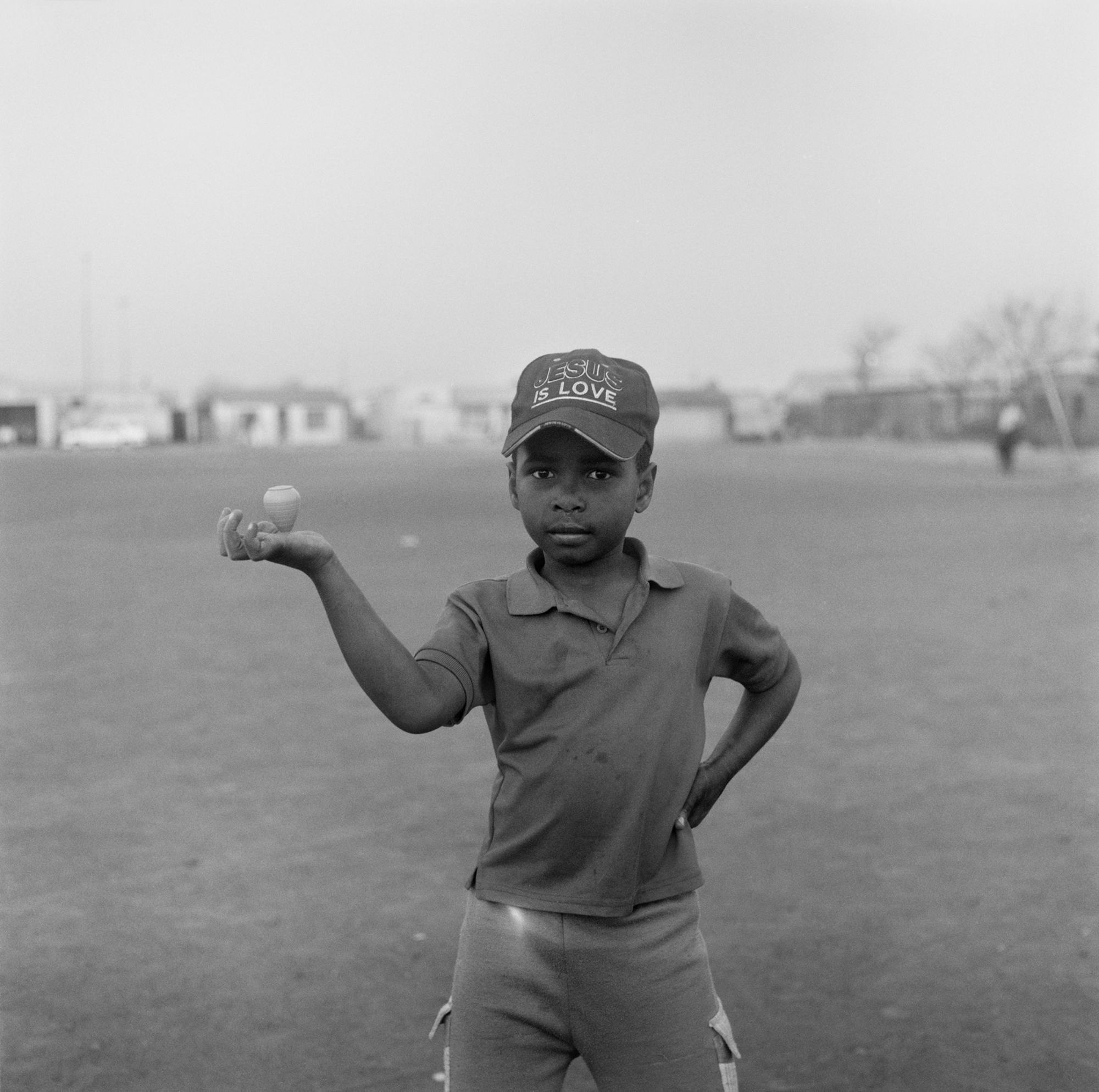

Photo: Ferrante Ferranti

Working largely in black and white format, Sabelo Mlangeni has built his practice around intimate photographs that draw out the inherent beauty in the ordinary. Mlangeni is driven by his interest in the notions of community and communing where a central part of his process requires him to spend significant time —weeks, months, sometimes years—with those he chooses to photograph; sharing intimately in their thoughts, feelings, stories and everyday lives. His practice is a continuous survey of the most challenging, beautiful and confounding aspects of the human experience.

He states:

“I have been moving around Johannesburg and its closest suburbs as someone interested in story-telling about everyday life. In my early walks, I found myself in many spaces where the situation and the living conditions were impossible to look at and to photograph. Then I started wondering, what to frame? Soon another side of the hardships emerged, and I attempted to capture that hidden beauty, that ordinary peace.”

Mlangeni has had numerous solo exhibitions to date, including most recently I have stopped time. A family portrait (2026) and Honeymoon. The happily ever after? (2025). His work has been widely exhibited both locally and internationally, including at Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington, D.C. (2026), MoMA in New York (2025), MASP in São Paulo (2025), the Norval Foundation in Cape Town (2025), The Art Institute of Chicago (2024), Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden (2024), Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation in Eschborn (2024), Museum Folkwang in Essen (2024), The 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia (2024), the Institute of Ideas & Imagination in Paris (2023), A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town (2023), Haus der Kunst / The Walther Collection in Munich (2023), Para Site in Hong Kong (2022), Huis Marseille in Amsterdam (2022), K21 in Düsseldorf (2022), Palais de Tokyo in Paris (2021), Frestas Triennial of São Paulo (2021), Lagos Biennale (2019), Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (2019), Huis Marseille Museum of Photography (2019), Wits Art Museum (2018), Savvy Contemporary (2018), Kunsthal KAde (2018), Museum Africa (2015), Liverpool Biennale (2013), Lubumbashi Biennale (2012), Lagos Photo Festival (2011), V&A Museum (2011), Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum (2010), and Johannesburg Art Gallery (2010).

Mlangeni has been awarded several prizes including the Columbia University II&I fellowship and artist residency (Paris, 2022), Africa MediaWorks Photography Prize (London, 2018), POPCAP’16 Prize for Contemporary African Photography (2016), and the Tollman Award for Visual Arts (2009). He has also had residencies at Amant (New York, 2025), A4 Arts Foundation (Cape Town, 2018), Centre de Art Waza (Lubumbashi, 2017), Walther Collection (Neu-Ulm, 2017), Akademie der Künste (Vienna, 2014), Akademie der Künste (Berlin, 2013) and Centre for Contemporary Art (Lagos, 2010). His work is represented in several institutional collections, including Museum of Art of São Paulo, the Tate Modern, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Johannesburg Art Gallery, Walther Collection, Art Institute of Chicago, KADIST, and CNAP - French national collections.

—

curriculum vitae

1980 Born in Driefontein, Mpumalanga, South Africa

education

2001 – 2004 Market Photo Workshop

solo exhibitions

2026 I have stopped time. A family portrait, ADA Project, Rome, Italy

2025 Honeymoon. The happily ever after? blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2023 Imvuselelo: The revival, Cantor Arts Center, Stanford, USA

2023 Ngiyabona Phambli, Institute of Ideas & Imagination, Paris, France

2022 Isivumelwano as part of The beauty of the world so heavy, Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, Netherlands

2021 Isivumelwano, blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2020 The Royal House of Allure, blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2018 Umlindelo wamaKholwa, Wits Art Museum, Johannesburg, South Africa

2018 Invisible Women, Memorial Dr. Antonio Agostinho Neto, Luanda, Angola

2017 Kholwa: The Longing of Belonging, Museum of Archeology, Cambridge, UK

2016 Heartbreaker, artSPACE, Auckland, New Zealand

2015 No Problem, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa

2012 Black Men in Dress and Iimbali, Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa

2012 Country Girls, Aceberg Projects, Chicago, USA

2011 Ghost Towns, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa

2010 Men Only/At Home, Brodie/Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa

2010 This is Our Time, Brodie/Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa

2007 Invisible Women, Warren Siebrits Contemporary Modern Art, Johannesburg, South Africa

2006 Invisible Women, Market Photo Workshop, Johannesburg, South Africa

selected group exhibitions

2026 Here: Pride and Belonging in African Art, Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, Washington, DC, USA

2025 New Photography 2025, MoMA, New York, USA

2025 Picture Gallery in Transformation: Recent Gifts, MASP, São Paulo, Brazil

2025 And I, a newly evolved fish, Iyatsiba Lab, Cape Town, South Africa

2025 We, The People: 30 Years of Democracy in South Africa, Norval Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2024 Project A Black Planet: The Art and Culture of Panafrica, The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA

2024 Sea and Fog, Staatliche Kunsthalle Baden-Baden, Baden-Baden, Germany

2024 Look at Us. 25 Years of Art Collection Deutsche Börse, Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation, Eschborn, Germany

2024 GROW IT, SHOW IT!, Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany

2024 We, The Purple, The Javett Art Centre, Pretoria, South Africa

2024 Foreigners Everywhere, The 60th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy

2023 A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography, Tate Modern, London, UK

2023 Common, A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2023 lO, blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2023 Trace - Formations of Likeness, Haus der Kunst / The Walther Collection, Munich, Germany

2023 Urban Cadence: Street Scenes from Lagos and Johannesburg, Middleburg College Museum of Art, Middleburg, USA

2022 A Different Now is Close Enough to Exhale on You, Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

2022 While we are embattled, Para Site, Hong Kong

2022 Shifting Dialogues: Photography from The Walther Collection, K21, Düsseldorf, Germany

2021 Ubuntu, a Lucid Dream, Palais de Tokyo, Paris, France

2021 The River is a Serpent, Frestas – Triennial of Arts 3rd edition, SESC São Paulo, São Paolo, Brazil

2021 Handle with Care, Javett Art Centre, Pretoria, South Africa

2021 Photographs In Our Mother Tongue, Standard Bank Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

2019 Ngoma: Art and Cosmology, Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

2019 the head the hand, blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2019 How to Build a Lagoon with Just a Bottle of Wine?, Lagos Biennial II, Àkéte Art Foundation, Lagos, Nigeria

2019 The Way She Looks: A History of Female Gazes in African Portraiture, Ryerson Image Centre, Toronto, USA

2019 Crossing Night: Regional Identities x Global Context, Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit, Detroit, USA

2019 Mating Birds Vol.2, KZNSA Gallery, Durban, South Africa

2018 Recent Histories – New African Photography and Video Art from the Walther Collection, Huis Marseille, Amsterdam

2018 open agenda, blank projects, Cape Town, South Africa

2018 Hacer Noche (Crossing Night), Centro Cultural Santo Domingo, Oaxaca de Juarez, Mexico

2018 Both, And, Stevenson, Cape Town, South Africa

2018 Africa State of Mind, curated by Ekow Eshun, New Art Exchange, Nottingham, UK

2018 About Whose Land Have I Lit On Now?, Savvy Contemporary, Berlin, Germany

2018 Invisible Women, Memorial Dr. Antonio Agostinho Neto, Luanda, Angola

2018 Tell Freedom. 15 African artists, Kunsthal KAde, Amersfoort, Netherlands

2017 Recent Histories – New African Photography and Video Art, Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm, Germany

2017 Urban Cadence: Street Scenes from Lagos and Johannesburg, Gund Gallery, Ohio, USA

2016 Close to Home: New Photography from Africa, The Walther Collection Project Space, New York, USA

2016 SEX, Stevenson, Johannesburg, South Africa

2015 Rise and Fall of Apartheid : Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, Museum Africa, Johannesburg, South Africa

2015 Making Africa: A Continent of Contemporary Design, Vitra Design Museum, Weil am Rhein, Germany; Guggenheim Bilbao, Spain

2014 Public Intimacy: Art and Social Life in South Africa at the Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, San Francisco, USA

