. 15 South African Artists at Kunsthal KAdE, Amersfoort (2018); Performa 17, New York (2017); Art/ Afrique, le nouvel atelier at Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris (2017); African Odysseys at Le Brass Cultural Centre of Forest, Belgium (2015); the 8th Berlin Biennale (2014); Public Intimacy: Art and Other Ordinary Acts in South Africa at Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco (2014); The Ungovernables, the 2nd New Museum Triennial, New York (2012); A Terrible Beauty is Born, the 11th Lyon Biennale (2011) and When Your Lips Are My Ears, Our Bodies Become Radios at Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern (2010).

Wa Lehulere was a co-founder of Gugulective (2006), an artist-led collective based in Cape Town, and a founding member of the Center for Historical Reenactments (2010) in Johannesburg. He was the winner of the inaugural Spier Contemporary Award in 2007, the MTN New Contemporaries Award in 2010, and the Tollman Award for the Visual Arts in 2012; he was one of two young artists awarded the 15th Baloise Art Prize at Art Basel in 2013, won the first International Tiberius Art Award Dresden in 2014 and was the Standard Bank Young Artist for Visual Arts in 2015. Wa Lehulere was also the recipient of an Ampersand Foundation residency in New York in 2012. In 2017, he was Deutsche Bank’s ‘Artist of the Year’, the recipient of the fourth Malcolm McLaren Award and a finalist in the Future Generation Art Prize in Kyiv, Ukraine.

His work is represented in several notable public and institutional collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago (USA), Centre Pompidou (France), Deutsche Bank (Germany), Es Baluard (Spain), Hirshhorn Museum (USA) and Tate London (UK).

—

curriculum vitae

1984 Born in Cape Town, South Africa

Lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa

education

2011 BA Fine Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, ZA

selected solo exhibitions

2025 Morolong, The Sun Sleeps Between my Eyelids, Johannes Stegmann Art Gallery, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

2025 Untitled (Amarhoqololo), blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2023 25 Years Baloise Art Prize, Art Forum Baloise Park, Basel, Switzerland

2023 To Every Earth its Blood, Galerie Tschudi, Zurich, Switzerland

2023 Bring Back Lost Love, blank projects, Cape Town

2021 I Love You Too, Manchester International Festival 2021, Manchester

2021 Bring Back Lost Love, Göteborg Konsthall, Göteborg

2020 Where Did the Sky Go, Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz

2019 I cut my skin to liberate the splinter, Tate Modern, London

2018 not even the departed stay grounded, Marian Goodman Gallery, London

2018 Here I am, a concrete man, throwing himself into abstraction, Stevenson, Cape Town

2018 Bird Song, Pasquart Art Centre, Biel

2017 Bird Song, Maxxi, Rome

2017 Bird Song, Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Berlin

2016 In All My Wildest Dreams, Art Institute of Chicago, USA

2016 The knife eats at home, Stevenson, Johannesburg

2015 Sincerely Yours, Gasworks, London

2015 History will Break your Heart, National Arts Festival, Grahamstown; Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Art Museum, Port Elizabeth; Tatham Art Gallery, Pietermaritzburg; Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

2015 To whom it may concern, Stevenson, Cape Town

2014 Tiberius Art Award, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden

2014 A Conversation with a Homeless Piece of Grass, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg

2013 Sleep is for the Gifted, Lombard Freid Gallery, New York

2012 Some Deleted Scenes Too, Stevenson, Johannesburg

2011 Thirty Minutes of Amnesia: Act 1, Goethe-Institut, Johannesburg

2009 Ubontsi: Sharp Sharp!, Association for Visual Arts, Cape Town

selected group exhibitions

2025 Counting, Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz, Switzerland

2025 The Children are Now, Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh, UK

2025 From the Vault, In the Current, and On the Cusp, The Stellenbosch Triennale 2025, Oude Libertas, Rupert Museum and the Stellenbosch University Museum, Stellenbosch, South Africa

2024 Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics, LACMA, Los Angeles, USA

2024 We, the People (30 years of Democracy in South Africa), Norval Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2024 How Language Invents the World, Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur, Switzerland

2024 Hair Pieces, Melbourne Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, Australia

2024 In Conversation: The Museum and the Collection, Es Baluard Museu d’Art Contemporani de Palma, Palma, Spain

2023 Arte Povera and South African Art: In Conversation, Wits Art Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa

2023 Long-distance Friendships, 14th Kaunas Biennial, Kaunas, Lithuania

2023 You to Me, Me to You, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2023 lO, blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2022 Beyond the Surface: Collage, Mixed Media and Textile Works from the Collection, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, USA

2022 The Future is Behind Us, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2021 History’s Footnote, Marres, Huis voor Hedendaagse Cultuur, Maastricht, The Netherlands

2021 Memory of Defence: Physical and Mental Architectures, Es Baluard, Palma, Spain

2021 GROUPS AND SPOTS, Zeitgenössische Kunst Bei Der Baloise, museum franz gertsch, Burgdorf, Switzerland

2021 Stories of Resistance, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, St. Louis, USA

2020 In aller Munde - von Pieter Bruegel to Cindy Sherman, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg, Germany

2020 Ubuntu - The Harry David Art Collection, National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens, Athens, Greece

2020 Gobal(e) Resistance, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

2020 Beyond the Black Atlantic, Kunstverein Hannover, Germany

2019 Ernest Mancoba: I Shall Dance in a Different Society, Center Pompidou, Paris, France

2019 May You Live in Interesting Times, 58th Venice Biennale, Italy

2019 Leaving the Echo Chamber, 14th Sharjah Biennale, UAE

2018 9 More Weeks, Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa

2018 Both, and, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa

2018 Sculpture, Institute of Contemporary Art Indian Ocean, Mauritius

2018 O Trângulo Antlântico, 11th Mercosul Biennal, Porto Alegre, Brazil

2018 More For Less, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2018 Tell Freedom. 15 South African Artists, Kunsthal KAdE, Amersfoort, The Netherlands

2017 Future Generation Art Prize, PinchukArtCenter, Kyiv

2017 The South African Pavilion without Walls, Performa 17, New York, USA

2017 Buried in the Mix, MEWO Kunsthalle, Memmingen, Germany

2017 15th Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul Modern, Istanbul, Turkey

2017 The New Parthenon, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa

2017 Art / Afrique, le nouvel atelier, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France

2017 NERIRI KIRURU HARARA, 9th SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul, Seoul Museum of Art, South Korea

2017 Dak’Art, 12th Dakar Biennale, Senegal

2017 Still (the) Barbarians, EVA International Irish Biennial, Limerick City, Ireland

2015 Sightings, KZNSA Gallery, Durban, South Africa

2015 Drawing: The Bottom Line, S.M.A.K., Gent, Belgium

2015 Edinburgh Arts Festival, Edinburgh, Scotland

2015 African Odysseys, Le Brass, Brussels, Belgium

2015 Liberated Subjects: Present Tense, Foundation De 11 Lijnen, Oudenburg, Belgium

2014 The Grave Step, 8th Berlin Biennale, Germany

2014 This is not Africa, This is Us, West Den Haag, The Netherlands

2014 Public Intimacy: Art and Other Ordinary Acts in South Africa, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, USA

2013 On the resonance of the literary outcry in the visual arts, Martinique International Biennale, Le Forte De France, Martinique

2013 A Sculptural Premise, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa

2013 My Joburg, La Maison Rouge, Paris, France

2013 My Joburg, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany

2013 Museum as Hub, Center Historical Reenactments: After-after Tears, New Museum, New York, USA

2012 If A Tree…, Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa

2012 Home where?, Lombard Freid Projects, New York, US

2012 Air de Lyon, Fundacion Proa, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2012 The Ungovernables – New Museum Triennial, New Museum, New York, USA

