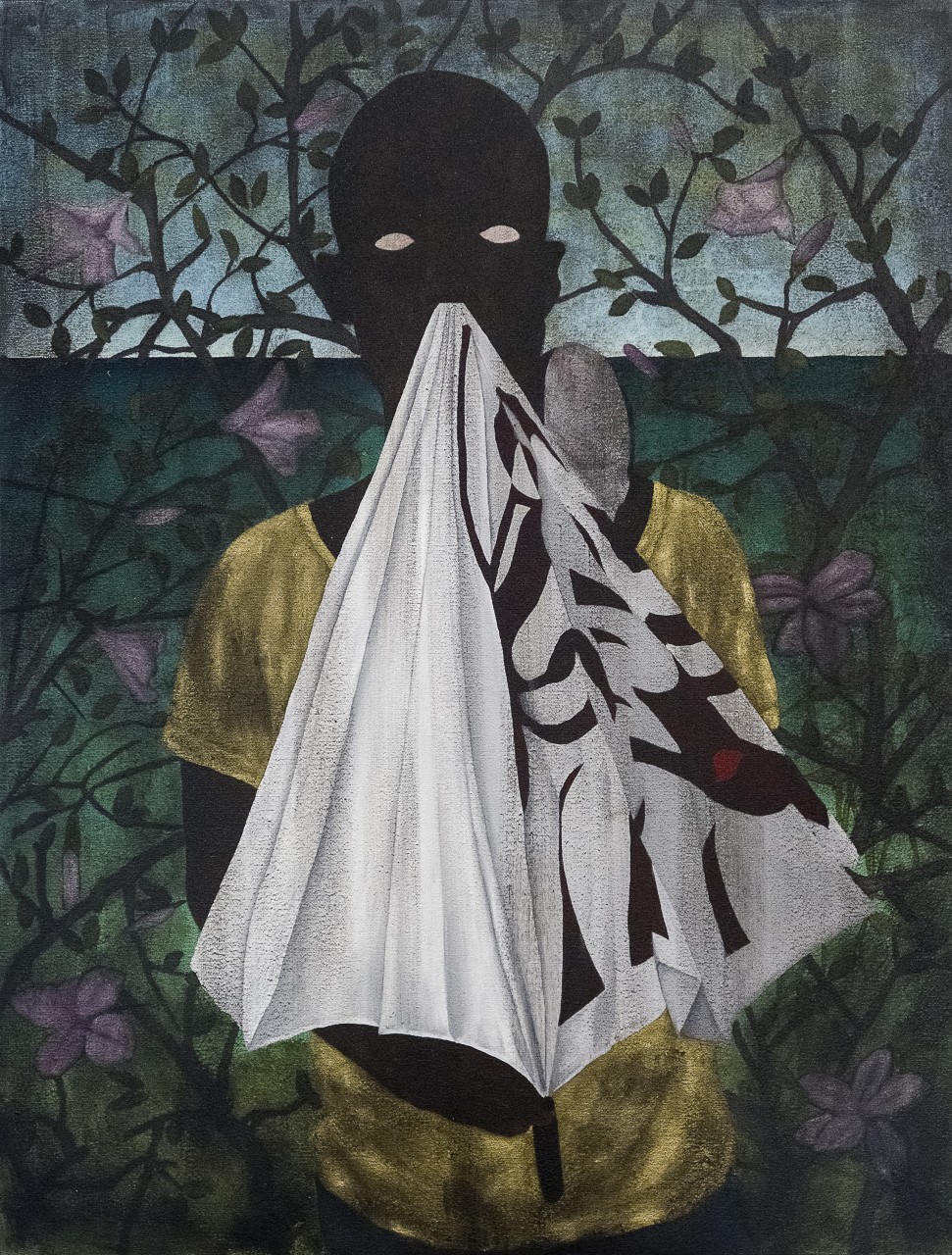

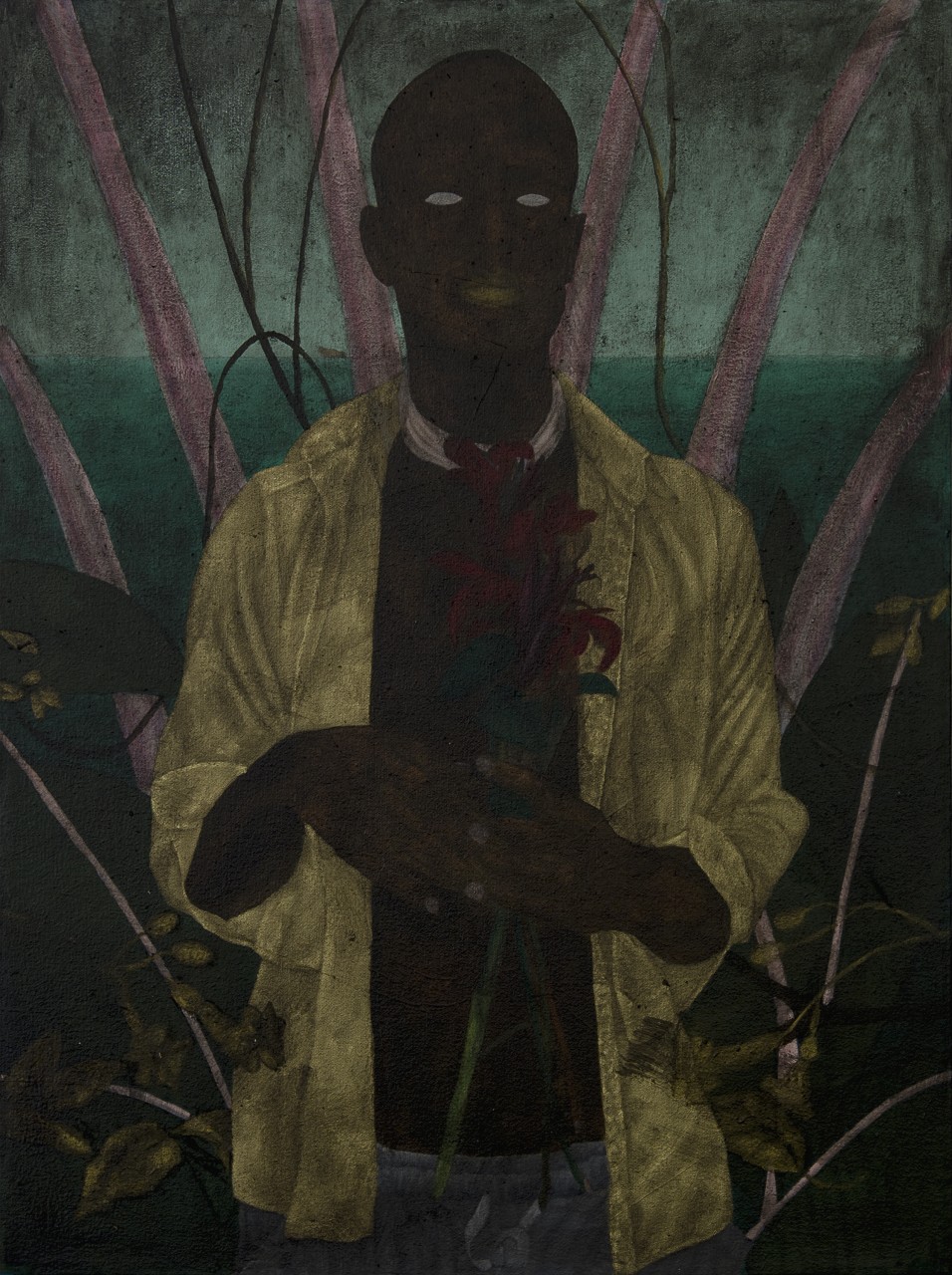

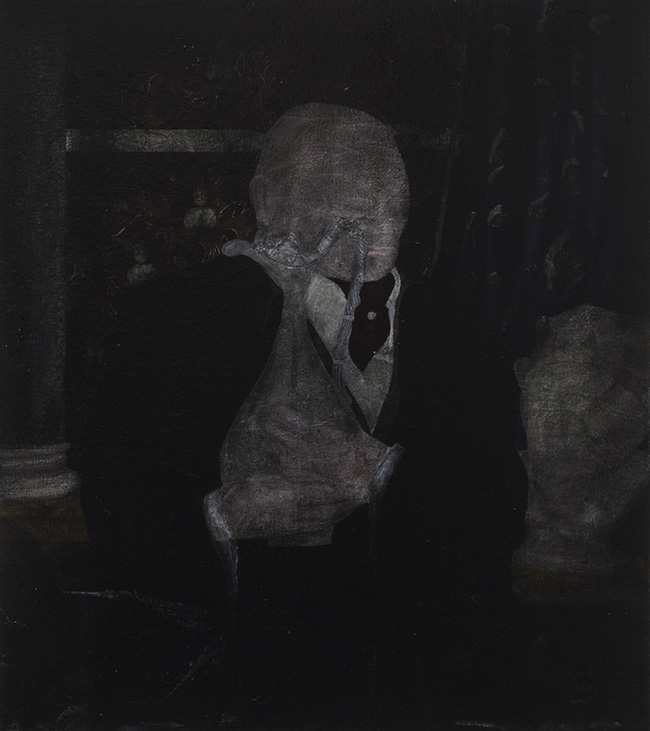

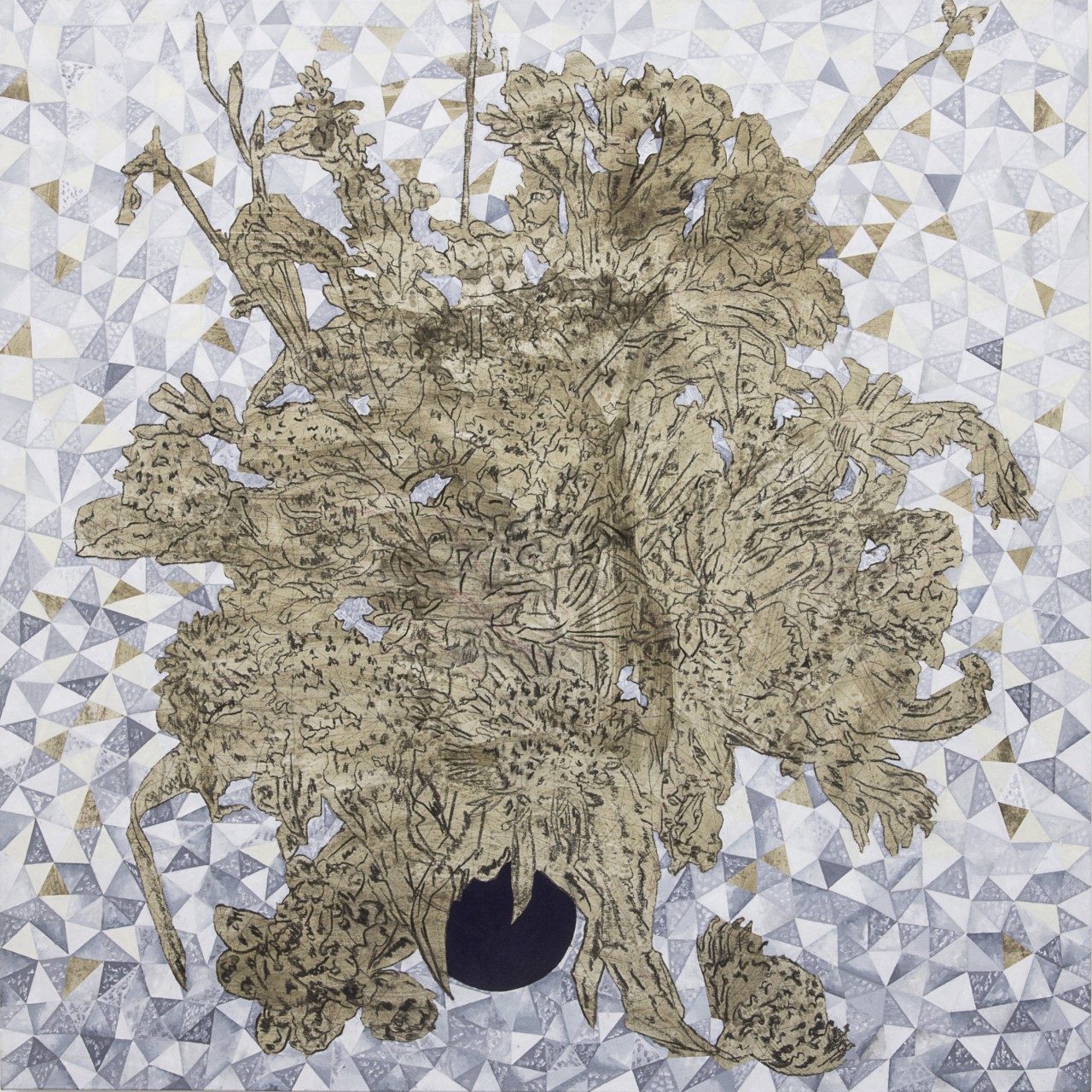

The oil paintings of self-taught artist Cinga Samson (b. 1986, Cape Town) address themes of youth, blackness, masculinity and spirituality against the backdrop of post-colonial South Africa. Figurative self-portraits, the works depict the artist posed in front of landscapes that are surreal composites of his own fantasies and the topography of South Africa. The formal composition of the paintings lend them a traditional, almost anachronistic feeling that is interrupted by the artist’s contemporary clothes, intricately patterned fabrics often bearing the insignia of fake fashion brands commonly found at local street markets. The artist’s focus on beauty is also manifested in the plants, flowers and accessories that his subjects hold or are surrounded by. Samson’s works speak to his pride as a young African man, while at the same time a looming darkness permeates the paintings, suggestive of something more ominous.