2014 Apartheid and After, Huis Marseille, Amsterdam, Netherlands

2013 Rise and Fall of Apartheid: Photography and the Bureaucracy of Everyday Life, Haus der Kunst, Munich, Germany

2013 Distance and desire: Encounters with African Archive, Walther Collection, Neu Ulm, Germany

2013 Present Tense, Calouse Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon, Portugal

2013 Present Tense, Calouse Gulbenkian French Delegation, Paris, France

2013 The Unexpected Guest, Liverpool Biennale exhibition, Liverpool, UK

2012 Recontres Picha Biennale de Lumbumbashi (Lubumbashi Biennale), DRC

2012 Centre photograpie de la de Franse, Paris, France

2011 9th Rencontres de Bamako African Photography Biennale, Mali

2011 Lagos Photo Festival, Nigeria

2011 Appropriated Landscapes, Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm, Germany

2011 Figures and Fictions: Contemporary South African Photography, V&A Museum, London, UK

2011 Possible Cities: Africa in photography and video, Cantor Fitzgerald Gallery, Haverford College, Pennsylvania, USA

2010 Centre for Contemorary Art, Lagos, Nigeria

2010 Afropolis: City, Media, Art, Rautenstrauch-Joest-Museum, Cologne, Germany

2010 I am not afraid, The Market Photo Workshop, Johannesburg Art Gallery, South Africa

2008 Look Away, South African Photography Today, Kuckei+Kuckei, Berlin, Germany

residencies

2022 Institute for Ideas & Imagination, Paris, France

2018 A4 Arts Foundation, Cape Town, South Africa

2018 Ses Ditze Naus, Ibiza, Spain

2017 Centre de Art Waza, Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of Congo

2017 Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm, Germany

2016 Diep, Haven, Arques la bataille, Normandy, France

2015 Afrovibes, Amsterdam, Netherlands

2014 Akademie of art Vienna, Vienna, Austria

2013 Berlin Fellowship, Akademie der Kunste, Berlin, Germany

2012 The Center Photographique d'Ile-de-France, Paris, France

2010 Centre for Contemorary Art, Lagos, Nigeria

public and institutional collections

Tate Modern, London, UK

Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation, Germany

San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, USA

Johannesburg Art Gallery, Johannesburg, South Africa

Walther Collection, Neu-Ulm, Germany

Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, USA

KADIST, Paris, France

Sasol, Johannesburg, South Africa

SABC Art Collection, Johannesburg, South Africa

— publications

2024 Dunster, F. & Gordon, T. Photography - A Queer History. Ilex, UK.

2023 Bonsu, O. A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography. Tate publishing (published July 2023).

2022 Bonsu, O. African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century. Chronicle Books LLC / Tate, UK.

2022 Balogun, E. et al. Isivumelwano. Fw:Books, Amsterdam (published May 2022).

2022 Allen, S. Tate Photography Series: Sabelo Mlangeni. Tate Publishing (published May 2022).

2021 Underwood, J. L. & Okeke-Agulu, C et al. African Artists: From 1882 to Now. Phaidon Press, UK. Published 17 November 2021.

2019 Cane, J. Civilising Grass: The art of the lawn on the South African Highveld. NYU Press, US.

2018 Sabelo Mlangeni: Umlindelo wamaKholwa. Wits Art Museum, South Africa.

2011 Sabelo Mlangeni: At Home / Ghost Towns. Michael Stevenson, South Africa.

2010 Sabelo Mlangeni: Country Girls. Michael Stevenson, South Africa.

2009 Sabelo Mlangeni: Men Only. Michael Stevenson, South Africa.

— selected press

2025 O’Toole, S. Sabelo Mlangeni. Artforum [online] (published September 2025).

2025 Chepape, L. Looking back in black and white to see more clearly [online] (published April 2025).

2024 Sincuba, T. Kamogelo Walaza on Curating Sabelo Mlangeni’s Solo “Ngiyabona Phambili” [online] (published September 2025).

2024 Littlewood, C. Collective (un)doings. Photomonitor: [online] (published January 2024).

2024 Mendenhall-Dever, S. Q&A/ Visiting Artist Sabelo Mlangeni on photographing South African communities and identities. The Standford Daily [online] (published 09 January 2024).

2023 Tobin, K. Joy, tenderness and intimacy are celebrated by artists in London. Wallpaper [online] (published 23 December 2023).

2023 Bruno, G. How ‘Pictures of Us’ Channels the Universality of the Human Experience. ELEPHANT [online] (published 14 December 2023).

2023 Shinners, K. Common. e-flux [online] (published 22 June 2023).

2023 The meaning of work in the modern world: a photography special. Financial Times [online] (published 5 January 2023).

2022 Stretch to the limit! Images from the Tate collection – in pictures. The Guardian. [online] (published 18 May 2022)

2022 Nigeria: a royal house, persecuted LGBT refuge. Altus Intel. [online] (published 2 January 2022).

2021 Mavuso, T. & Mlangeni, S. Forgotten Spools: Looking Through the Archives of Cynthia Mavuso. Mail & Guardian. [online] (published 1 October 2021).

2021 Stevens, N. ‘Photographs In Our Mother Tongue’: The new South Africa under scrutiny’. Mail and Guardian [online] (published 10 May 2021).

2021 Nkomo, V. History is happening: ‘The thing itself exists everywhere’ at blank projects. ArtThrob [online] (published 23 March 2021).

2020 Dinsdale. E. Sabelo Mlangeni’s moving photos of life inside a Nigerian queer safe house. Dazed [online] (published 29 September 2020).

2020 Moloi, N. Against erasure and forgetting: Sabelo Mlangeni and Igshaan Adams at blank projects. ArtThrob [online] (published 11 February 2020).

2020 Collison, C. Sabelo Mlangeni’s intimate portrayal of queer Nigeria. New Frame [online] (7 February 2020).

2018 Sabelo Mlangeni Exhibition on Zion Churches shows in Johannesburg. Afropolitian Explosive, South Africa [online] (published 8 December 2018).

2018 Confessional Documentary: Sabelo Mlangeni and Wolfgang Tillmans in Johannesburg. ArtThrob, South Africa [online] (published 26 October 2018).

2018 Seymour, T. Sabelo Mlangeni. Nataal, UK [online] (published 11 October 2018).

2018 Warner, M. Sabelo Mlangeni’s images of South Africa. British Journal of Photography, UK [online] (published 5 October 2018).

2018 Mcutha, N. Umlindelo wamaKholwa: Sabelo Mlangeni’s zionism photography. Between 10 and 5, South Africa [online] (published 26 July 2018).

2018 Stevens, N. The Believers: Sabelo Mlangeniʼs ‘Umlindelo wamaKholwaʼ. ArtThrob, South Africa [online] (published 17 July 2018).

2018 Lim, D. Quiet images of the Zionist Christian Church. City Press, South Africa [online] (published 8 July 2018).

2018 Anstey, G. Photographer Sabelo Mlangeni is immersed in his art. Sunday Times, South Africa [online] (published 10 June 2018).

2018 Edwards, C. New photography exhibition features South Africa’s flourishing Zionist churches. The South African, South Africa [online] (published 8 June 2018).

2018 Elizabeth, M. Sabelo Mlangeni // capturing the confidence and intimacy of LGBTQ communities in South Africa. Bubblegum Club, South Africa [online] (published 5 March 2018).

2017 Madondo, B. SABELO MLANGENI: BIG CITY. Aperture.

2017 Madondo, B. A South African Flâneur’s Ambivalent View of Johannesburg. The New Yorker, US [online] (published 4 June 2017).

2017 Keam, S. Sabelo Mlangeni: Documenting A New South Africa. The Culture Trip, UK [online] (published 11 January 2017).

2014 Corrigall, M. Beyond Trauma: Landscape, Memory, and Agency in Photographs by Cedric Nunn and Sabelo Mlangeni. Safundi. 15(2-3): 329–351.

2014 Ngcobo, G. Art in Context Africa, Part I: Sabelo Mlangeni’s No Problem, and a visit to the site of Michelle Monareng’s Removal to Radium. Art Review, UK (published October 2014).

2012 Bongela, M. Vanity, Pride and Prejudice. Mail & Guardian, South Africa [online] (published 10 February 2012).

2010 Jacobs, S. ‘Afropolis’. Africa is a Country, US [online] (published 13 November 2010).

2009 Jacobs, S. Photography: Sabelo Mlangeni. Africa is a Country, US [online] (published 11 September 2009).

2024 Dunster, F. & Gordon, T. Photography - A Queer History. Ilex, UK.

2023 Bonsu, O. A World in Common: Contemporary African Photography. Tate publishing (published July 2023).

2022 Bonsu, O. African Art Now: 50 Pioneers Defining African Art for the Twenty-First Century. Chronicle Books LLC / Tate, UK.

2022 Balogun, E. et al. Isivumelwano. Fw:Books, Amsterdam (published May 2022).

2022 Allen, S. Tate Photography Series: Sabelo Mlangeni. Tate Publishing (published May 2022).

2021 Underwood, J. L. & Okeke-Agulu, C et al. African Artists: From 1882 to Now. Phaidon Press, UK. Published 17 November 2021.

2019 Cane, J. Civilising Grass: The art of the lawn on the South African Highveld. NYU Press, US.

2018 Sabelo Mlangeni: Umlindelo wamaKholwa. Wits Art Museum, South Africa.

2011 Sabelo Mlangeni: At Home / Ghost Towns. Michael Stevenson, South Africa.

2010 Sabelo Mlangeni: Country Girls. Michael Stevenson, South Africa.

2009 Sabelo Mlangeni: Men Only. Michael Stevenson, South Africa.

— selected press

2025 O’Toole, S. Sabelo Mlangeni. Artforum [online] (published September 2025).

2025 Chepape, L. Looking back in black and white to see more clearly [online] (published April 2025).

2024 Sincuba, T. Kamogelo Walaza on Curating Sabelo Mlangeni’s Solo “Ngiyabona Phambili” [online] (published September 2025).

2024 Littlewood, C. Collective (un)doings. Photomonitor: [online] (published January 2024).

2024 Mendenhall-Dever, S. Q&A/ Visiting Artist Sabelo Mlangeni on photographing South African communities and identities. The Standford Daily [online] (published 09 January 2024).

2023 Tobin, K. Joy, tenderness and intimacy are celebrated by artists in London. Wallpaper [online] (published 23 December 2023).

2023 Bruno, G. How ‘Pictures of Us’ Channels the Universality of the Human Experience. ELEPHANT [online] (published 14 December 2023).

2023 Shinners, K. Common. e-flux [online] (published 22 June 2023).

2023 The meaning of work in the modern world: a photography special. Financial Times [online] (published 5 January 2023).

2022 Stretch to the limit! Images from the Tate collection – in pictures. The Guardian. [online] (published 18 May 2022)

2022 Nigeria: a royal house, persecuted LGBT refuge. Altus Intel. [online] (published 2 January 2022).

2021 Mavuso, T. & Mlangeni, S. Forgotten Spools: Looking Through the Archives of Cynthia Mavuso. Mail & Guardian. [online] (published 1 October 2021).

2021 Stevens, N. ‘Photographs In Our Mother Tongue’: The new South Africa under scrutiny’. Mail and Guardian [online] (published 10 May 2021).

2021 Nkomo, V. History is happening: ‘The thing itself exists everywhere’ at blank projects. ArtThrob [online] (published 23 March 2021).

2020 Dinsdale. E. Sabelo Mlangeni’s moving photos of life inside a Nigerian queer safe house. Dazed [online] (published 29 September 2020).

2020 Moloi, N. Against erasure and forgetting: Sabelo Mlangeni and Igshaan Adams at blank projects. ArtThrob [online] (published 11 February 2020).

2020 Collison, C. Sabelo Mlangeni’s intimate portrayal of queer Nigeria. New Frame [online] (7 February 2020).

2018 Sabelo Mlangeni Exhibition on Zion Churches shows in Johannesburg. Afropolitian Explosive, South Africa [online] (published 8 December 2018).

2018 Confessional Documentary: Sabelo Mlangeni and Wolfgang Tillmans in Johannesburg. ArtThrob, South Africa [online] (published 26 October 2018).

2018 Seymour, T. Sabelo Mlangeni. Nataal, UK [online] (published 11 October 2018).

2018 Warner, M. Sabelo Mlangeni’s images of South Africa. British Journal of Photography, UK [online] (published 5 October 2018).

2018 Mcutha, N. Umlindelo wamaKholwa: Sabelo Mlangeni’s zionism photography. Between 10 and 5, South Africa [online] (published 26 July 2018).

2018 Stevens, N. The Believers: Sabelo Mlangeniʼs ‘Umlindelo wamaKholwaʼ. ArtThrob, South Africa [online] (published 17 July 2018).

2018 Lim, D. Quiet images of the Zionist Christian Church. City Press, South Africa [online] (published 8 July 2018).

2018 Anstey, G. Photographer Sabelo Mlangeni is immersed in his art. Sunday Times, South Africa [online] (published 10 June 2018).

2018 Edwards, C. New photography exhibition features South Africa’s flourishing Zionist churches. The South African, South Africa [online] (published 8 June 2018).