2011 A Terrible Beauty is Born, 11th Lyon Biennale, Museum of Contemporary Art, Lyon, France

2011 Agter die Berge, 7 Hours, Berlin, Germany

2010 Xenoglossia: A Research Project, Center for Historical Reenactments, Johannesburg, South Africa

2010 MTN New Contemporaries Award, KZNSA Gallery, Durban, South Africa

2010 US, Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

2010 1 hour of VIDEOart!, Galerie Rupert Walser, Munich, Germany

2010 Koma + Ulwaluko: Politics and Poetics of Making Manhood, Polokwane Art Museum, Polokwane, South Africa

2009 Dada South?, Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

2009 Bring me a leaf of grass from the edge of the image: Dioptic, Weinheim, Germany

2009 Rites of Fealty/Rites of Passage, Bag Factory, Johannesburg, South Africa

2009 Identity – An Imagined State, Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos, Nigeria

2009 Nothing Ever Changes, Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees, Oudtshoorn, South Africa

2008 Performing South Africa, Hebbel am Ufer Theatre, Berlin, Germany

2008 Scratching the Surface Vol 1, Association for Visual Arts, Cape Town, South Africa

2008 World One Minutes, Today Art Museum, Beijing, China

2008 Spier Contemporary 07, Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

2008 Eskaleni: Spatial Practices, Afrika Cultural Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa

2007 Works on Paper, Blank Projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2007 Spier Contemporary 07, Spier Estate, Cape Town, South Africa

2007 A Legacy of Men, Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

2007 Akuchangywa – Cape 07 fringe, Kwa Mlamli, Gugulethu, South Africa

2005 Women Spaces, Annexe, Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

residencies + awards

2022 IASPIS residency, Swedish Arts Grant Committee, Stockholm, Sweden

2019 Laying bare: Studio process at the Museum, Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, South Africa

2017 4th Malcom McLaren Award, Performa 17, New York

2017 Deutsche Bank Artist of the Year

2015 Standard Bank Young Artist for Visual Art

2014 International Tiberius Art Award Dresden

2013 15th Baloise Art Prize, Art Basel

2013 Guest Resident at Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2012 Tollman Award for the Visual Arts

2012 Swiss Arts Council Residency, PROGR, Bern, Switzerland

2012 Ampersand Foundation Fellowship, New York, USA

2011 Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Switzerland

2010 MTN New Contemporaries Award

2010 Sommerakademie, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Switzerland

2010 Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship, Bowdoin College, Brunswick, USA

2007 Spier Contemporary Award

—

curriculum vitae

1984 Born in Cape Town, South Africa

Lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa

education

2011 BA Fine Arts, University of the Witwatersrand, ZA

selected solo exhibitions

2025 Morolong, The Sun Sleeps Between my Eyelids, Johannes Stegmann Art Gallery, University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa

2025 Untitled (Amarhoqololo), blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2023 25 Years Baloise Art Prize, Art Forum Baloise Park, Basel, Switzerland

2023 To Every Earth its Blood, Galerie Tschudi, Zurich, Switzerland

2023 Bring Back Lost Love, blank projects, Cape Town

2021 I Love You Too, Manchester International Festival 2021, Manchester

2021 Bring Back Lost Love, Göteborg Konsthall, Göteborg

2020 Where Did the Sky Go, Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz

2019 I cut my skin to liberate the splinter, Tate Modern, London

2018 not even the departed stay grounded, Marian Goodman Gallery, London

2018 Here I am, a concrete man, throwing himself into abstraction, Stevenson, Cape Town

2018 Bird Song, Pasquart Art Centre, Biel

2017 Bird Song, Maxxi, Rome

2017 Bird Song, Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Berlin

2016 In All My Wildest Dreams, Art Institute of Chicago, USA

2016 The knife eats at home, Stevenson, Johannesburg

2015 Sincerely Yours, Gasworks, London

2015 History will Break your Heart, National Arts Festival, Grahamstown; Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Art Museum, Port Elizabeth; Tatham Art Gallery, Pietermaritzburg; Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

2015 To whom it may concern, Stevenson, Cape Town

2014 Tiberius Art Award, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden

2014 A Conversation with a Homeless Piece of Grass, Hamburger Kunsthalle, Hamburg

2013 Sleep is for the Gifted, Lombard Freid Gallery, New York

2012 Some Deleted Scenes Too, Stevenson, Johannesburg

2011 Thirty Minutes of Amnesia: Act 1, Goethe-Institut, Johannesburg

2009 Ubontsi: Sharp Sharp!, Association for Visual Arts, Cape Town

selected group exhibitions

2025 Counting, Galerie Tschudi, Zuoz, Switzerland

2025 The Children are Now, Talbot Rice Gallery, Edinburgh, UK

2025 From the Vault, In the Current, and On the Cusp, The Stellenbosch Triennale 2025, Oude Libertas, Rupert Museum and the Stellenbosch University Museum, Stellenbosch, South Africa

2024 Imagining Black Diasporas: 21st-Century Art and Poetics, LACMA, Los Angeles, USA

2024 We, the People (30 years of Democracy in South Africa), Norval Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2024 How Language Invents the World, Bündner Kunstmuseum, Chur, Switzerland

2024 Hair Pieces, Melbourne Heide Museum of Modern Art, Melbourne, Australia

2024 In Conversation: The Museum and the Collection, Es Baluard Museu d’Art Contemporani de Palma, Palma, Spain

2023 Arte Povera and South African Art: In Conversation, Wits Art Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa

2023 Long-distance Friendships, 14th Kaunas Biennial, Kaunas, Lithuania

2023 You to Me, Me to You, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2023 lO, blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2022 Beyond the Surface: Collage, Mixed Media and Textile Works from the Collection, Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, Durham, USA

2022 The Future is Behind Us, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2021 History’s Footnote, Marres, Huis voor Hedendaagse Cultuur, Maastricht, The Netherlands

2021 Memory of Defence: Physical and Mental Architectures, Es Baluard, Palma, Spain

2021 GROUPS AND SPOTS, Zeitgenössische Kunst Bei Der Baloise, museum franz gertsch, Burgdorf, Switzerland

2021 Stories of Resistance, Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis, St. Louis, USA

2020 In aller Munde - von Pieter Bruegel to Cindy Sherman, Kunstmuseum Wolfsburg, Wolfsburg, Germany

2020 Ubuntu - The Harry David Art Collection, National Museum of Contemporary Art Athens, Athens, Greece

2020 Gobal(e) Resistance, Centre Pompidou, Paris, France

2020 Beyond the Black Atlantic, Kunstverein Hannover, Germany

2019 Ernest Mancoba: I Shall Dance in a Different Society, Center Pompidou, Paris, France

2019 May You Live in Interesting Times, 58th Venice Biennale, Italy

2019 Leaving the Echo Chamber, 14th Sharjah Biennale, UAE

2018 9 More Weeks, Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa

2018 Both, and, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa

2018 Sculpture, Institute of Contemporary Art Indian Ocean, Mauritius

2018 O Trângulo Antlântico, 11th Mercosul Biennal, Porto Alegre, Brazil

2018 More For Less, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2018 Tell Freedom. 15 South African Artists, Kunsthal KAdE, Amersfoort, The Netherlands

2017 Future Generation Art Prize, PinchukArtCenter, Kyiv

2017 The South African Pavilion without Walls, Performa 17, New York, USA

2017 Buried in the Mix, MEWO Kunsthalle, Memmingen, Germany

2017 15th Istanbul Biennial, Istanbul Modern, Istanbul, Turkey

2017 The New Parthenon, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa

2017 Art / Afrique, le nouvel atelier, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, France

2017 NERIRI KIRURU HARARA, 9th SeMA Biennale Mediacity Seoul, Seoul Museum of Art, South Korea

2017 Dak’Art, 12th Dakar Biennale, Senegal

2017 Still (the) Barbarians, EVA International Irish Biennial, Limerick City, Ireland

2015 Sightings, KZNSA Gallery, Durban, South Africa

2015 Drawing: The Bottom Line, S.M.A.K., Gent, Belgium

2015 Edinburgh Arts Festival, Edinburgh, Scotland

2015 African Odysseys, Le Brass, Brussels, Belgium

2015 Liberated Subjects: Present Tense, Foundation De 11 Lijnen, Oudenburg, Belgium

2014 The Grave Step, 8th Berlin Biennale, Germany

2014 This is not Africa, This is Us, West Den Haag, The Netherlands

2014 Public Intimacy: Art and Other Ordinary Acts in South Africa, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, USA

2013 On the resonance of the literary outcry in the visual arts, Martinique International Biennale, Le Forte De France, Martinique