To date, Samson has held three solo exhibitions at blank projects: Safari Fantasy (2017), Ubugqoboka Magqoboka(2016) and Thirty Pieces of Silver (2015). He has participated in several group shows, including Mapping Black Identities(Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, 2019); Hacer Noche (Centro Cultural Santo Domingo, Oaxaca de Juarez, 2018); open agenda (blank projects, Cape Town, 2018); A Painting Today (Stevenson, Cape Town, 2017); In the night I remember (Stevenson, Johannesburg, 2013); Our Fathers (AVA Gallery, Cape Town, 2012) and Strata at Greatmore Studios in Cape Town (2011), where he completed a residency. In 2017, Samson won the prestigious Tollman Award, and in 2018 he exhibited with Nicholas Hlobo at the Maitland Institute, in a two-person show titled Umthamo.

“Cinga Samson’s self-portraits present a complex image of black male sensuality and youthful pride. While the figure’s clothing and posture celebrate an aspirational vision of material wealth and luxury often surrounded by rich foliage and bathed in lush patterning, the hollow eyes and dark overall palette hint at a more brooding, introspective gaze that rejects superficiality. For me, this tension between the artist’s inner and outer worlds, and the constructedness of both, is at the core of Samson’s work.”

– Gabriel Ritter, Curator and Head of Contemporary Art, Minneapolis Institute of Art

—

curriculum vitae

1986 Born in Cape Town, South Africa

Lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa

education

2009 Commercial Photography, Stellenbosch Academy

2008 Course in Graphic Design at Learn to Earn in partnership with Stellenbosch University

solo and two-person exhibitions

2019 NaluLwandle, NaliKhaya, blank projects, Cape Town (upcoming)

2018 Umthamo, Maitland Institute, Cape Town (with Nicholas Hlobo)

2017 Safari Fantasy, blank projects, Cape Town

2016 Ubugqoboka Magqoboka, blank projects, Cape Town

2015 Thirty Pieces of Silver, blank projects, Cape Town

2011 Rusting Iron, AVA Gallery, Cape Town

selected group exhibitions

2019 Kubatana, Curated by Kristin Hjellegjerde, Vestfossen Kunstlaboratorium, Øvre Eiker

2019 Mapping Black Identities, Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis

2018 open agenda, blank projects, Cape Town

2018 Hacer Noche, Centro Cultural Santo Domingo, Oaxaca de Juarez

2018 blank, Galerie Guido W. Baudach, Berlin

2017 17, blank projects, Cape Town

2017 A Painting Today, Stevenson, Cape Town

2016 Figure, blank projects, Cape Town

2015 Furniture, blank projects, Cape Town

2013 In the night I remember, Stevenson, Cape Town

2012 Our Fathers, AVA Gallery, Cape Town

2011 STRATA, Greatmore Studios, Cape Town

residencies + workshops

2015 Popty Bach, Llanfihangel-ar-Arth, Wales

2006 Isibane Creative Arts, Khayelitsha, Cape Town

awards

2017 Tollman Award

publications, essays + reviews

2019 Cinga Samson: Capturing the Beauty and Spiritual Side, of Young African Men, by Katy Donoghue, Whitewall Magazine

2019 INSIDE OUT the inner worlds of oil painter Cinga samson demand the viewer looks beyond the surface of his works and into the self-taught artist’s intensely personal universe, by Binwe Adebayo, House & Leisure