2018 Elizabeth, M. Sabelo Mlangeni // capturing the confidence and intimacy of LGBTQ communities in South Africa. Bubblegum Club, South Africa [online] (published 5 March 2018).

2017 Madondo, B. SABELO MLANGENI: BIG CITY. Aperture.

2017 Madondo, B. A South African Flâneur’s Ambivalent View of Johannesburg. The New Yorker, US [online] (published 4 June 2017).

2017 Keam, S. Sabelo Mlangeni: Documenting A New South Africa. The Culture Trip, UK [online] (published 11 January 2017).

2014 Corrigall, M. Beyond Trauma: Landscape, Memory, and Agency in Photographs by Cedric Nunn and Sabelo Mlangeni. Safundi. 15(2-3): 329–351.

2014 Ngcobo, G. Art in Context Africa, Part I: Sabelo Mlangeni’s No Problem, and a visit to the site of Michelle Monareng’s Removal to Radium. Art Review, UK (published October 2014).

2012 Bongela, M. Vanity, Pride and Prejudice. Mail & Guardian, South Africa [online] (published 10 February 2012).

2010 Jacobs, S. ‘Afropolis’. Africa is a Country, US [online] (published 13 November 2010).

2009 Jacobs, S. Photography: Sabelo Mlangeni. Africa is a Country, US [online] (published 11 September 2009).

blank is pleased to present Honeymoon. The happily ever after?, a solo exhibition by Sabelo Mlangeni (b.1980, Driefontein) and his third with the gallery.

Developed over the past five years, Honeymoon. The happily ever after? is the artist’s latest body of work, inspired by a honeymoon trip to eThekwini (Durban) following the release of his wedding documentary series, Isivumelwano. This series interrogates the notion of ‘happily ever after’, and the problematics or shortcomings of such a concept within the context of the contemporary South African experience. Divided into multiple chapters, the series serves as a portrait of the tropical seaside city of eThekwini, captured by Mlangeni in all its glamour and decay. Despite being the country’s third largest metropolis and its largest port of trade, eThekwini has been marred by years of political instability and neglect, environmental disaster and infrastructural collapse.

Mlangeni’s photographs present an intimate account of eThekwini’s multifaceted life: smiling portraits of musclebound men and women and pleasure-seeking beachgoers are juxtaposed with images of the fallout from two of the most violent events in recent South African history - the floods of 2022 and the riots of 2021 - both of which cost hundreds of lives and brought the city to its knees. A fifth chapter in the series documents the iconic architectural heritage of the South Beach area, languishing in a state of semi-disrepair. Exhibited for the first time, Honeymoon. Happily ever after? testifies to the broken promise of South Africa in the post-democratic era and the society that thrives in spite of it.

Developed over the past five years, Honeymoon. The happily ever after? is the artist’s latest body of work, inspired by a honeymoon trip to eThekwini (Durban) following the release of his wedding documentary series, Isivumelwano. This series interrogates the notion of ‘happily ever after’, and the problematics or shortcomings of such a concept within the context of the contemporary South African experience. Divided into multiple chapters, the series serves as a portrait of the tropical seaside city of eThekwini, captured by Mlangeni in all its glamour and decay. Despite being the country’s third largest metropolis and its largest port of trade, eThekwini has been marred by years of political instability and neglect, environmental disaster and infrastructural collapse.

Mlangeni’s photographs present an intimate account of eThekwini’s multifaceted life: smiling portraits of musclebound men and women and pleasure-seeking beachgoers are juxtaposed with images of the fallout from two of the most violent events in recent South African history - the floods of 2022 and the riots of 2021 - both of which cost hundreds of lives and brought the city to its knees. A fifth chapter in the series documents the iconic architectural heritage of the South Beach area, languishing in a state of semi-disrepair. Exhibited for the first time, Honeymoon. Happily ever after? testifies to the broken promise of South Africa in the post-democratic era and the society that thrives in spite of it.