2013 A Sculptural Premise, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa

2013 My Joburg, La Maison Rouge, Paris, France

2013 My Joburg, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Germany

2013 Museum as Hub, Center Historical Reenactments: After-after Tears, New Museum, New York, USA

2012 If A Tree…, Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa

2012 Home where?, Lombard Freid Projects, New York, US

2012 Air de Lyon, Fundacion Proa, Buenos Aires, Argentina

2012 The Ungovernables – New Museum Triennial, New Museum, New York, USA

2011 A Terrible Beauty is Born, 11th Lyon Biennale, Museum of Contemporary Art, Lyon, France

2011 Agter die Berge, 7 Hours, Berlin, Germany

2010 Xenoglossia: A Research Project, Center for Historical Reenactments, Johannesburg, South Africa

2010 MTN New Contemporaries Award, KZNSA Gallery, Durban, South Africa

2010 US, Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

2010 1 hour of VIDEOart!, Galerie Rupert Walser, Munich, Germany

2010 Koma + Ulwaluko: Politics and Poetics of Making Manhood, Polokwane Art Museum, Polokwane, South Africa

2009 Dada South?, Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

2009 Bring me a leaf of grass from the edge of the image: Dioptic, Weinheim, Germany

2009 Rites of Fealty/Rites of Passage, Bag Factory, Johannesburg, South Africa

2009 Identity – An Imagined State, Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos, Nigeria

2009 Nothing Ever Changes, Klein Karoo Nasionale Kunstefees, Oudtshoorn, South Africa

2008 Performing South Africa, Hebbel am Ufer Theatre, Berlin, Germany

2008 Scratching the Surface Vol 1, Association for Visual Arts, Cape Town, South Africa

2008 World One Minutes, Today Art Museum, Beijing, China

2008 Spier Contemporary 07, Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

2008 Eskaleni: Spatial Practices, Afrika Cultural Centre, Johannesburg, South Africa

2007 Works on Paper, Blank Projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2007 Spier Contemporary 07, Spier Estate, Cape Town, South Africa

2007 A Legacy of Men, Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

2007 Akuchangywa – Cape 07 fringe, Kwa Mlamli, Gugulethu, South Africa

2005 Women Spaces, Annexe, Iziko South African National Gallery, Cape Town, South Africa

residencies + awards

2022 IASPIS residency, Swedish Arts Grant Committee, Stockholm, Sweden

2019 Laying bare: Studio process at the Museum, Zeitz MOCAA, Cape Town, South Africa

2017 4th Malcom McLaren Award, Performa 17, New York

2017 Deutsche Bank Artist of the Year

2015 Standard Bank Young Artist for Visual Art

2014 International Tiberius Art Award Dresden

2013 15th Baloise Art Prize, Art Basel

2013 Guest Resident at Rijksakademie, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

2012 Tollman Award for the Visual Arts

2012 Swiss Arts Council Residency, PROGR, Bern, Switzerland

2012 Ampersand Foundation Fellowship, New York, USA

2011 Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Switzerland

2010 MTN New Contemporaries Award

2010 Sommerakademie, Zentrum Paul Klee, Bern, Switzerland

2010 Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship, Bowdoin College, Brunswick, USA

2007 Spier Contemporary Award

— publications

2021 Wa Lehulere, K. I Love You Too. Pureprint, UK.

2021 Wa Lehulere, K. Bring Back Lost Love. Göteborgs Konsthall, Sweden.

2018 9 More Weeks: Kemang Wa Lehulere in conversation with Sinazo Chiya. Cape Town: Stevenson.

2017 Kemang Wa Lehulere: Bird Song. Texts by Carlos Gamerro, Victoria Noorthoorn, Kate Nesin and Elvira Dyangani Ose. Berlin: Deutsche Bank.

2017 Jamal, A. ‘White Art’. In the World: Essays on Contemporary South African Art, Milan: Skira.

2015 Kemang Wa Lehulere. Standard Bank Young Artist of the Year Catalogue. Text by Kwezi Gule and Hans Ulrich Obrist. Cape Town: Stevenson.

2014 Hertz, Betti-Sue. Public Intimacy: Art and Other Ordinary Acts in South Africa, San Francisco: Verba Buena Center for the Arts.

2013 Lehrer-Graiwer, Sarah. ‘Kemang Wa Lehulere’. Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing. London: Phaidon.

2013 Obrist, Hans Ulrich. Do It: The Compendium. New York: OAP 2013 Aisemberg, Paula and Antoine de Galbert. My Joburg. Lyon: Fage.

2012 Kemang Wa Lehulere: Some Deleted Scenes Too, Cape Town: Stevenson.

2007 Van den Berg, Clive and Jay Pather. Spier Contemporary 2007. Cape Town.

— selected press

2023 Moloi, N. Kemang Wa Lehulere. Artforum [online] (published May 2023).

2023 Moloi, N. Time is an exaggeration: ‘The Future Is Behind Us’ at A4. ArtThrob [online] (published 17 April 2023).

2023 Blackman, M. Kemang Wa Lehulere Summons a Black Intellectual Tradition. ArtReview [online] (published 28 March 2023).

2023 Nkomo, V. Notes on precarity/ Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘Bring Back Lost Love’. ArtThrob [online] (published 21 February 2023).

2022 O Toole, S. South African artists taking over Chicago, Bonteheuwel style. Mail and Guardian (published 6 May 2022).

2021 Harris, S. Manchester international festival 2021: the best community art, from Cephas Williams to Kemang Wa Lehulere. The Guardian (published 29 June 2021).

2020 Leiman, L. Love songs and lamentations: How Kemang Wa Lehulere expands the canon. Arts24 [online] (published 22 June 2020).

2020 Fusi, L. (Moderator). Artists in Dialogue: Kemang Wa Lehulere & Francois-Xavier Gbre. Unframed [online] (published 1 April 2020).

2019 Leiman, L. immersive installations: the visual language of Kemang Wa lehulere. House and Leisure. (published 5 March 2019).

2018 Bourland, I. One Take: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s Performance of Self-Excavation. Frieze Magazine [online] (published 30 October 2018).

2018 Keam, S. Compulsive Storytelling: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘not even the departed stay grounded’. ArtThrob [online] (published 5 October 2018).

2018 O’Toole, Sean. History Channel: South African artist Kemang Wa Lehulere pieces together the past for a new show in London. Wallpaper (published October 2018).

2018 Joja, A. Contemporary Artist Kemang Wa Lehulere Explores Time, Freedom And History. Wanted (published 20 September 2018).

2018 Tsotsi, T. Kemang Wa Lehulere: Concrete in Abstraction. Africanah (published 4 March 2018)

2018 Minnar, M. Follow the dramatic clues, ignore the artspeak. Business Day [online] (published May 2020).

2017 Freeman, N. Performa Names Kemang Wa Lehulere Winner of Fourth Malcolm Mclaren Award. ArtNews [online] (published November 2017).

2017 Kritzinger, N. The Songs We are Taught to Sing: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘Bird Song’. ArtThrob [online] (published July 2017).

2017 Furtado, Will. Bird Song: Paying Tribute to Personal and Collective Traumas. Contemporary And [online] (published May 2017).

2017 Kemang Wa Lehulere: Bird Song. Art Matter Magazine [online] (published January 2017).

2016 Sulcas, R. South Africa’s Rising Art Star Builds His New Stage in Chicago. New York Times (published November 2016).

2016 Valentine, V. L. At the Art Institute of Chicago, Kemang Wa Lehulere Mines South Africa’s History, Imagines Its Future. Culture Type [online] (published October 2016).

2016 Jayawardane, M.N. Bad Education. Even, Fall Issue.

2016 Mahashe, G. Making History: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘The Knife Eats at Home’. ArtThrob [online] (published August 2016).

2016 Sosibo, K. ‘Wa Lehulere’s new take on education’. Mail and Guardian [online] (published June 2016).

2016 lnggs, A. Kemang Wa Lehulere, History Will Break Your Heart. Asymptote Journal, Spring.

2015 Mara De Wachter, E. Kemang Wa Lehulere Sincerely yours. Frieze [online] (published October 23 2015).

2015 O’Toole, S. Kemang Wa Lehulere. Artforum [online] (published 25 August).

2015 Farago, Jason. Portfolio: The art of Kemang Wa Lehulere, and a visit to Cape Town. Even, Summer [online].

2015 Bezuidenhout, V. ‘Rewriting History: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s History Will Break Your Heart’. ArtThrob [online] (published 13 July 2015).