2018 Inchule: a portrait of Cinga Samson, Established Africa

2018 Umthamo: Nicholas Hlobo and Cinga Samson, by Cheri Morris, Visi Magazine

2018 Nicholas Hlobo and Cinga Samson at Maitland Institute, by Sean O’Toole, Artforum International

2017 Cinga Samson: Safari Fantasy, Contemporary And

2017 Of Silver and Savages: Cinga Samson and Andrew Gilbert at blank projects, by Annemi Conradie and Natasha Norman, Art Throb

2017 Tollman Award for the Visual Arts awarded to Cinga Samson, 13th Annual Tollman Award

2017 Cinga Samson paints ‘a young man that is desirable in his own sense’, by Louis McCann, Between 10 and 5

News Here

Press

Blablablablablablbalbalabla

Press

Blablablablablablbalbalabla

NaluLwandle, NaliKhaya by Cinga Samson

with acknowledgement to Sikhona Thutha

In the beginning1 there was a river. The river became a road and the road branched out to the whole world. And because the road was once a river it was always hungry. In that land of beginnings spirits mingled with the unborn. We could assume numerous forms. Many of us were birds. We knew no boundaries. There was much feasting, playing, and sorrowing. We feasted much because of the beautiful terrors of eternity. We played much because we were free.

1 The passage is from the opening paragraph of The Famished Road by Ben Okri. The themes which pre-occupy this passage, i.e. temporality, mortality, and existential anxiety, are thematic concerns one finds in Cinga Samson’s body of work, centred on the human figure who is trapped in the swirl of time, in the accumulation of history, and the excesses of progress. This recalls another great African writer, Dambudzo Marechera, whose narrator in The House of Hunger says of his father’s death: “[the] twentieth-century train crunched the old man into a stain.” For the most part post- colonial African literature has always been wary of the manner in which time, disguised as history, acts on the black figure. Often, this act is revealed in the violent event. In Okri, the road, which was once a river, is always hungry. In Marechera, the century crunches the black man into a mere stain. The former writer finds a formal solution to his historical headache in the magical realism of the South American avant-garde in which time is compressed – the past in the present and the present in the past and the future as already history. The latter employs image and metaphor in a frantic stream-of-consciousness prose that assaults the reader just as it reveals the hidden violence of the English language itself. These technical devices help to realise what could be perhaps termed each author’s style. In Samson’s work, we are invited to consider style, what the artist might term beauty, as the pre-eminent concern of the pictorial drama painted on his canvas. The way a Samson painting operates is that it creates clearly delineated surfaces, along horizontal lines and geometric shapes and uses light sparingly and as unnaturally as possible. The unity of the work doesn’t rest on the gradations of light to vivify setting and to create depth. Depth is mere illusion, created by the horizontal planes, which define the foreground, landscape, and sky. However, each of these planes are dislocated and exist individually as separate points of interest on the canvas, which when taken together, formulate the whole and its unity. Each self-contained plane is aware of itself as plane, with its own modalities and peculiarities, thus claiming for the painting itself a modernist slant. For example, light… dim and murky as if it were stars mopped on the bleached fabric of the canvas, draws you into its own uniqueness. In Samson’s work, light doesn’t come from any source of direction but exists entirely as if born out of its own plane and yet its artificiality appears perfect, intentional. The same goes for the landscape, the sky, and the foregrounded figure. Even the shrubbery that is wont to be found in this artist’s work has this absurd quality and yet appears in perfect harmony with itself, firstly, and then with the rest of the elements painted along the surface. This is fresh, innocent, and unique. There are, of course, debts the artist