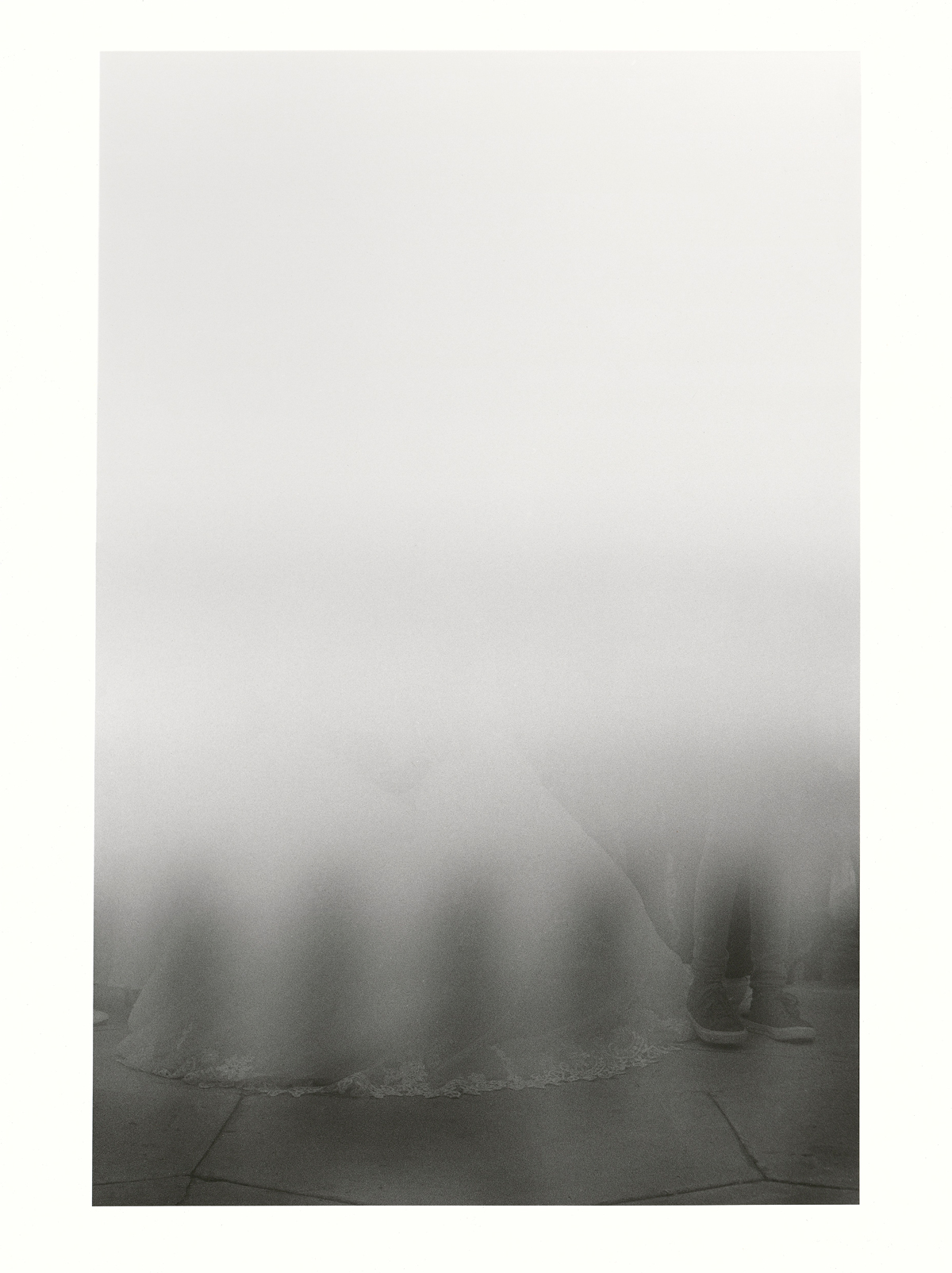

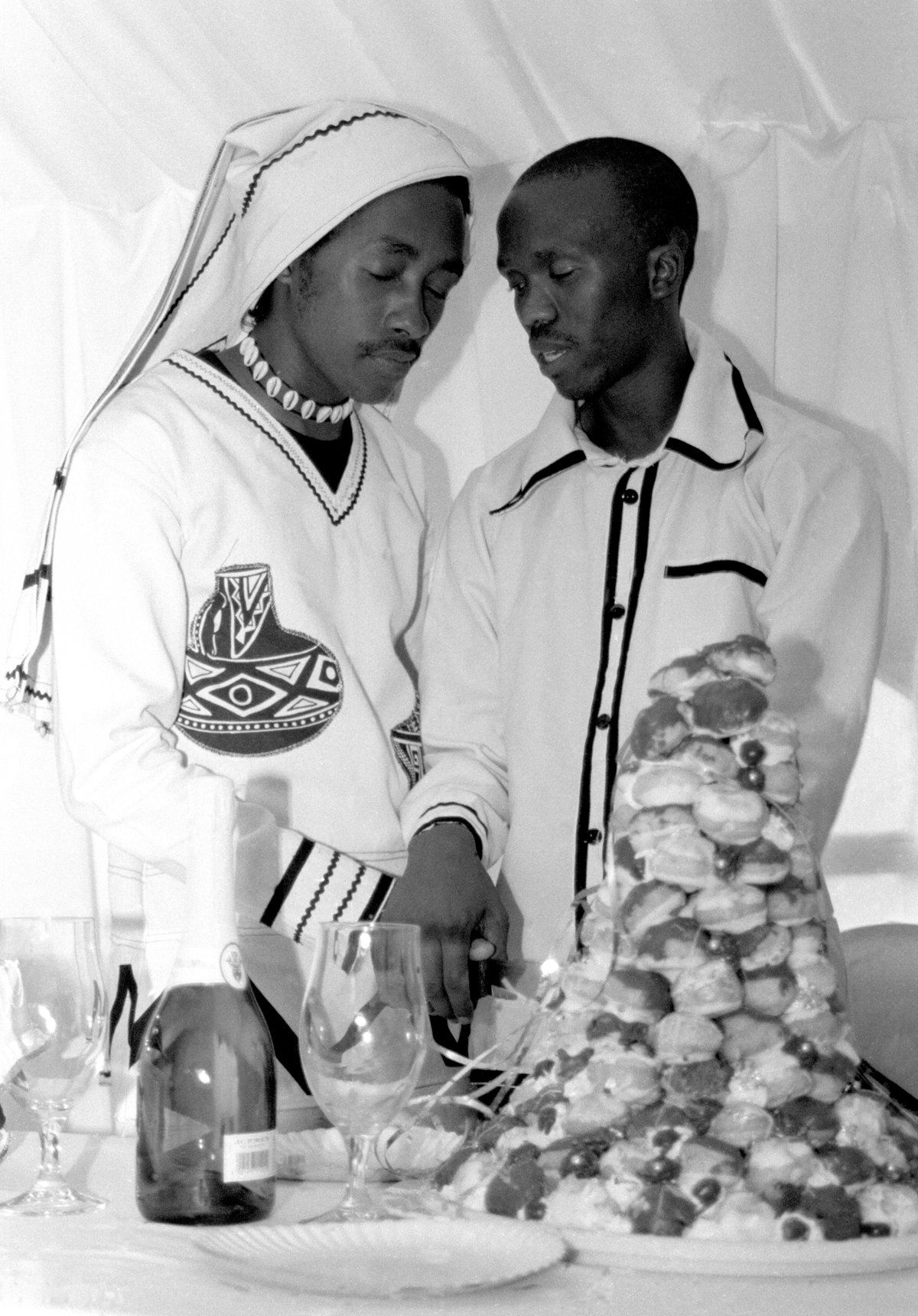

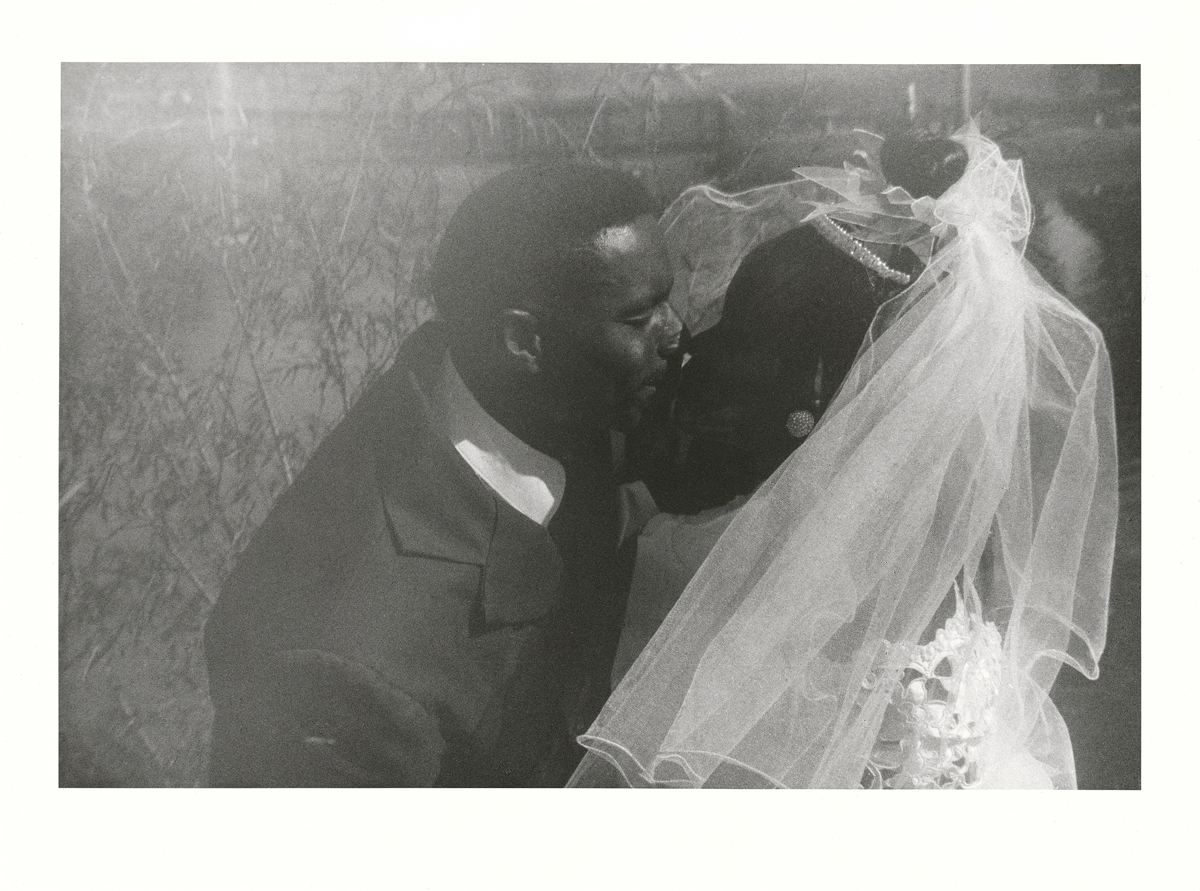

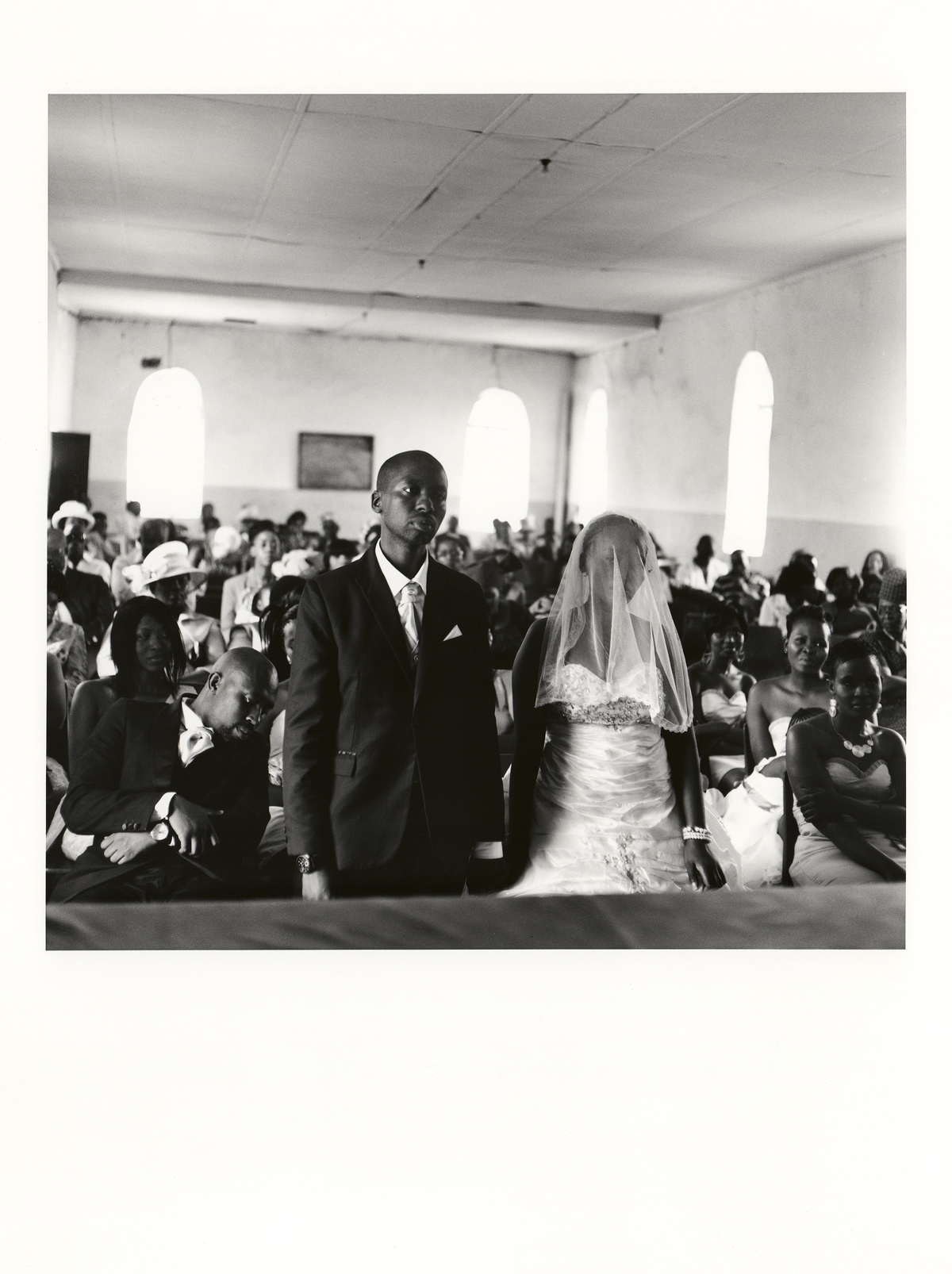

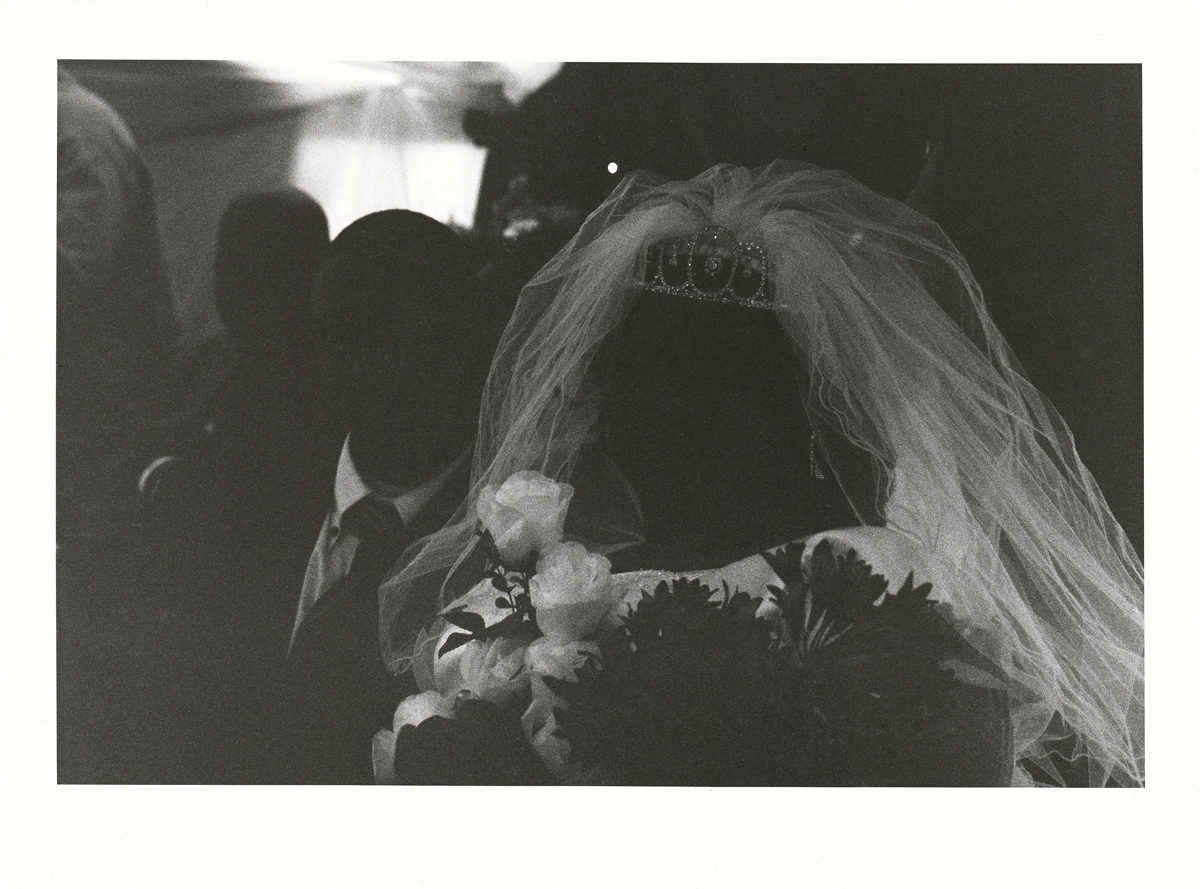

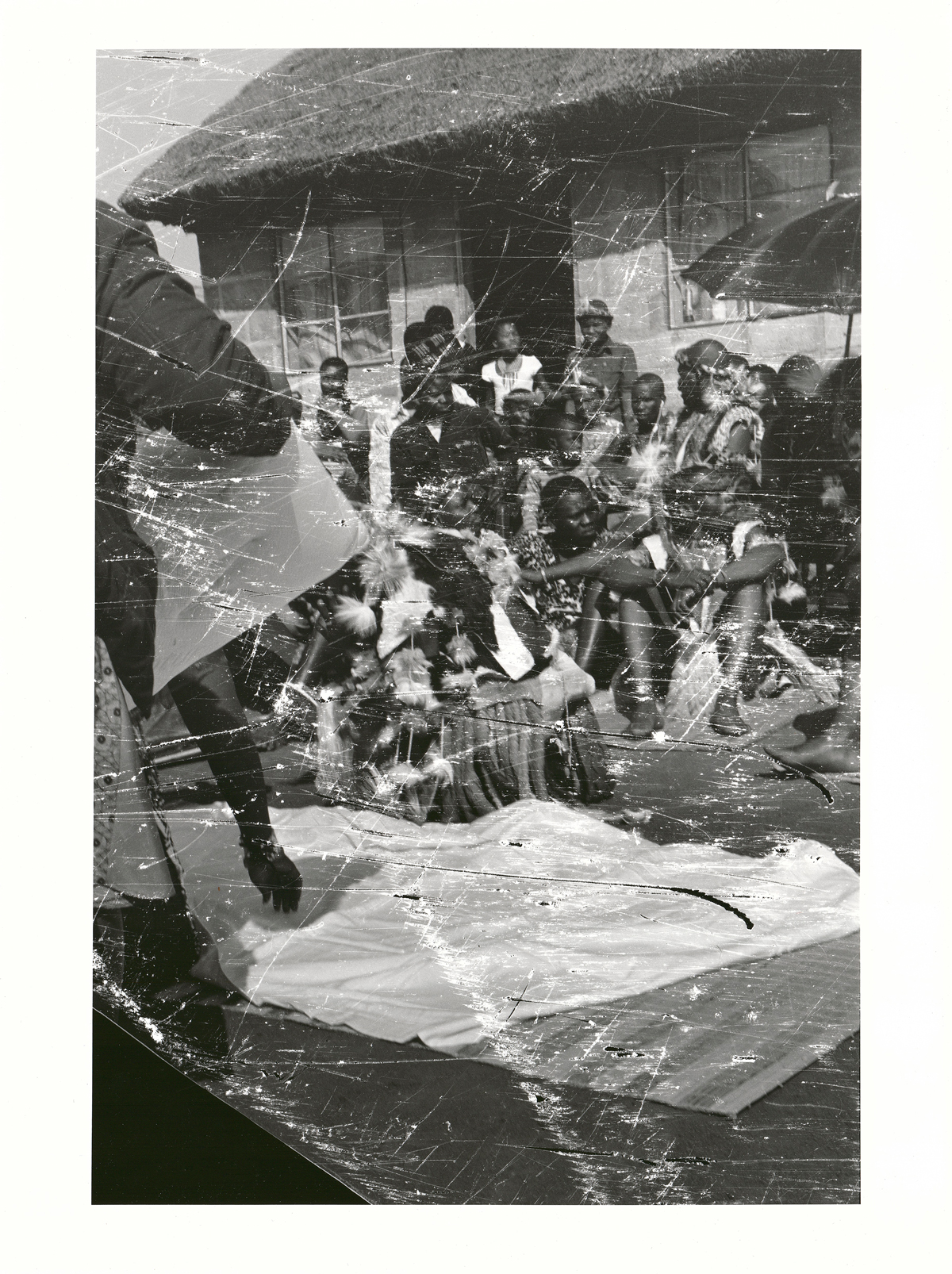

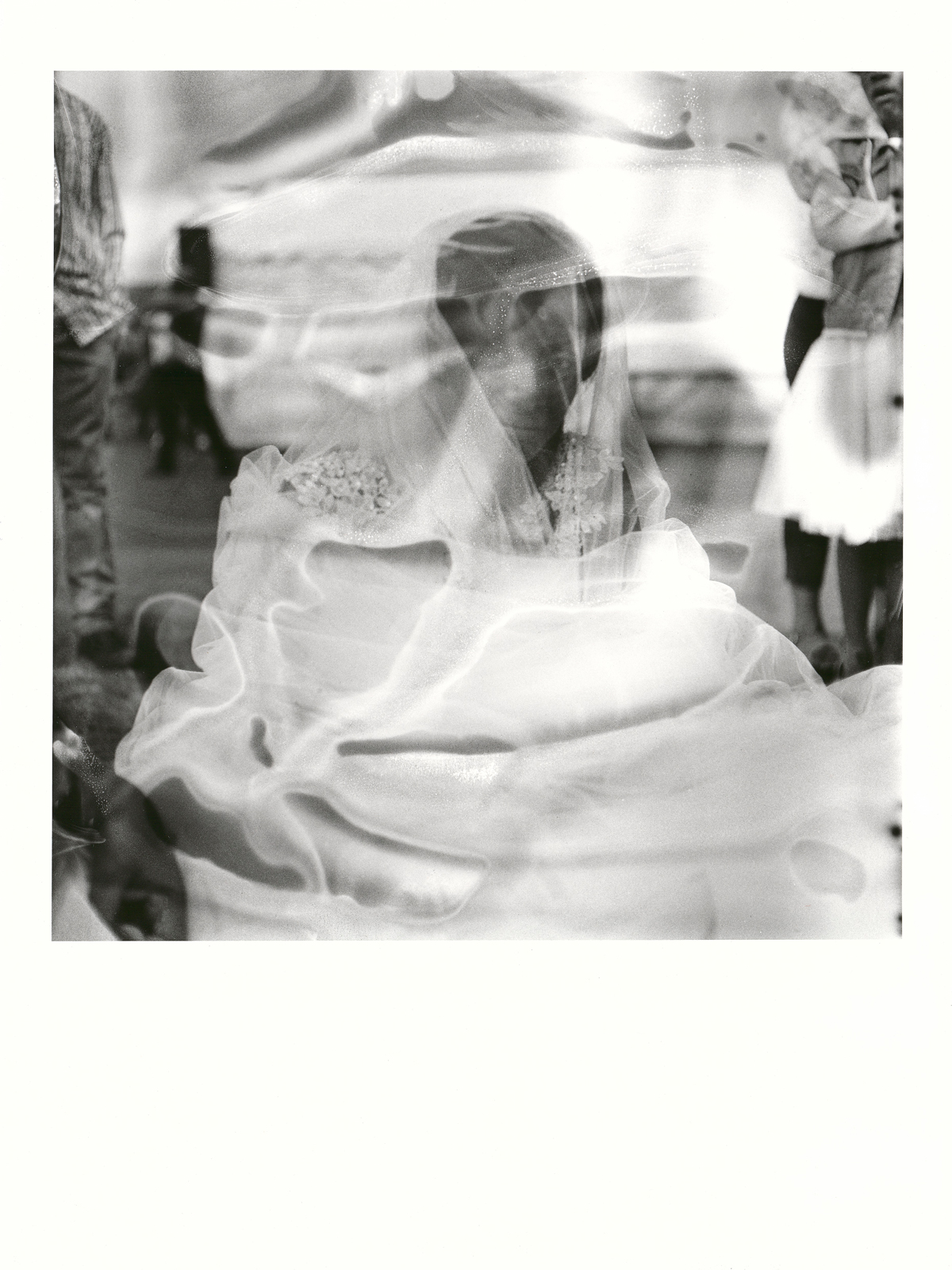

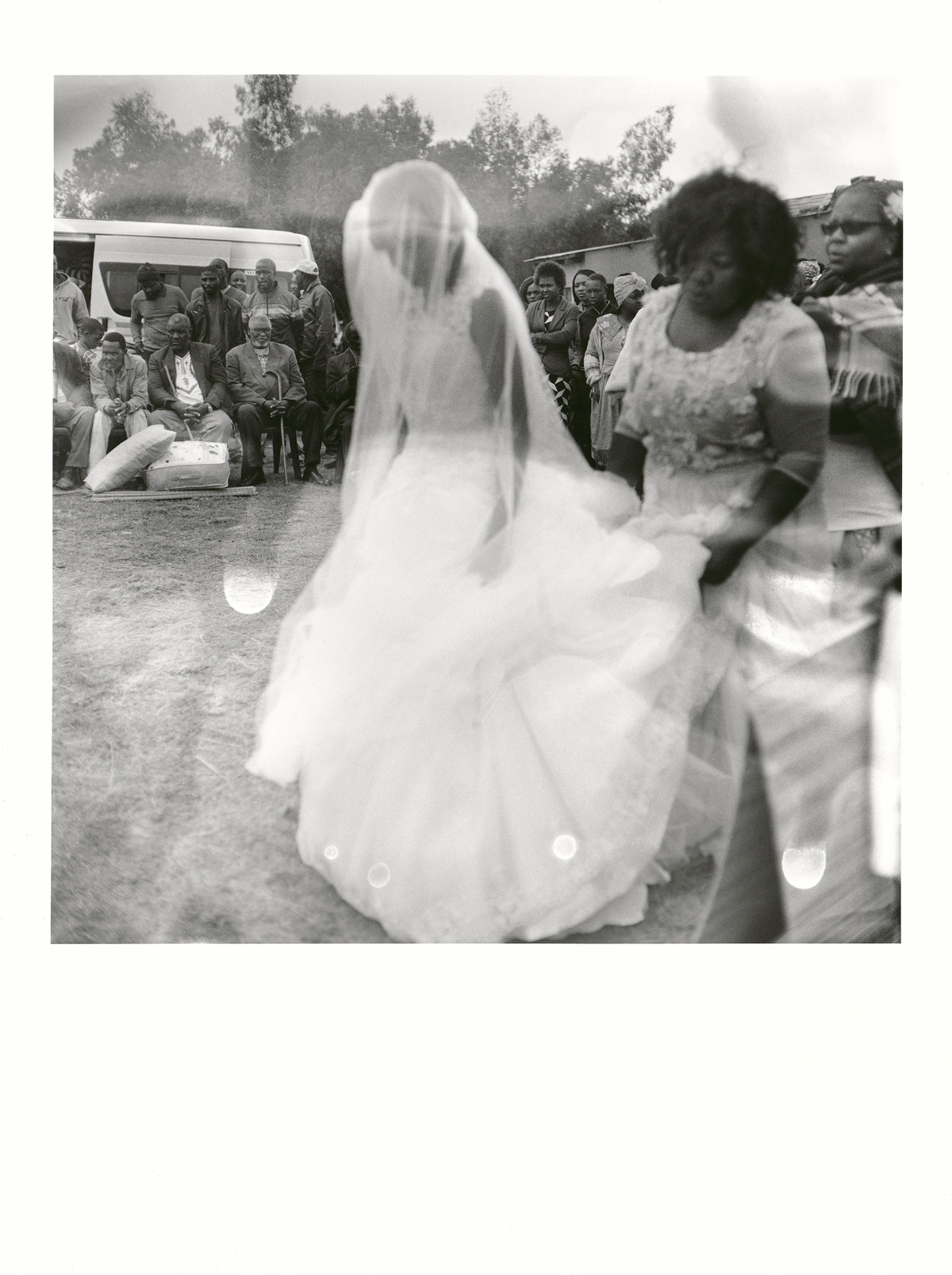

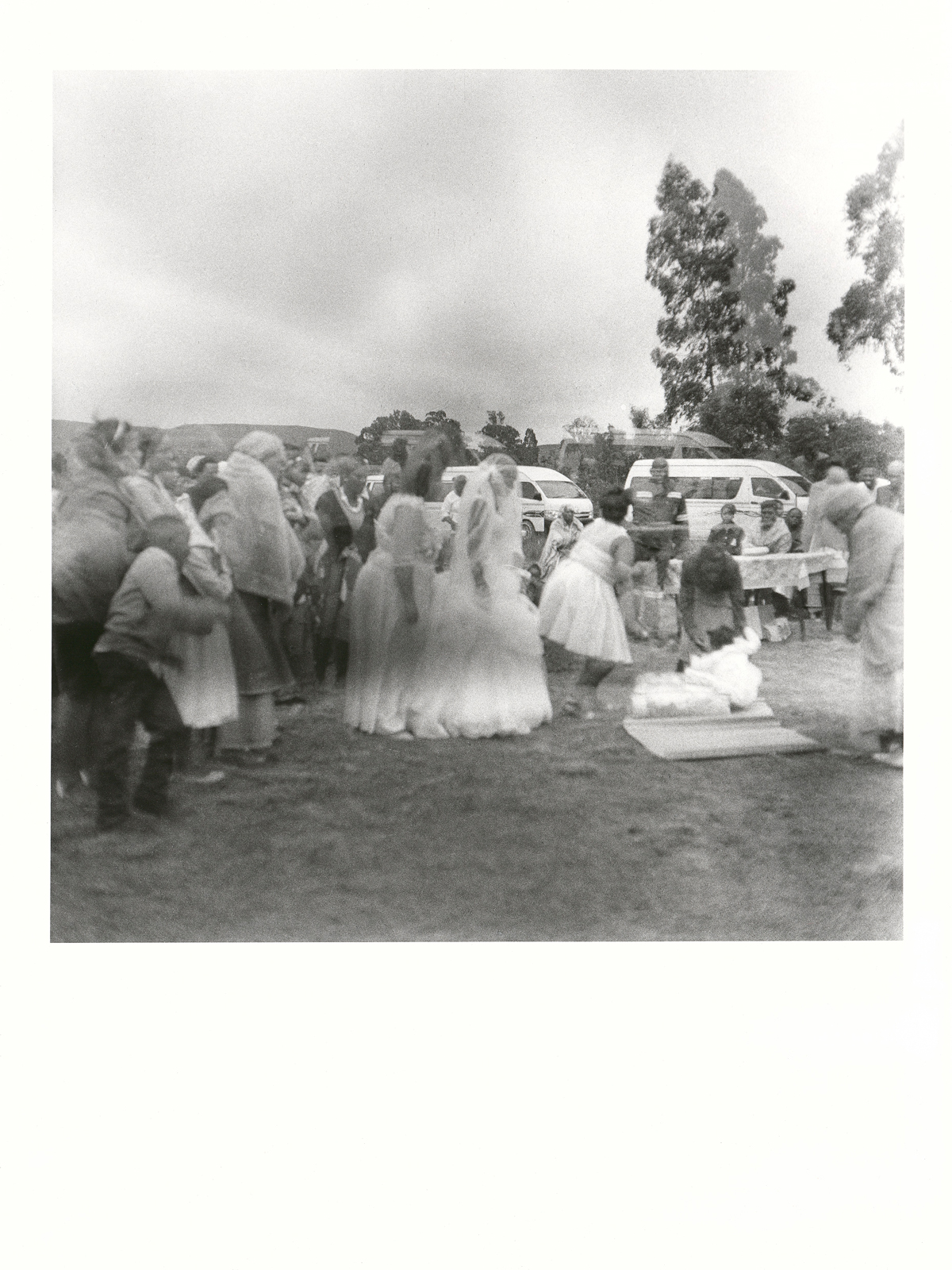

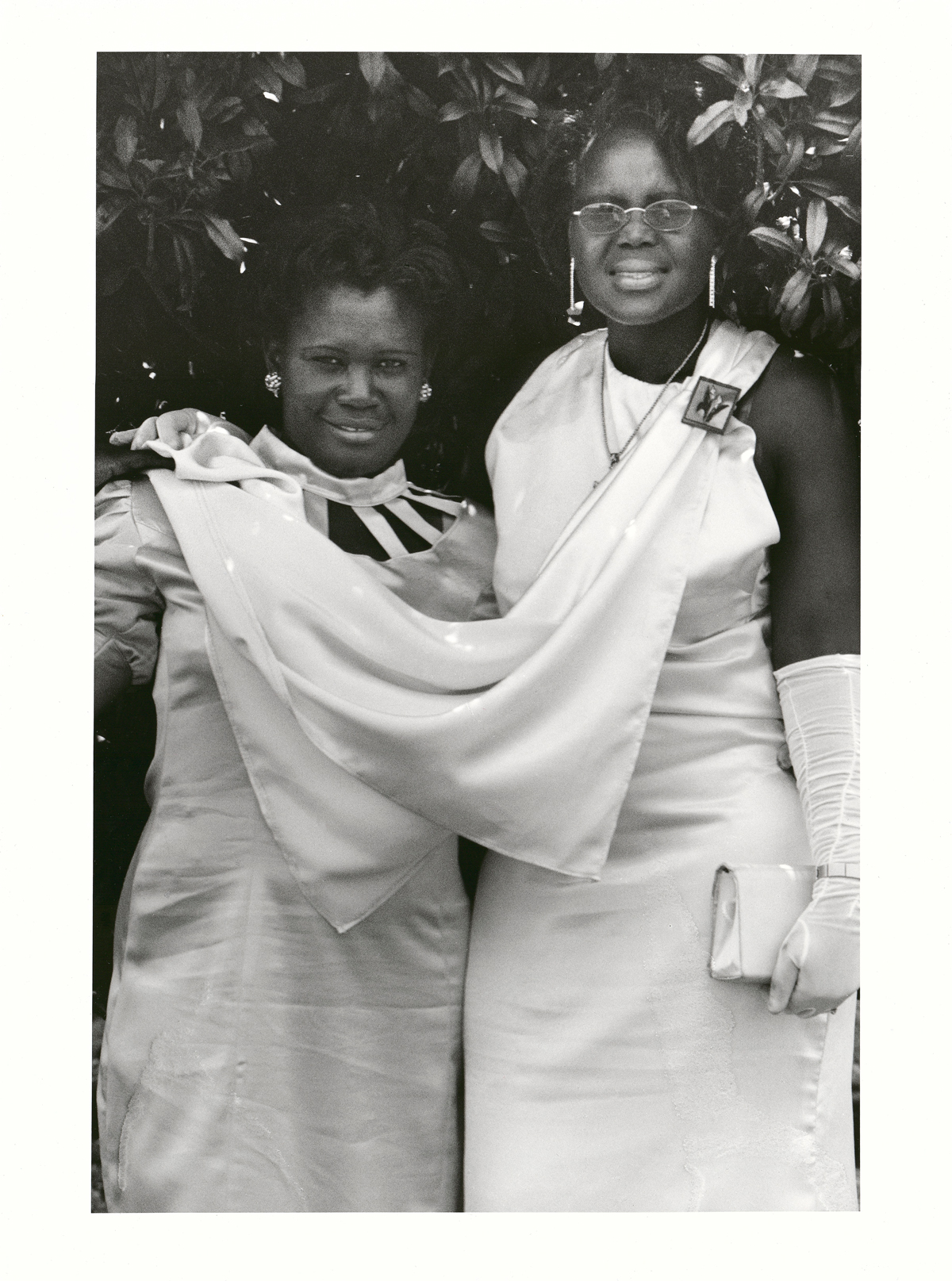

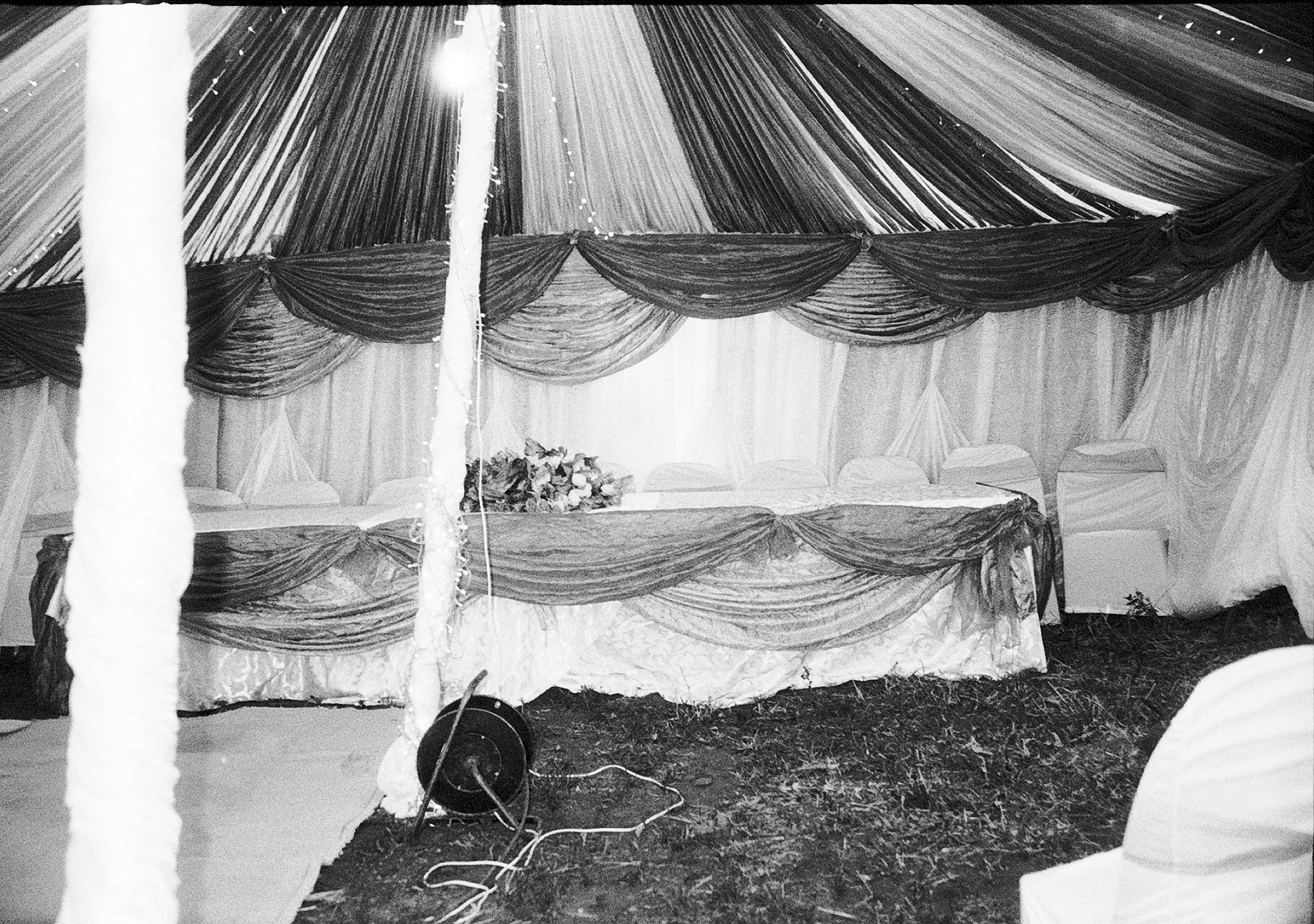

The Nguni word, isivumelwano, represents a contract, agreement or alliance. In Sabelo Mlangeni's context, Isivumelwano is a cause for celebration and critique of the relationships we keep with others. Reflecting on previously unseen works that date back nearly 30 years, the South African photographer describes his work as magnifying 'the systems we exist in (and against).'