2015 Smith, T. Artist ensures lost art paints a new narrative. Cape Argus [online] (published 10 July 2015).

2015 Leibbrandt, T. Investigating Kemang Wa Lehulere. ArtThrob [online] (published 7 March 2015).

2015 Dantas, N. Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘To whom it may concern’. Art Agenda [online] (published 9 February 2015).

2015 Jamal, A. Evocative activist. Financial Times, (published 5 February 2015).

2015 Smith, T. School desks, ceramic dogs and letters ... Cape Argus (published 4 February 2015).

2015 Joja, A.M. Artist Kemang Wa Lehulere’s journey through relics and erasures. Mail & Guardian (published 30 January 2015).

2015 Leiman, L. A Brief Conversation with Kemang Wa Lehulere, Winner of the 2015 Standard Bank Young Artist Award for Visual Art. Between 10 and 5 [online].

2014 Wa Lehulere bekroon. Die Burger (published 3 May 2014).

2013 SA artist wins major award at Art Basel. Mail & Guardian, (published 12 June 2013).

2013 Odufunade, B. The Artist: Kemang Wa Lehulere. Arise Live [online].

2013 Mthimkhulu, P. New artists announced for 55th La Biennale di Venezia. Department of Arts and Culture [online] (published 24 April 2013).

2012 In conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Art Basel Miami Beach Salon [online video] (published 19 December 2012).

2012 Twala, P. Kemang Wa Lehulere Producing the Gift of Art. Barcoded Magazine (published January 2012).

2011 Smith, K. Kemang Wa Lehulere. Wanted Magazine (published 21 September 2011).

2011 Sassen, R. He leaves no trace. Sunday Times (published 4 December 2011).

2010 Ngcobo, G. Unearthing skeletons in history’s shallow graves: A conversation with Kemang Wa Lehulere. PASS-AGES references & footnotes, Johannesburg: Center for Historical Reenactments.

2009 Gurney, K. Doing it His Way. Destiny Magazine, (published January 2009).

2021 Wa Lehulere, K. I Love You Too. Pureprint, UK.

2021 Wa Lehulere, K. Bring Back Lost Love. Göteborgs Konsthall, Sweden.

2018 9 More Weeks: Kemang Wa Lehulere in conversation with Sinazo Chiya. Cape Town: Stevenson.

2017 Kemang Wa Lehulere: Bird Song. Texts by Carlos Gamerro, Victoria Noorthoorn, Kate Nesin and Elvira Dyangani Ose. Berlin: Deutsche Bank.

2017 Jamal, A. ‘White Art’. In the World: Essays on Contemporary South African Art, Milan: Skira.

2015 Kemang Wa Lehulere. Standard Bank Young Artist of the Year Catalogue. Text by Kwezi Gule and Hans Ulrich Obrist. Cape Town: Stevenson.

2014 Hertz, Betti-Sue. Public Intimacy: Art and Other Ordinary Acts in South Africa, San Francisco: Verba Buena Center for the Arts.

2013 Lehrer-Graiwer, Sarah. ‘Kemang Wa Lehulere’. Vitamin D2: New Perspectives in Drawing. London: Phaidon.

2013 Obrist, Hans Ulrich. Do It: The Compendium. New York: OAP 2013 Aisemberg, Paula and Antoine de Galbert. My Joburg. Lyon: Fage.

2012 Kemang Wa Lehulere: Some Deleted Scenes Too, Cape Town: Stevenson.

2007 Van den Berg, Clive and Jay Pather. Spier Contemporary 2007. Cape Town.

— selected press

2023 Moloi, N. Kemang Wa Lehulere. Artforum [online] (published May 2023).

2023 Moloi, N. Time is an exaggeration: ‘The Future Is Behind Us’ at A4. ArtThrob [online] (published 17 April 2023).

2023 Blackman, M. Kemang Wa Lehulere Summons a Black Intellectual Tradition. ArtReview [online] (published 28 March 2023).

2023 Nkomo, V. Notes on precarity/ Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘Bring Back Lost Love’. ArtThrob [online] (published 21 February 2023).

2022 O Toole, S. South African artists taking over Chicago, Bonteheuwel style. Mail and Guardian (published 6 May 2022).

2021 Harris, S. Manchester international festival 2021: the best community art, from Cephas Williams to Kemang Wa Lehulere. The Guardian (published 29 June 2021).

2020 Leiman, L. Love songs and lamentations: How Kemang Wa Lehulere expands the canon. Arts24 [online] (published 22 June 2020).

2020 Fusi, L. (Moderator). Artists in Dialogue: Kemang Wa Lehulere & Francois-Xavier Gbre. Unframed [online] (published 1 April 2020).

2019 Leiman, L. immersive installations: the visual language of Kemang Wa lehulere. House and Leisure. (published 5 March 2019).

2018 Bourland, I. One Take: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s Performance of Self-Excavation. Frieze Magazine [online] (published 30 October 2018).

2018 Keam, S. Compulsive Storytelling: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘not even the departed stay grounded’. ArtThrob [online] (published 5 October 2018).

2018 O’Toole, Sean. History Channel: South African artist Kemang Wa Lehulere pieces together the past for a new show in London. Wallpaper (published October 2018).

2018 Joja, A. Contemporary Artist Kemang Wa Lehulere Explores Time, Freedom And History. Wanted (published 20 September 2018).

2018 Tsotsi, T. Kemang Wa Lehulere: Concrete in Abstraction. Africanah (published 4 March 2018)

2018 Minnar, M. Follow the dramatic clues, ignore the artspeak. Business Day [online] (published May 2020).

2017 Freeman, N. Performa Names Kemang Wa Lehulere Winner of Fourth Malcolm Mclaren Award. ArtNews [online] (published November 2017).

2017 Kritzinger, N. The Songs We are Taught to Sing: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘Bird Song’. ArtThrob [online] (published July 2017).

2017 Furtado, Will. Bird Song: Paying Tribute to Personal and Collective Traumas. Contemporary And [online] (published May 2017).

2017 Kemang Wa Lehulere: Bird Song. Art Matter Magazine [online] (published January 2017).

2016 Sulcas, R. South Africa’s Rising Art Star Builds His New Stage in Chicago. New York Times (published November 2016).

2016 Valentine, V. L. At the Art Institute of Chicago, Kemang Wa Lehulere Mines South Africa’s History, Imagines Its Future. Culture Type [online] (published October 2016).

2016 Jayawardane, M.N. Bad Education. Even, Fall Issue.

2016 Mahashe, G. Making History: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘The Knife Eats at Home’. ArtThrob [online] (published August 2016).

2016 Sosibo, K. ‘Wa Lehulere’s new take on education’. Mail and Guardian [online] (published June 2016).

2016 lnggs, A. Kemang Wa Lehulere, History Will Break Your Heart. Asymptote Journal, Spring.

2015 Mara De Wachter, E. Kemang Wa Lehulere Sincerely yours. Frieze [online] (published October 23 2015).

2015 O’Toole, S. Kemang Wa Lehulere. Artforum [online] (published 25 August).

2015 Farago, Jason. Portfolio: The art of Kemang Wa Lehulere, and a visit to Cape Town. Even, Summer [online].

2015 Bezuidenhout, V. ‘Rewriting History: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s History Will Break Your Heart’. ArtThrob [online] (published 13 July 2015).

2015 Smith, T. Artist ensures lost art paints a new narrative. Cape Argus [online] (published 10 July 2015).

2015 Leibbrandt, T. Investigating Kemang Wa Lehulere. ArtThrob [online] (published 7 March 2015).

2015 Dantas, N. Kemang Wa Lehulere’s ‘To whom it may concern’. Art Agenda [online] (published 9 February 2015).

2015 Jamal, A. Evocative activist. Financial Times, (published 5 February 2015).

2015 Smith, T. School desks, ceramic dogs and letters ... Cape Argus (published 4 February 2015).

2015 Joja, A.M. Artist Kemang Wa Lehulere’s journey through relics and erasures. Mail & Guardian (published 30 January 2015).

2015 Leiman, L. A Brief Conversation with Kemang Wa Lehulere, Winner of the 2015 Standard Bank Young Artist Award for Visual Art. Between 10 and 5 [online].