pays to the Old Masters and early Modernists, e.g.: in the Van Eyckian figures of Northern Renaissance portraiture or the Portrait of a Young Girl by Petrus Christus; in the multiple figures on the seashore there’s a slight nod to Cézanne’s The Bathers series or a Poussin drained of dramatic action (rendered not to depict physical vitality but rather to accentuate the quiet interior life of the subject and the painting itself); and in the absence of eyes one recalls Modigliani’s Woman with Blue Eyes. So why is it that with all these debts, one is able to look at Samson’s work and be struck by its originality and singularity of vision? The answer perhaps lies in the conditions set by postcoloniality and the reactions of African writers and painters to it. Here, we’re reminded of Marechera’s unease with English – the very medium of his art: “[You] have to have harrowing fights and hair-raising panga duels with the language before you can make it do all that you want it to do…[t]his may mean discarding grammar, throwing syntax out, subverting images from within.” These subversions are all too clearly articulated in the body of work that Samson has built over this short period as a practicing artist. They are there in the structural discords, in the absurd use of light, in the individuated planes of his dimly pigmented paintings. Part of this subversion has to do with the representation of the black figure, of course. Speaking of Friday, the only black character in JM Coetzee’s Foe, the narrator (an English woman) laments: “I say [Friday] is a cannibal and he becomes a cannibal. I say he is a laundryman and he becomes a laundryman. What is the truth of Friday? No matter what he is to himself… what he is to the world is what I make of him.” Samson is keenly aware of the historical (and present) pathologies heaped upon young black men. He confronts this significance with a style that subverts the pathological with the self-reflexively beautiful… the languid form of his figure, the small pursed mouth daubed with gold paint, the stare which isn’t a stare but a seemingly piqued interest with something other than the external, the white and black of the eyes having disappeared internally, fascinated by a vast interior life of which the viewer is only allowed a glimpse of shape, form, and colour (or lack thereof). Samson’s style seems to emerge from this play: the formal discords, the painterly conversation with art history, the subversion of the black image to lend it irony and nuance. Lastly, mortality. If in the vanitas tradition the transience of life is depicted in the morbidity of the skull and the funereal opulence, in Samson’s work ephemeral materialist objects point toward well-being; an exuberance that is perhaps located within the ambiguities of black post-colonial subjectivity. The very capitalist expansion (disguised in the colonial project) holds within itself meaningful (materialist) liberatory means for the black subject, since his alienation – his marginalisation – is first and foremost a material alienation. Thus, Samson permits his figure life and livity (from the Rastafarian concept of righteous everliving living), against the vanitas’ morbid anxieties about death. NaluLwandle, NaliKhaya (Here’s the sea, Here’s home), finds Samson working closely with his younger brother, Sikhona Thutha, to elaborate on his style and vision and explore new areas and concerns. What the viewer will find novel in this show is the Cézannean congregation of figures by the sea and a harder, more graphic line within the soft silhouette that Samson has developed over the years. The illusive eerie landscapes give way to a more socially realistic setting that is bound to invite further materialist readings. But look closely at the figures at sea, at their eyeless stares, one thrown casually over the shoulder, and you’ll find the artist’s sense of irony still intact, expressed in an almost Velázquezian manner, which makes of the viewer the viewed and the viewed the viewer, thereby closing the distance between the two. It is these sleights of hand and Samson’s style and humour that never fail to make his paintings a delight to look at.