As an excavated body (politic) of images, Isivumelwano draws time back to life in South Africa from 1994: a critical time for coexistence. The year marked a turning point for communities in the dark; generations - broken, Black - witnessed the cogs turn for freedom from the homelands. After a series of struggles, South Africa became a country that gave rise to Black majority rule: Amandla (power).

Like a ceremonial shroud obscuring brutality in black and white, Mlangeni's photographic critique of the histories of injustice hangs high - yet is in no way direct. Instead, the series communicates a conscious act of social cohesion, reinforcing a pattern of power that is truly affirming: love.

As the American author, feminist, and social activist bell hooks understood, expressing love to one another is the ultimate practice of freedom: 'ours is a shared struggle... we are each other's fate'. Mlangeni's photographs of wedding ceremonies among Black communities in Southern African sites such as KwaZulu-Natal, Alexandria township, and the artists' hometown of Driefontein, record sacred moments throughout the marriage process. The camera’s intervention magnifies the ritual of love as a formal act that drives cultures from subjugation to celebration. As a political unifier, the contract - love - becomes a force of liberation.

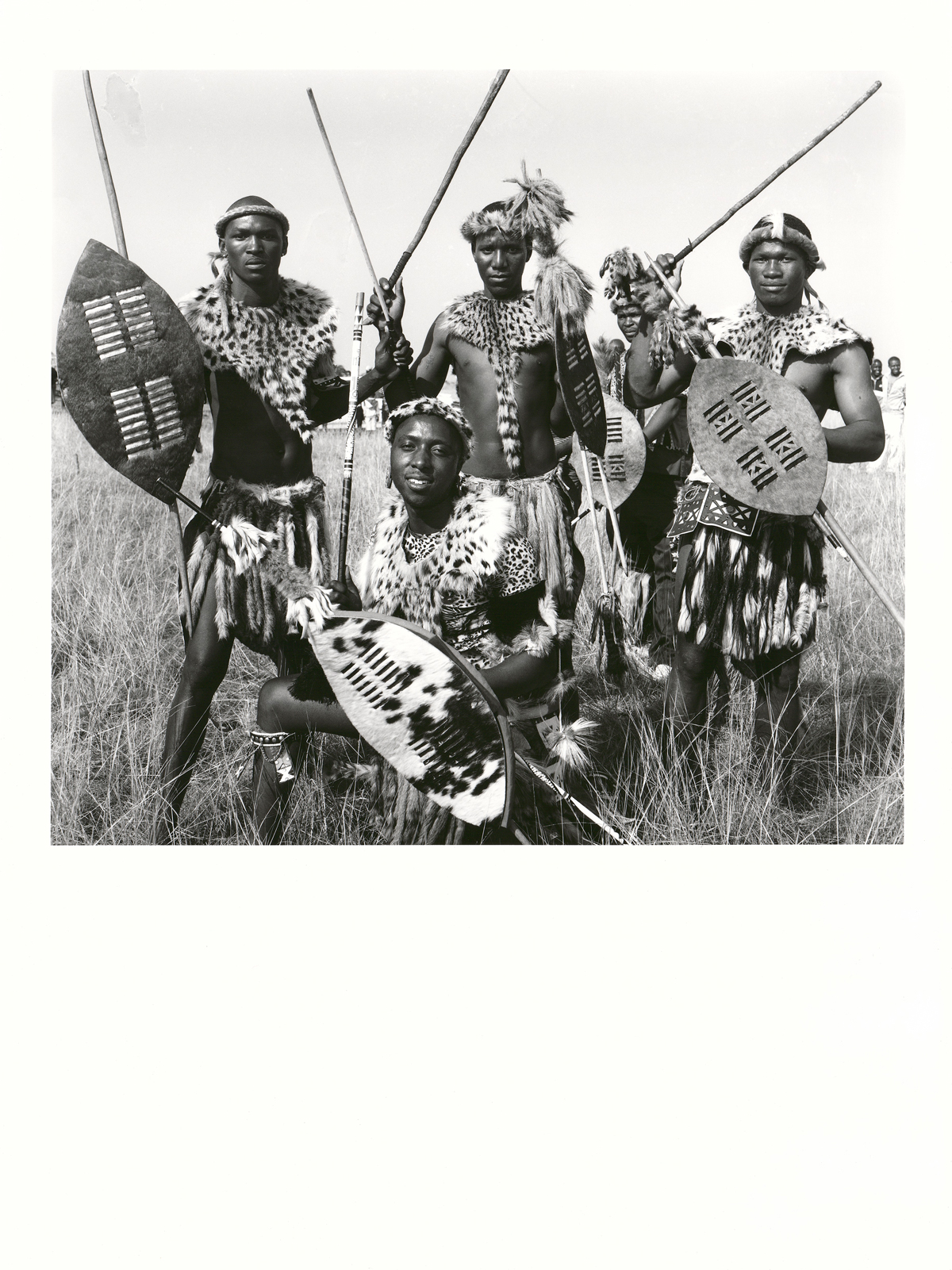

In his survey of nuptials, the artist captures multiple stories of the bride, her groom and clansmen. Celebrants travel far and wide to bear witness, hold court and serve in their function, while others are framed bearing the heavy load of the heart, or bearing foodstuffs foraged, customary artefacts, and cattle reared for the cause.