2014 Wa Lehulere bekroon. Die Burger (published 3 May 2014).

2013 SA artist wins major award at Art Basel. Mail & Guardian, (published 12 June 2013).

2013 Odufunade, B. The Artist: Kemang Wa Lehulere. Arise Live [online].

2013 Mthimkhulu, P. New artists announced for 55th La Biennale di Venezia. Department of Arts and Culture [online] (published 24 April 2013).

2012 In conversation with Hans Ulrich Obrist, Art Basel Miami Beach Salon [online video] (published 19 December 2012).

2012 Twala, P. Kemang Wa Lehulere Producing the Gift of Art. Barcoded Magazine (published January 2012).

2011 Smith, K. Kemang Wa Lehulere. Wanted Magazine (published 21 September 2011).

2011 Sassen, R. He leaves no trace. Sunday Times (published 4 December 2011).

2010 Ngcobo, G. Unearthing skeletons in history’s shallow graves: A conversation with Kemang Wa Lehulere. PASS-AGES references & footnotes, Johannesburg: Center for Historical Reenactments.

2009 Gurney, K. Doing it His Way. Destiny Magazine, (published January 2009).

“The language of Amarhoqololo is either (1) mobilised as a slur thrown unfairly at children (sometimes by other children) when they fail to write and draw, or (2) commonly used to refer to a general failure at symbolic representation, that is, representation as it pertains to language and the visual domain. Amarhoqololo then marks a point of failure to live up to convention or points to one’s perceived susceptibility to error. Its relation to language (and speech) signals a certain psychic investment in legibility; the burden of the rational modern subject whose faculties for thought must align with one’s conscious enunciation”.

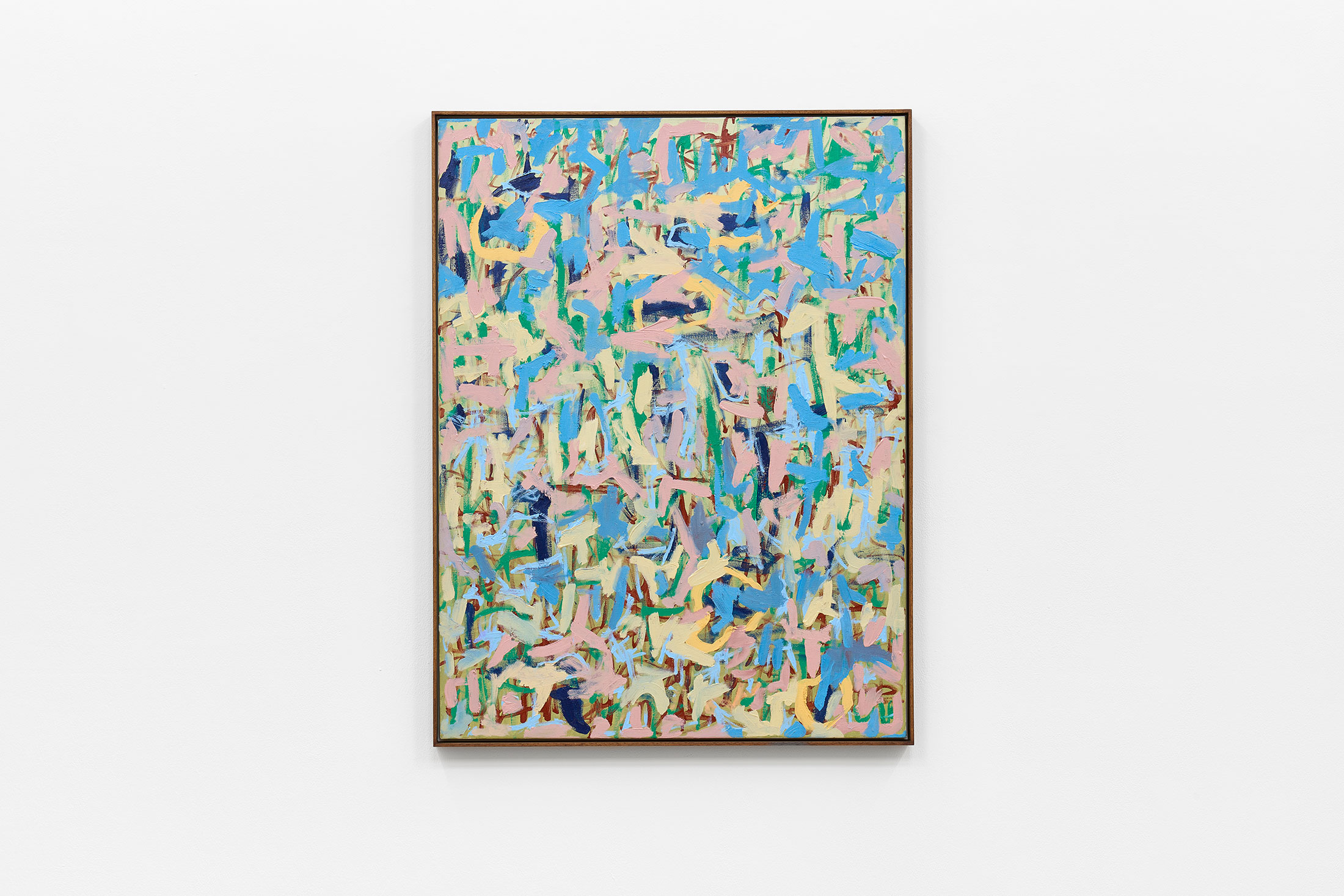

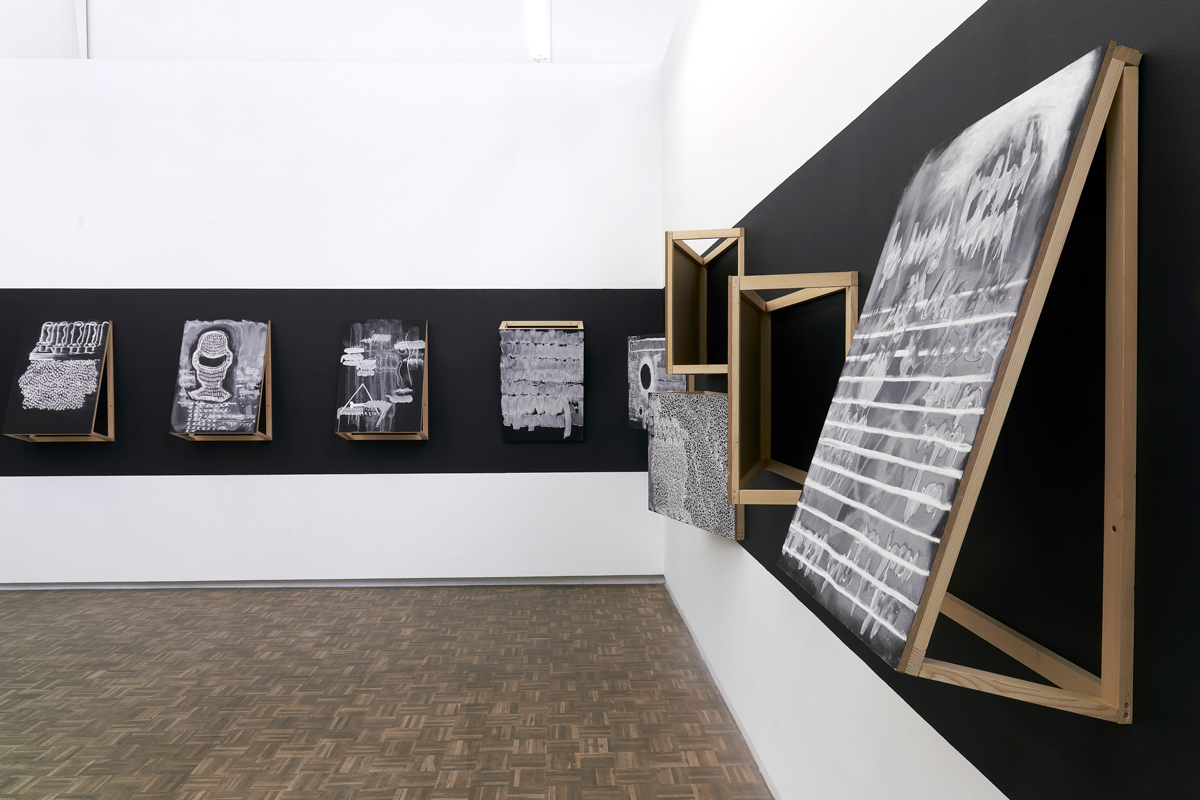

Kemang Wa Lehulere’s latest body of work consisting of abstract paintings delves into the profound weight of "Amarhoqololo," a term that marks a failure to live up to convention in symbolic representations, as ascribed to critic and artist Vusi Nkomo in the citation above – whether in the scrawl of a child's drawing or the perceived misstep of language itself, "Amarhoqololo" speaks to a deep and continuing societal preoccupation, interest and impulse to forge and make meaning, and in the face of our contemporary moment; forging meaning against a backdrop that refuses to cohere.