Text by Lwandile Fikeni.

Born in 1986, Cinga Samson lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa. NaluLwandle, NaliKhaya. is the artist’s fourth exhibition with the gallery.

with acknowledgement to Sikhona Thutha

In the beginning1 there was a river. The river became a road and the road branched out to the whole world. And because the road was once a river it was always hungry. In that land of beginnings spirits mingled with the unborn. We could assume numerous forms. Many of us were birds. We knew no boundaries. There was much feasting, playing, and sorrowing. We feasted much because of the beautiful terrors of eternity. We played much because we were free.

1 The passage is from the opening paragraph of The Famished Road by Ben Okri. The themes which pre-occupy this passage, i.e. temporality, mortality, and existential anxiety, are thematic concerns one finds in Cinga Samson’s body of work, centred on the human figure who is trapped in the swirl of time, in the accumulation of history, and the excesses of progress. This recalls another great African writer, Dambudzo Marechera, whose narrator in The House of Hunger says of his father’s death: “[the] twentieth-century train crunched the old man into a stain.” For the most part post- colonial African literature has always been wary of the manner in which time, disguised as history, acts on the black figure. Often, this act is revealed in the violent event. In Okri, the road, which was once a river, is always hungry. In Marechera, the century crunches the black man into a mere stain. The former writer finds a formal solution to his historical headache in the magical realism of the South American avant-garde in which time is compressed – the past in the present and the present in the past and the future as already history. The latter employs image and metaphor in a frantic stream-of-consciousness prose that assaults the reader just as it reveals the hidden violence of the English language itself. These technical devices help to realise what could be perhaps termed each author’s style. In Samson’s work, we are invited to consider style, what the artist might term beauty, as the pre-eminent concern of the pictorial drama painted on his canvas. The way a Samson painting operates is that it creates clearly delineated surfaces, along horizontal lines and geometric shapes and uses light sparingly and as unnaturally as possible. The unity of the work doesn’t rest on the gradations of light to vivify setting and to create depth. Depth is mere illusion, created by the horizontal planes, which define the foreground, landscape, and sky. However, each of these planes are dislocated and exist individually as separate points of interest on the canvas, which when taken together, formulate the whole and its unity. Each self-contained plane is aware of itself as plane, with its own modalities and peculiarities, thus claiming for the painting itself a modernist slant. For example, light… dim and murky as if it were stars mopped on the bleached fabric of the canvas, draws you into its own uniqueness. In Samson’s work, light doesn’t come from any source of direction but exists entirely as if born out of its own plane and yet its artificiality appears perfect, intentional. The same goes for the landscape, the sky, and the foregrounded figure. Even the shrubbery that is wont to be found in this artist’s work has this absurd quality and yet appears in perfect harmony with itself, firstly, and then with the rest of the elements painted along the surface. This is fresh, innocent, and unique. There are, of course, debts the artist pays to the Old Masters and early Modernists, e.g.: in the Van Eyckian figures of Northern Renaissance portraiture or the Portrait of a Young Girl by Petrus Christus; in the multiple figures on the seashore there’s a slight nod to Cézanne’s The Bathers series or a Poussin drained of dramatic action (rendered not to depict physical vitality but rather to accentuate the quiet interior life of the subject and the painting itself); and in the absence of eyes one recalls Modigliani’s Woman with Blue Eyes. So why is it that with all these debts, one is able to look at Samson’s work and be struck by its originality and singularity of vision? The answer perhaps lies in the conditions set by postcoloniality and the reactions of African writers and painters to it. Here, we’re reminded of Marechera’s unease with English – the very medium of his art: “[You] have to have harrowing fights and hair-raising panga duels with the language before you can make it do all that you want it to do…[t]his may mean discarding grammar, throwing syntax out, subverting images from within.” These subversions are all too clearly articulated in the body of work that Samson has built over this short period as a practicing artist. They are there in the structural discords, in the absurd use of light, in the individuated planes of his dimly pigmented paintings. Part of this subversion has to do with the representation of the black figure, of course. Speaking of Friday, the only black character in JM Coetzee’s Foe, the narrator (an English woman) laments: “I say [Friday] is a cannibal and he becomes a cannibal. I say he is a laundryman and he becomes a laundryman. What is the truth of Friday? No matter what he is to himself… what he is to the world is what I make of him.” Samson is keenly aware of the historical (and present) pathologies heaped upon young black men. He confronts this significance with a style that subverts the pathological with the self-reflexively beautiful… the languid form of his figure, the small pursed mouth daubed with gold paint, the stare which isn’t a stare but a seemingly piqued interest with something other than the external, the white and black of the eyes having disappeared internally, fascinated by a vast interior life of which the viewer is only allowed a glimpse of shape, form, and colour (or lack thereof). Samson’s style seems to emerge from this play: the formal discords, the painterly conversation with art history, the subversion of the black image to lend it irony and nuance. Lastly, mortality. If in the vanitas tradition the transience of life is depicted in the morbidity of the skull and the funereal opulence, in Samson’s work ephemeral materialist objects point toward well-being; an exuberance that is perhaps located within the ambiguities of black post-colonial subjectivity. The very capitalist expansion (disguised in the colonial project) holds within itself meaningful (materialist) liberatory means for the black subject, since his alienation – his marginalisation – is first and foremost a material alienation. Thus, Samson permits his figure life and livity (from the Rastafarian concept of righteous everliving living), against the vanitas’ morbid anxieties about death. NaluLwandle, NaliKhaya (Here’s the sea, Here’s home), finds Samson working closely with his younger brother, Sikhona Thutha, to elaborate on his style and vision and explore new areas and concerns. What the viewer will find novel in this show is the Cézannean congregation of figures by the sea and a harder, more graphic line within the soft silhouette that Samson has developed over the years. The illusive eerie landscapes give way to a more socially realistic setting that is bound to invite further materialist readings. But look closely at the figures at sea, at their eyeless stares, one thrown casually over the shoulder, and you’ll find the artist’s sense of irony still intact, expressed in an almost Velázquezian manner, which makes of the viewer the viewed and the viewed the viewer, thereby closing the distance between the two. It is these sleights of hand and Samson’s style and humour that never fail to make his paintings a delight to look at.

Text by Lwandile Fikeni.

Born in 1986, Cinga Samson lives and works in Cape Town, South Africa. NaluLwandle, NaliKhaya. is the artist’s fourth exhibition with the gallery.