Unions held in churches, community halls, wild grasslands, and in the shadows, upend inherited notions of the white wedding. The spectator is invited to observe Mlangeni's delicate definition of love, with a nod to subversive sexual orientations and the precariousness of gender-based roles.

The significance of material culture - from the wedding cake - to Black folk goodly garbed in Western wears – is laid bare. Speaking plainly through images that teem with pride, the photographer's elegant service to unions is a stoic reminder of those who have stolen our hearts.

Mlangeni's Isivumelwano marks the covenant to spirits silenced - it speaks to people and places that hold hearts bound. Isivumelwano is a testament to the workings of love, which involves many and is often a tale of how it is denied - despite being owed to all.

Many of us who see these works have never known the scent of love, yet unyielding yearn for its ways, irrespective of whether it will last or lose.

Text by Emmanuel Balogun

As an excavated body (politic) of images, Isivumelwano draws time back to life in South Africa from 1994: a critical time for coexistence. The year marked a turning point for communities in the dark; generations - broken, Black - witnessed the cogs turn for freedom from the homelands. After a series of struggles, South Africa became a country that gave rise to Black majority rule: Amandla (power).

Like a ceremonial shroud obscuring brutality in black and white, Mlangeni's photographic critique of the histories of injustice hangs high - yet is in no way direct. Instead, the series communicates a conscious act of social cohesion, reinforcing a pattern of power that is truly affirming: love.

As the American author, feminist, and social activist bell hooks understood, expressing love to one another is the ultimate practice of freedom: 'ours is a shared struggle... we are each other's fate'. Mlangeni's photographs of wedding ceremonies among Black communities in Southern African sites such as KwaZulu-Natal, Alexandria township, and the artists' hometown of Driefontein, record sacred moments throughout the marriage process. The camera’s intervention magnifies the ritual of love as a formal act that drives cultures from subjugation to celebration. As a political unifier, the contract - love - becomes a force of liberation.

In his survey of nuptials, the artist captures multiple stories of the bride, her groom and clansmen. Celebrants travel far and wide to bear witness, hold court and serve in their function, while others are framed bearing the heavy load of the heart, or bearing foodstuffs foraged, customary artefacts, and cattle reared for the cause.

Unions held in churches, community halls, wild grasslands, and in the shadows, upend inherited notions of the white wedding. The spectator is invited to observe Mlangeni's delicate definition of love, with a nod to subversive sexual orientations and the precariousness of gender-based roles.

The significance of material culture - from the wedding cake - to Black folk goodly garbed in Western wears – is laid bare. Speaking plainly through images that teem with pride, the photographer's elegant service to unions is a stoic reminder of those who have stolen our hearts.

Mlangeni's Isivumelwano marks the covenant to spirits silenced - it speaks to people and places that hold hearts bound. Isivumelwano is a testament to the workings of love, which involves many and is often a tale of how it is denied - despite being owed to all.

Many of us who see these works have never known the scent of love, yet unyielding yearn for its ways, irrespective of whether it will last or lose.

Text by Emmanuel Balogun

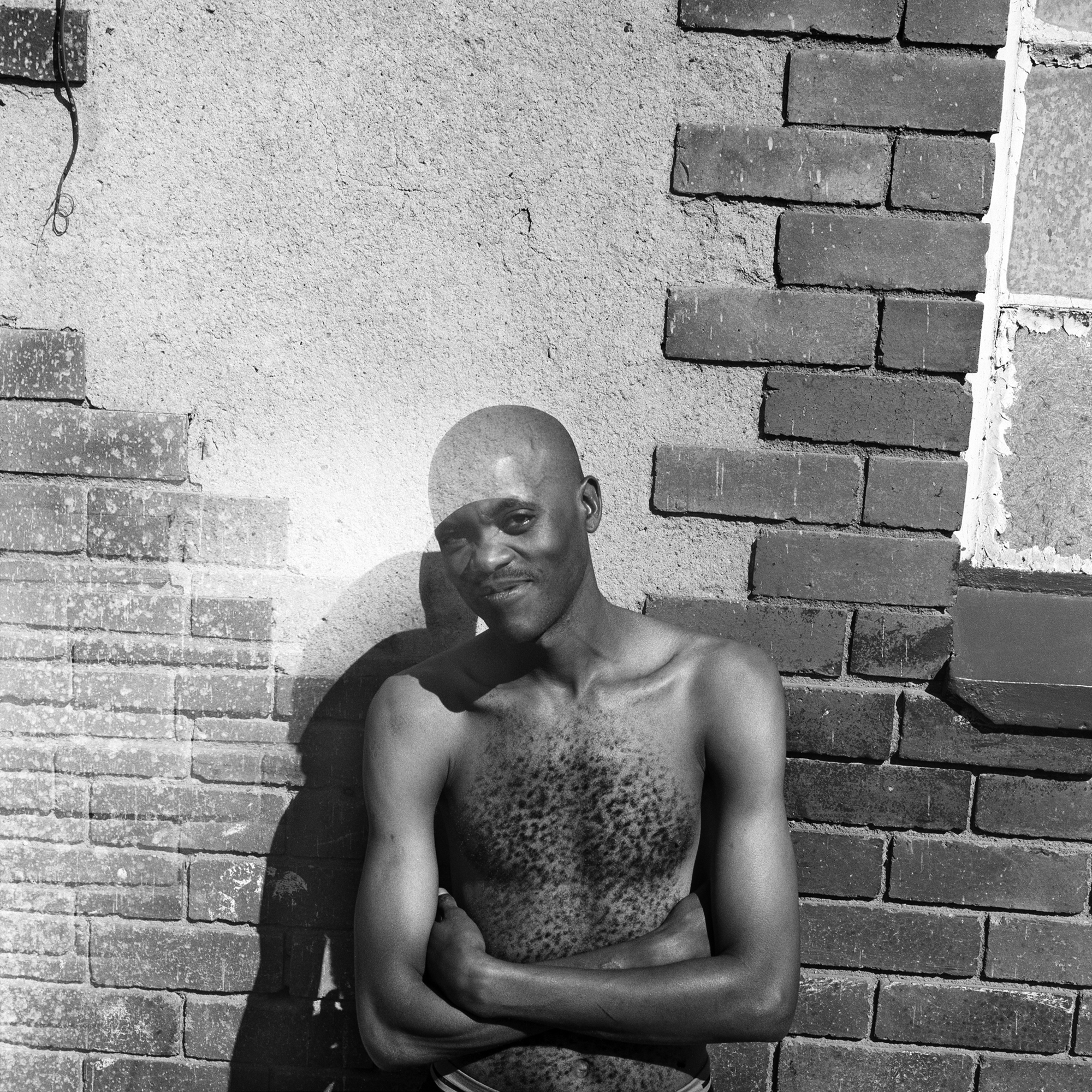

Like many cities in the world Lagos is a city of extremes. Individuals who fit into the mould of heteronormativity (especially those protected by wealth) are considered worthy of protection and celebration while others (feminised, queer and poor bodies) are rendered invisible and unworthy. Queer and poor people are not only invisible, they are also unsafe due to discrimination, criminalization and violence.

“The Royal House of Allure” is a name of a (safe) House on mainland Lagos where members of the queer community in need of boarding (due to various circumstances) live together. A House is a family unit that one is able to select into; a place of gathering for those who are not allowed to gather anywhere else. Houses are more than just places of survival, they are a physical embodiment of radical queer expression that encourage solidarity. House culture originates from New York’s ballroom culture which emerged in the 1920s and reached an apex in the 1980s — a matriarch, referred to as house mother, provides housing as well as a support system for members of the LGBTQIA+ community (referred to as her children). These establishments actively advocate for inclusivity and provide members of the community with a space to construct a sense of self through artistic practices within beauty, fashion and music.

In 2019, Mlangeni spent six weeks in Lagos photographing the queer community at The Royal House of Allure. His awareness of the House came as a result of interactions with well-known queer figures in Nigeria, through social media. This photographic essay forms part of a larger body of work photographing queer communities on the continent (specifically South Africa and the DRC).

The Royal House of Allure contains simple images that reveal the complexities behind representation. The images diverge at a single specific point; those that display fantasy through glamour where subjects actively pose for the camera and those that offer quieter banal moments where subjects are simply going on about their day at the house: braiding each other’s hair, having conversations, sewing clothes, napping, cooking, laughing and taking selfies. They offer us a glimpse of the love and acceptance between community members within the social structure of a House.

John Berger saw glamour as a modern invention linked to ideas of grace, elegance and authority but of course, glamour is also inextricably linked with visibility, notions of beauty and power —those who see themselves (and are seen) feel powerful while others are rendered unseeable and therefore unworthy. Although it seems so obvious that it might require no comment, representation matters and images have the potential to influence systems of thought, views and opinions. The idea that images have the potential to influence systems of thought goes a long way in explaining Mlangeni’s commitment towards documenting various communities in his practice. The Royal House of Allure forms part of his broader practise of (re)imaging and (re)imagining vulnerable bodies as safe, seen and worthy of protection and celebration.

The series was presented at the second Lagos Biennial (26 October–23 November 2019) alongside works by over forty local and international artists and artist collectives.

Text by Nkgopoleng Moloi

“The Royal House of Allure” is a name of a (safe) House on mainland Lagos where members of the queer community in need of boarding (due to various circumstances) live together. A House is a family unit that one is able to select into; a place of gathering for those who are not allowed to gather anywhere else. Houses are more than just places of survival, they are a physical embodiment of radical queer expression that encourage solidarity. House culture originates from New York’s ballroom culture which emerged in the 1920s and reached an apex in the 1980s — a matriarch, referred to as house mother, provides housing as well as a support system for members of the LGBTQIA+ community (referred to as her children). These establishments actively advocate for inclusivity and provide members of the community with a space to construct a sense of self through artistic practices within beauty, fashion and music.

In 2019, Mlangeni spent six weeks in Lagos photographing the queer community at The Royal House of Allure. His awareness of the House came as a result of interactions with well-known queer figures in Nigeria, through social media. This photographic essay forms part of a larger body of work photographing queer communities on the continent (specifically South Africa and the DRC).

The Royal House of Allure contains simple images that reveal the complexities behind representation. The images diverge at a single specific point; those that display fantasy through glamour where subjects actively pose for the camera and those that offer quieter banal moments where subjects are simply going on about their day at the house: braiding each other’s hair, having conversations, sewing clothes, napping, cooking, laughing and taking selfies. They offer us a glimpse of the love and acceptance between community members within the social structure of a House.

John Berger saw glamour as a modern invention linked to ideas of grace, elegance and authority but of course, glamour is also inextricably linked with visibility, notions of beauty and power —those who see themselves (and are seen) feel powerful while others are rendered unseeable and therefore unworthy. Although it seems so obvious that it might require no comment, representation matters and images have the potential to influence systems of thought, views and opinions. The idea that images have the potential to influence systems of thought goes a long way in explaining Mlangeni’s commitment towards documenting various communities in his practice. The Royal House of Allure forms part of his broader practise of (re)imaging and (re)imagining vulnerable bodies as safe, seen and worthy of protection and celebration.

The series was presented at the second Lagos Biennial (26 October–23 November 2019) alongside works by over forty local and international artists and artist collectives.