It is precisely within this charged terrain of competing historical narratives; overlooked narratives; and the collapse of consensus that the persistent desire for legibility in the work of Wa Lehulere finds its vital pulse. “Maybe it is a rehearsal for sense-making that I am involved with”, as Wa Lehulere says in one of his letter exchanges discussing these works with Pehr Mårtens, dated March 2025. “Each painting a baton from one painting to the other, perhaps allowing for the works the be easily read as a suite”. A notated jazz composition, an idiom that has not been uncommon in Wa Lehulere’s ouvre.

In an unsurprising act of borrowing from his vast visual language, some of the paintings in this suite are sub-lain in black paint, reminiscent of his use of black school boards. What follows are layers of abstract marks and strokes and (notes) in bewildering colour and rhythm. Acts of improvisation and spontaneous combustions of free-form composition so essential in the jazz art form, a form which Wa Lehulere is so deeply imbued with and deftly draws from.

Through these paintings, much like his use of drawing, performance, installation, and salvaged objects, Wa Lehulere champions the “susceptibility to error" not as a flaw, but as a rich ground for exploration. He gives voice to the unspoken and visible form to the intangible, often inviting collaborators to fill in the gaps that emerge from the passage of time or to grant his own memory a higher fidelity.

Wa Lehulere’s art continues to be a powerful meditation on how we make sense of the present (meaning the past) when its records are incomplete, and how, in the face of imposed legibility, new forms of symbolic representation can emerge, even if they bear the beautiful, complex marks of what was once deemed "Amarhoqololo."

- Vusi Nkomo, The legitimacy of illegibility: Kemang Wa Lehulere’s indeterminate marks (2025)

Kemang Wa Lehulere’s latest body of work consisting of abstract paintings delves into the profound weight of "Amarhoqololo," a term that marks a failure to live up to convention in symbolic representations, as ascribed to critic and artist Vusi Nkomo in the citation above – whether in the scrawl of a child's drawing or the perceived misstep of language itself, "Amarhoqololo" speaks to a deep and continuing societal preoccupation, interest and impulse to forge and make meaning, and in the face of our contemporary moment; forging meaning against a backdrop that refuses to cohere.

It is precisely within this charged terrain of competing historical narratives; overlooked narratives; and the collapse of consensus that the persistent desire for legibility in the work of Wa Lehulere finds its vital pulse. “Maybe it is a rehearsal for sense-making that I am involved with”, as Wa Lehulere says in one of his letter exchanges discussing these works with Pehr Mårtens, dated March 2025. “Each painting a baton from one painting to the other, perhaps allowing for the works the be easily read as a suite”. A notated jazz composition, an idiom that has not been uncommon in Wa Lehulere’s ouvre.

In an unsurprising act of borrowing from his vast visual language, some of the paintings in this suite are sub-lain in black paint, reminiscent of his use of black school boards. What follows are layers of abstract marks and strokes and (notes) in bewildering colour and rhythm. Acts of improvisation and spontaneous combustions of free-form composition so essential in the jazz art form, a form which Wa Lehulere is so deeply imbued with and deftly draws from.

Through these paintings, much like his use of drawing, performance, installation, and salvaged objects, Wa Lehulere champions the “susceptibility to error" not as a flaw, but as a rich ground for exploration. He gives voice to the unspoken and visible form to the intangible, often inviting collaborators to fill in the gaps that emerge from the passage of time or to grant his own memory a higher fidelity.

Wa Lehulere’s art continues to be a powerful meditation on how we make sense of the present (meaning the past) when its records are incomplete, and how, in the face of imposed legibility, new forms of symbolic representation can emerge, even if they bear the beautiful, complex marks of what was once deemed "Amarhoqololo."

Kemang Wa Lehulere was born in 1984 in Cape Town. To date, he has had solo exhibitions at Göteborg Konsthall, Sweden, Tate Modern, UK, the Pasquart Art Centre, Switzerland, MAXXI, Italy, the Deutsche Bank KunstHalle, Germany and the Art Institute of Chicago, USA. Selected group exhibitions include Centre Pompidou, Paris, 58th Venice Biennale, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, Performa 17, New York, Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, among others.

Wa Lehulere was a co-founder of Gugulective (2006), an artist-led collective based in Cape Town, and a founding member of the Center for Historical Reenactments (2010) in Johannesburg. In 2017, he was Deutsche Bank’s ‘Artist of the Year’, recieved the fourth Malcolm McLaren Award and was a finalist in the Future Generation Art Prize in Kyiv, Ukraine. He is the winner of the 2015 Standard Bank South Africa, Young Artist Award and is one of two young artists awarded the 15th Baloise Art Prize at Art Basel in 2013.

Wa Lehulere was a co-founder of Gugulective (2006), an artist-led collective based in Cape Town, and a founding member of the Center for Historical Reenactments (2010) in Johannesburg. In 2017, he was Deutsche Bank’s ‘Artist of the Year’, recieved the fourth Malcolm McLaren Award and was a finalist in the Future Generation Art Prize in Kyiv, Ukraine. He is the winner of the 2015 Standard Bank South Africa, Young Artist Award and is one of two young artists awarded the 15th Baloise Art Prize at Art Basel in 2013.

His work is represented in several notable public and institutional collections, including the Art Institute of Chicago (USA), Centre Pompidou (France), Deutsche Bank (Germany), Es Baluard (Spain), Hirshhorn Museum (USA) and Tate London (UK).

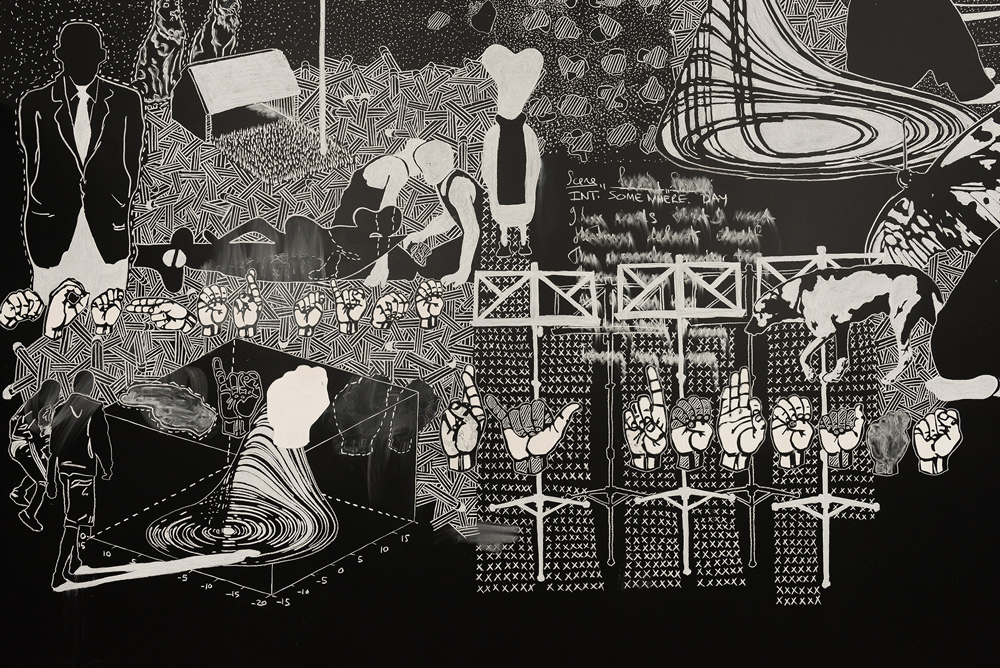

blank is pleased to present Bring Back Lost Love, a solo exhibition by Kemang Wa Lehulere. Encompassing sculptures, drawings, and installation, Bring Back Lost Love is conceived as a symphony that excavates personal and collective memory, real and imagined, to address neglected or discarded narratives of South African history. Through a retelling of stories that traverse fact and fiction, the exhibition invokes questions of land ownership and migration in relation to the various legislations that violently disinherited black South Africans of land. Bring Back Lost Love evidences Wa Lehulere’s process of unearthing as a strategy for historiographic disruption and critique. To ‘bring back’ is not only to return, but to exhume, retrieve, and reinstate.

Suspended within the central exhibition space is the installation titled Black Forest. Describing the works, Wa Lehulere states,

Collaborating again with his aunt, the artist adopted a call-and-response strategy synonymous with free jazz – in which the lead musician “calls” for a response from the ensemble to create a new and unscripted melody and rhythm – to create ERF, a body of ink drawings that depict imaginary landscapes. The drawings recall the legacy of the late artist Gladys Mgudlandlu whose bucolic, colourful landscape paintings are interpreted as a critique of the status quo by their very exclusion of political themes. Mgudlandlu was a school teacher who taught Sophia Lehulere before their families were relocated from Athlone to Gugulethu under the Group Areas Act. The drawings that form ERF are inspired by the scenery and natural elements found in Mgudlandlu’s work; specifically the murals that adorned her home, which Wa Lehulere’s aunt recalls from memory.

In Reddening of the Greens, the theme of movement and migration is carried through the installation of worn suitcases, wooden crutches and birdhouse assemblages made out of salvaged school desks. Explaining the significance of these materials and their multiple readings, Wa Lehulere recalls the journeys of German philosopher Walter Benjamin and South African writer Nat Nakasa, both of whom tragically committed suicide when in exile. Assembled together, the objects convey multiple meanings – the suitcases are representative of journeys but also displacement, while the crutch is interpreted as a means of support but also hindered progress. The incomplete birdhouses made of cut up school desks suggest the symbolic promises of freedom, and the failures of the institutions that govern, police, and educate us.

The installation Conference of the Birds is an assembly of sixteen bird-boxes constructed from salvaged school desks, interspersed with music stands, ceramic dogs, and paper scrolls, and surrounded by chalk boards protruding at angles from the walls. Taking its title from an album by the Dave Holland Quartet, Conference of the Birds is inspired by the 1993 Gatherings Act of South Africa, which allowed a maximum of fifteen protesters to gather without a permit: the sixteenth person makes the protest illegal. In addition to universal references to collectivity, freedom and peace, birds in Southern African folk tales can also allude to symbols of the female sex and gender conflicts, as well as mediators between the spiritual world and the material world. Universal symbols of instruction, the chalkboards are populated with drawings and sketches alluding to crowds of people, depicted as swarming masses of dots, or Xs in sequence. Here and there are portions of text, obliterated and obscured like the rolled up messages strewn about the floor. Through the use of these metaphors, the work speaks to ideas of connectedness, networks and communing. In South Africa, protests – often accompanied by song – are heavily policed. Though they are mass-produced as kitsch household ornaments, the presence of the ceramic Alsatian dogs in the installation is a reminder of ‘police dogs’ and the force of state violence that protesters were often met with during such gatherings.

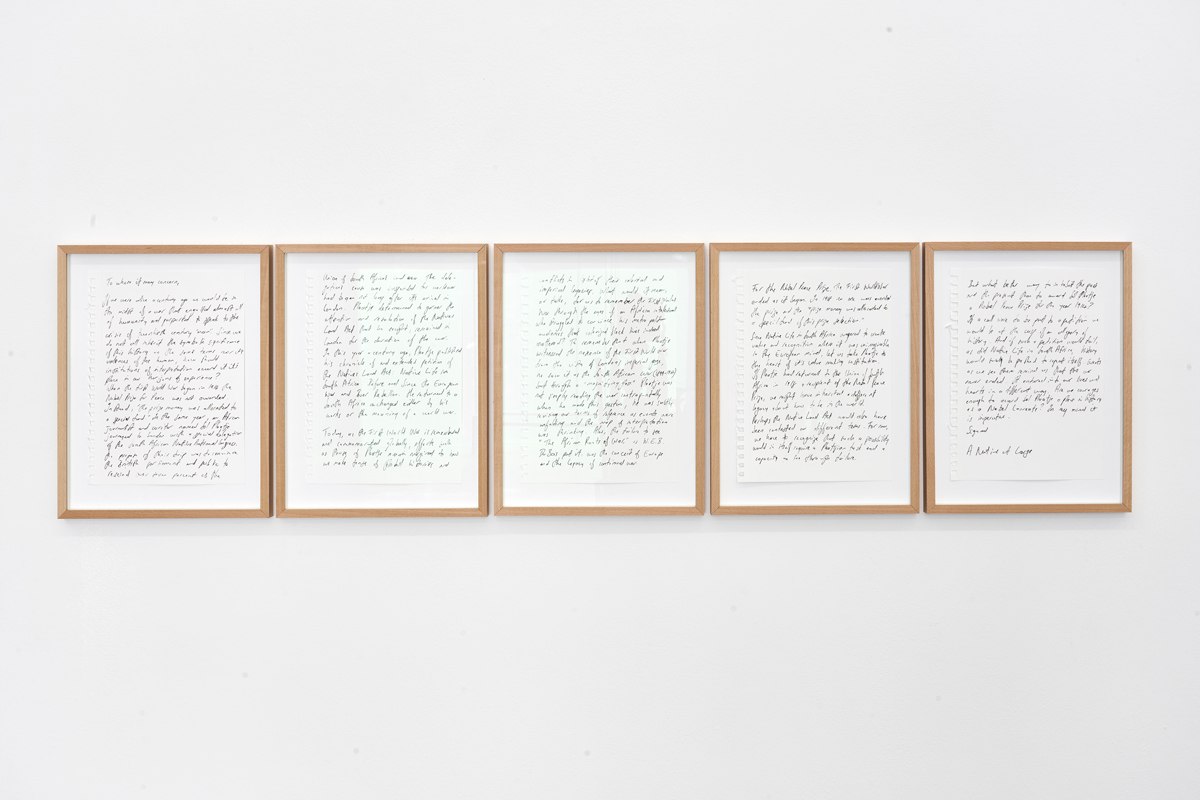

Also included in the exhibition is a letter addressed to the Nobel Peace Prize committee. In it, Wa Lehulere appeals to the institution to retrospectively honour the late author Sol T. Plaatje with the unallocated 1914 award for his monumental work, Native Life in South Africa, which was written in response to the Native Land Act. Although the institution does not award the prize posthumously, Wa Lehulere nevertheless posits the importance of acknowledging Plaatje’s contributions to literature through his chronicling of the Black experience. In doing so, the artist attempts to intervene, or collaborate with time and history by proposing a redress of recognition for Plaatje’s oeuvre.

Curator and critic Khwezi Gule writes:

“Wa Lehulere’s work is not so much about history or histories but the points at which certain (historical) trajectories are interrupted on a personal level (exile, suicide) and a systemic socio-political level (forced removals, the Land Act), and the intersection of the two. In a sense, his practice explores how the historical does not just manifest in the personal but how the personal is constitutive of the historical. Another major theme running through the artist’s practice is the abortive attempt to suture, reassemble, to graft prostheses onto these interrupted narratives and trajectories. These become surrogates for what was lost in the ruptures. Aborted, though, because the act of grafting (new) histories on old injuries serves not to ameliorate or cover up the injury but to accentuate and deepen the sense of loss.”

Bring Back Lost Love is Wa Lehulere’s first exhibition with the gallery.