Text by Nkgopoleng Moloi

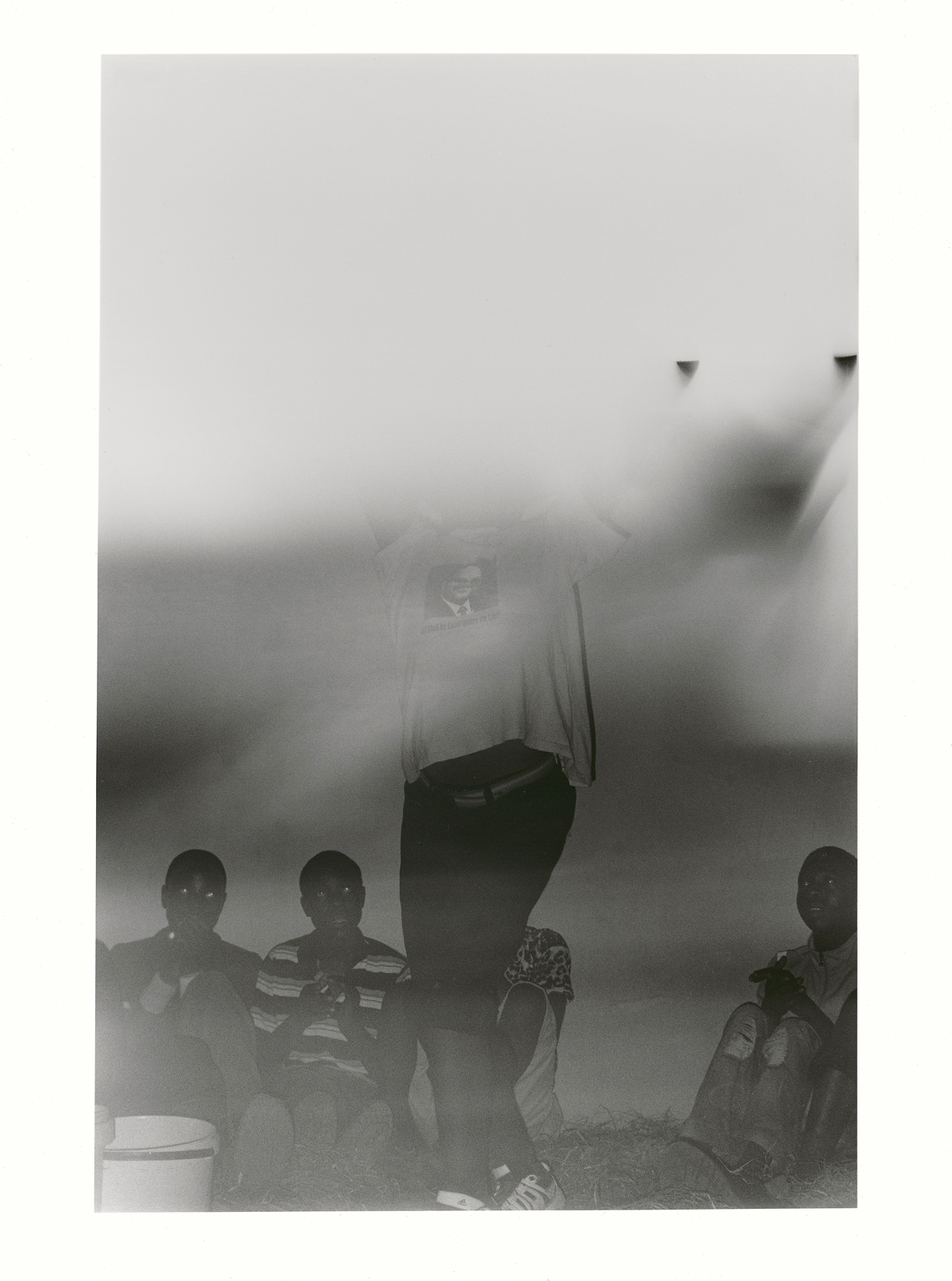

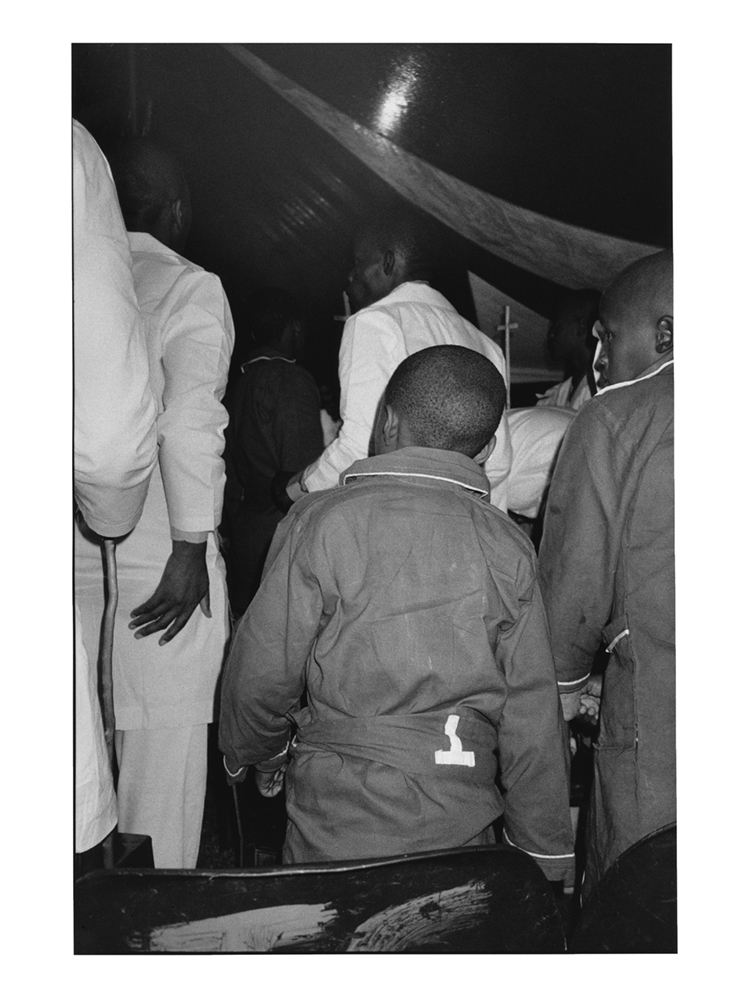

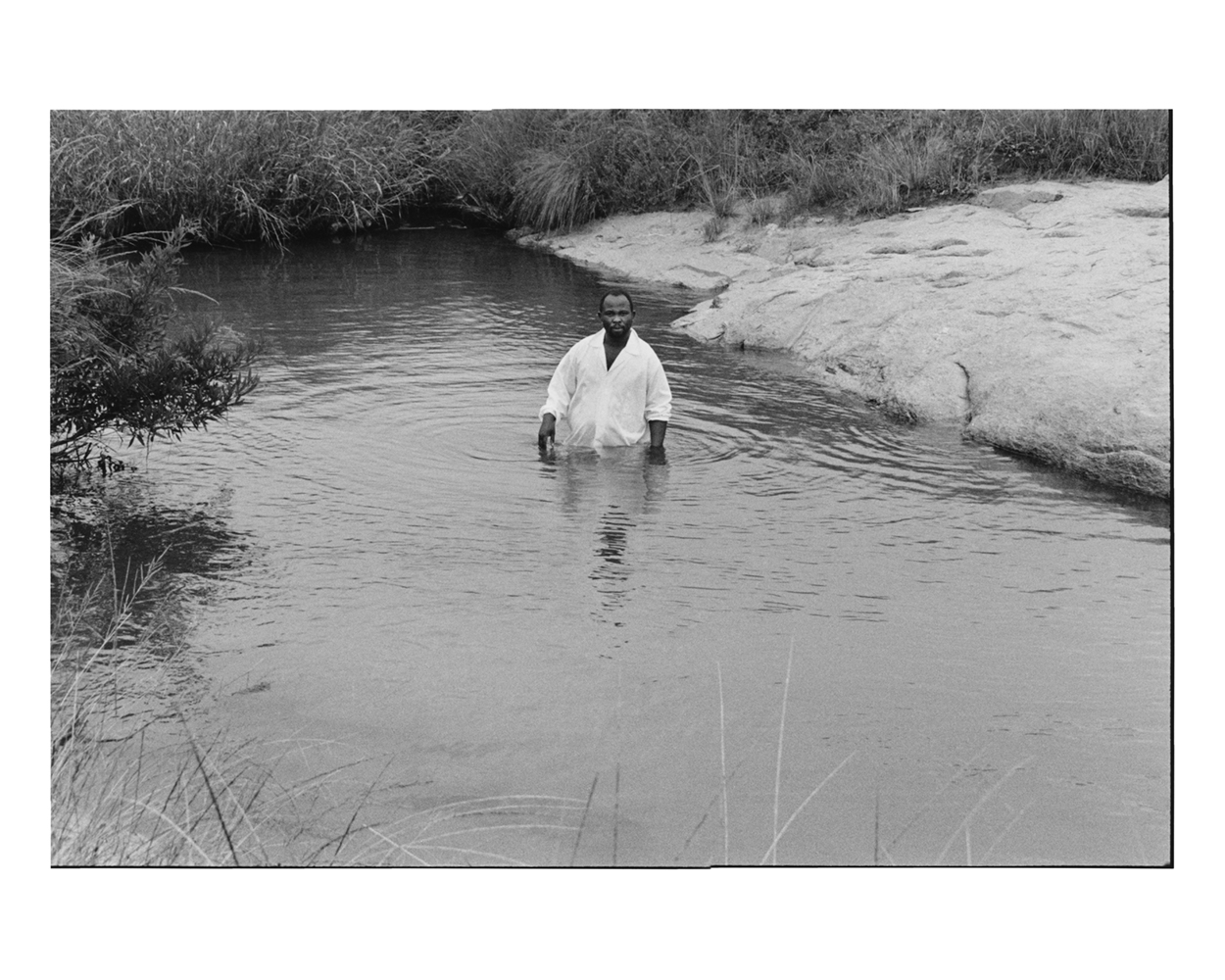

Umlindelo wamaKholwa explores the spiritual identity of those involved in two Zionist Churches in Johannesburg and Driefontein. The 20th Century Protestant faith healing movement, Zionism (unrelated to the Jewish

Zionism) is South Africa’s largest popular religious movement. Mlangeni, himself, is part of the Zionist Church and

has spent many years in its congregation. As with most of his series, his respectful place within the community

lifts the photographic boundaries of observer and subject, allowing him to capture authentic moments.

Within this body of work, Mlangeni focuses on the individuals and their relationships to belief; an experience of waiting is present. The title refers to a night-prayer vigil, where the community comes together to pray and stand in solidarity for awaiting spirits. In this time, friends are made and beliefs are supported: conveying how community is “forged through the experience of waiting together,” as the artist puts it, “In a way [that’s] parallel to the South African landscape: looking at what’s happening in this environment as a community of peoples.”

Within this body of work, Mlangeni focuses on the individuals and their relationships to belief; an experience of waiting is present. The title refers to a night-prayer vigil, where the community comes together to pray and stand in solidarity for awaiting spirits. In this time, friends are made and beliefs are supported: conveying how community is “forged through the experience of waiting together,” as the artist puts it, “In a way [that’s] parallel to the South African landscape: looking at what’s happening in this environment as a community of peoples.”

No Problem was photographed in Alexandra between 2011 and 2013, while the artist was a resident of the township. Alex, as it is known to locals, was founded before the Natives Land Act of 1913, and is one of the few urban areas in the country in which black Africans could own land under a freehold title during apartheid. Another anomaly is the township’s proximity to Sandton, a wealthy, leafy and mainly white suburb. Mlangeni straddled the two contrasting communities in a visual reflection on the realities of segregation and inequality, as well as issues of access for a visual documentarist. When in Sandton, he switched for the first time to colour, as if to mark visually the paradoxical distance between the two neighbourhoods.

As he says:

I have been moving around Johannesburg and its closest suburbs as someone interested in story-telling about everyday life. I am concerned by the migration flow within the urban areas, especially in the context of the South African social landscape, heavily burdened by legislation then, and now by economic constraints. I had experienced neither township life nor ‘Sandton life’ before, and while I was realising this essay I had to negotiate with the police and the locals my right to photograph public spaces, although with very different dynamics according to where I was.

In my early walks I found myself in many spaces where the situation and the living conditions were impossible to look at and to photograph: then I started wondering, what to frame? Soon another side of the hardships emerged, and I attempted to capture that hidden beauty, that ordinary peace.