Exhibition press:

Blackman, M. Kemang Wa Lehulere Summons a Black Intellectual Tradition. ArtReview [online] (published 28 March 2023)

Moloi, N. Kemang Wa Lehulere at blank projects. Artforum, vol. 61, no. 9 (published May 2023)

Suspended within the central exhibition space is the installation titled Black Forest. Describing the works, Wa Lehulere states,

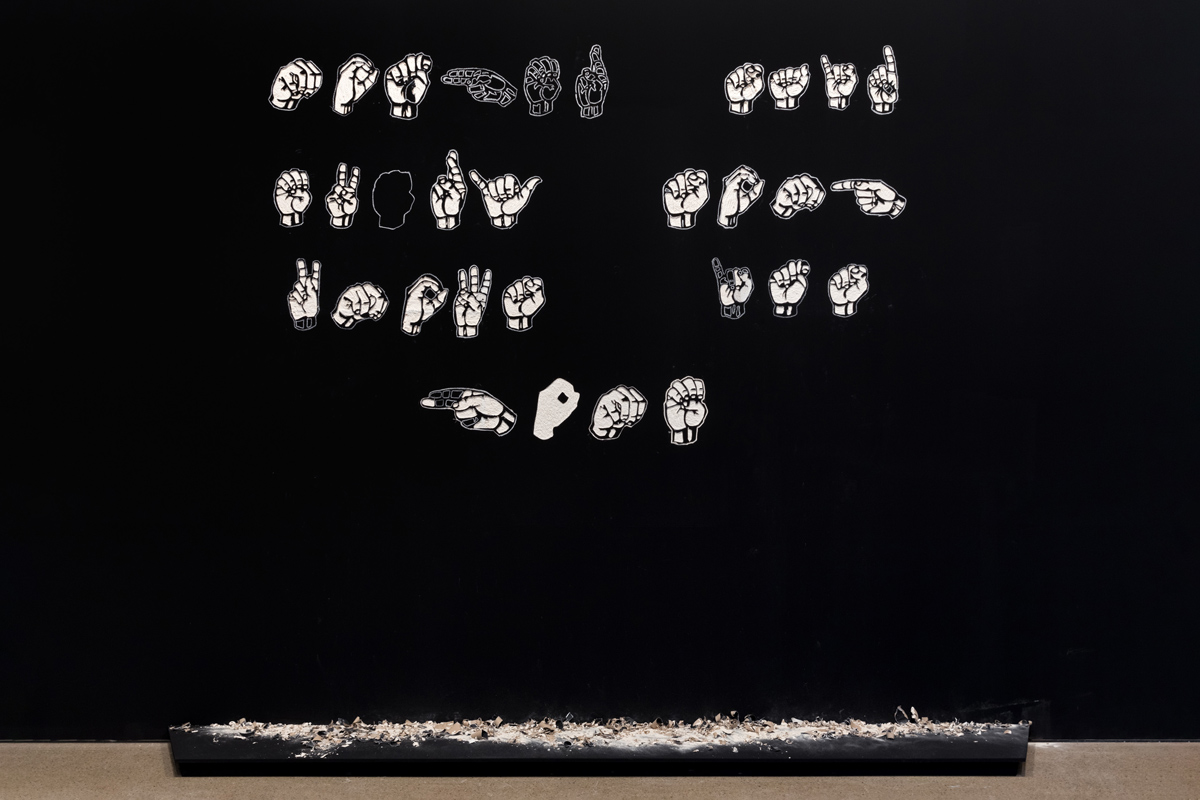

I am interested in the idea of mapping, relating to questions of displacement and land. And an inspiration for the layout of this piece comes from the Lars von Trier film, Dogville. The installation consists of blackboards as a suspended landscape with drawings and elements made from concrete, salvaged school desks and porcelain dogs. The chalk drawing is a geographical representation of the neighbourhood where I grew up in Gugulethu, Cape Town. This was also a location during apartheid, to which many black people were sent, after they had been forcibly removed from other areas that had been deemed white only. In the installation I have also integrated casts of my aunt Sophia’s hands depicting notation from the sign language alphabet, but abstracted, as I am interested in notions of (il)legibility. Upon the floor are bottles, reminiscent of Molotov cocktails, a popular weapon of protest during apartheid. Each bottle contains sand and small wrapped paper messages that function as a metaphor for the many untold stories in our community and speak to African spirituality and the communication with our ancestors. The bottles thus become markers of violence and protest and a desire for our stories to be told and heard.

Collaborating again with his aunt, the artist adopted a call-and-response strategy synonymous with free jazz – in which the lead musician “calls” for a response from the ensemble to create a new and unscripted melody and rhythm – to create ERF, a body of ink drawings that depict imaginary landscapes. The drawings recall the legacy of the late artist Gladys Mgudlandlu whose bucolic, colourful landscape paintings are interpreted as a critique of the status quo by their very exclusion of political themes. Mgudlandlu was a school teacher who taught Sophia Lehulere before their families were relocated from Athlone to Gugulethu under the Group Areas Act. The drawings that form ERF are inspired by the scenery and natural elements found in Mgudlandlu’s work; specifically the murals that adorned her home, which Wa Lehulere’s aunt recalls from memory.

In Reddening of the Greens, the theme of movement and migration is carried through the installation of worn suitcases, wooden crutches and birdhouse assemblages made out of salvaged school desks. Explaining the significance of these materials and their multiple readings, Wa Lehulere recalls the journeys of German philosopher Walter Benjamin and South African writer Nat Nakasa, both of whom tragically committed suicide when in exile. Assembled together, the objects convey multiple meanings – the suitcases are representative of journeys but also displacement, while the crutch is interpreted as a means of support but also hindered progress. The incomplete birdhouses made of cut up school desks suggest the symbolic promises of freedom, and the failures of the institutions that govern, police, and educate us.

The installation Conference of the Birds is an assembly of sixteen bird-boxes constructed from salvaged school desks, interspersed with music stands, ceramic dogs, and paper scrolls, and surrounded by chalk boards protruding at angles from the walls. Taking its title from an album by the Dave Holland Quartet, Conference of the Birds is inspired by the 1993 Gatherings Act of South Africa, which allowed a maximum of fifteen protesters to gather without a permit: the sixteenth person makes the protest illegal. In addition to universal references to collectivity, freedom and peace, birds in Southern African folk tales can also allude to symbols of the female sex and gender conflicts, as well as mediators between the spiritual world and the material world. Universal symbols of instruction, the chalkboards are populated with drawings and sketches alluding to crowds of people, depicted as swarming masses of dots, or Xs in sequence. Here and there are portions of text, obliterated and obscured like the rolled up messages strewn about the floor. Through the use of these metaphors, the work speaks to ideas of connectedness, networks and communing. In South Africa, protests – often accompanied by song – are heavily policed. Though they are mass-produced as kitsch household ornaments, the presence of the ceramic Alsatian dogs in the installation is a reminder of ‘police dogs’ and the force of state violence that protesters were often met with during such gatherings.

Also included in the exhibition is a letter addressed to the Nobel Peace Prize committee. In it, Wa Lehulere appeals to the institution to retrospectively honour the late author Sol T. Plaatje with the unallocated 1914 award for his monumental work, Native Life in South Africa, which was written in response to the Native Land Act. Although the institution does not award the prize posthumously, Wa Lehulere nevertheless posits the importance of acknowledging Plaatje’s contributions to literature through his chronicling of the Black experience. In doing so, the artist attempts to intervene, or collaborate with time and history by proposing a redress of recognition for Plaatje’s oeuvre.

Curator and critic Khwezi Gule writes:

“Wa Lehulere’s work is not so much about history or histories but the points at which certain (historical) trajectories are interrupted on a personal level (exile, suicide) and a systemic socio-political level (forced removals, the Land Act), and the intersection of the two. In a sense, his practice explores how the historical does not just manifest in the personal but how the personal is constitutive of the historical. Another major theme running through the artist’s practice is the abortive attempt to suture, reassemble, to graft prostheses onto these interrupted narratives and trajectories. These become surrogates for what was lost in the ruptures. Aborted, though, because the act of grafting (new) histories on old injuries serves not to ameliorate or cover up the injury but to accentuate and deepen the sense of loss.”

Bring Back Lost Love is Wa Lehulere’s first exhibition with the gallery.

Exhibition press:

Blackman, M. Kemang Wa Lehulere Summons a Black Intellectual Tradition. ArtReview [online] (published 28 March 2023)

Moloi, N. Kemang Wa Lehulere at blank projects. Artforum, vol. 61, no. 9 (published May 2023)