blank is pleased to present eBhish', a solo exhibition by Luvuyo Equiano Nyawose (b.1994, eThekwini, South Africa).

[Text by the artist]

I was born eThekwini (formerly Durban)1. Growing up ebhish’ laseThekwini2, summers were often the highlight of the year. My family and I would often drive to the beach in a car packed to the brim with camp chairs, cooler boxes and treats. As kids, we would sing gleefully, ‘eBhish’ Durban, ebhish’, bhish’, bhish’, Durban!’ This excitement reverberated with crowds of other kids who would splash about the public pools. I have fond memories of a mixture of sea water and chlorine. I’d often swim for hours until uMa noma uGogo would drag me out of the pool.

Ibhish’ laseThekwini holds a lot of personal, as well as political, significance for me. The history of black people’s relationship with the space has largely been marked by discrimination and segregation. Our absence in visual archives reflects this, as they are largely populated by historical photographs of white beachgoers.

Saidiya Hartman3 argues that the past is not a time that is over; it is a historical force that produces our now. It is important, therefore, to address the invisibility of black leisure in public spaces4. Through my work, I’m contributing to a contemporary archive of black life ebhish’, one with humanising, tender and intimate moments, aimed at inscribing our place in the seaside eThekwini. To quote Nontobeko Ntombela5, eBhish’ centres “intimacy and embodied knowledge that is enabled through agency, subjectivity and self-articulation… [I]t is not about self-marginalisation but rather an attempt to eradicate totalising interpretations that once serve[d] homogenis[ing]” perceptions of blackness.

The anthropologist Christopher Pinney provides an approach to reading images beyond the fixed connotations of representation:

Pinney’s above concept foregrounds my approach with this body of work: to depict the nuances and finer utterances (seen and unseen) of Black oceanic presence ebhish laseThekwini.

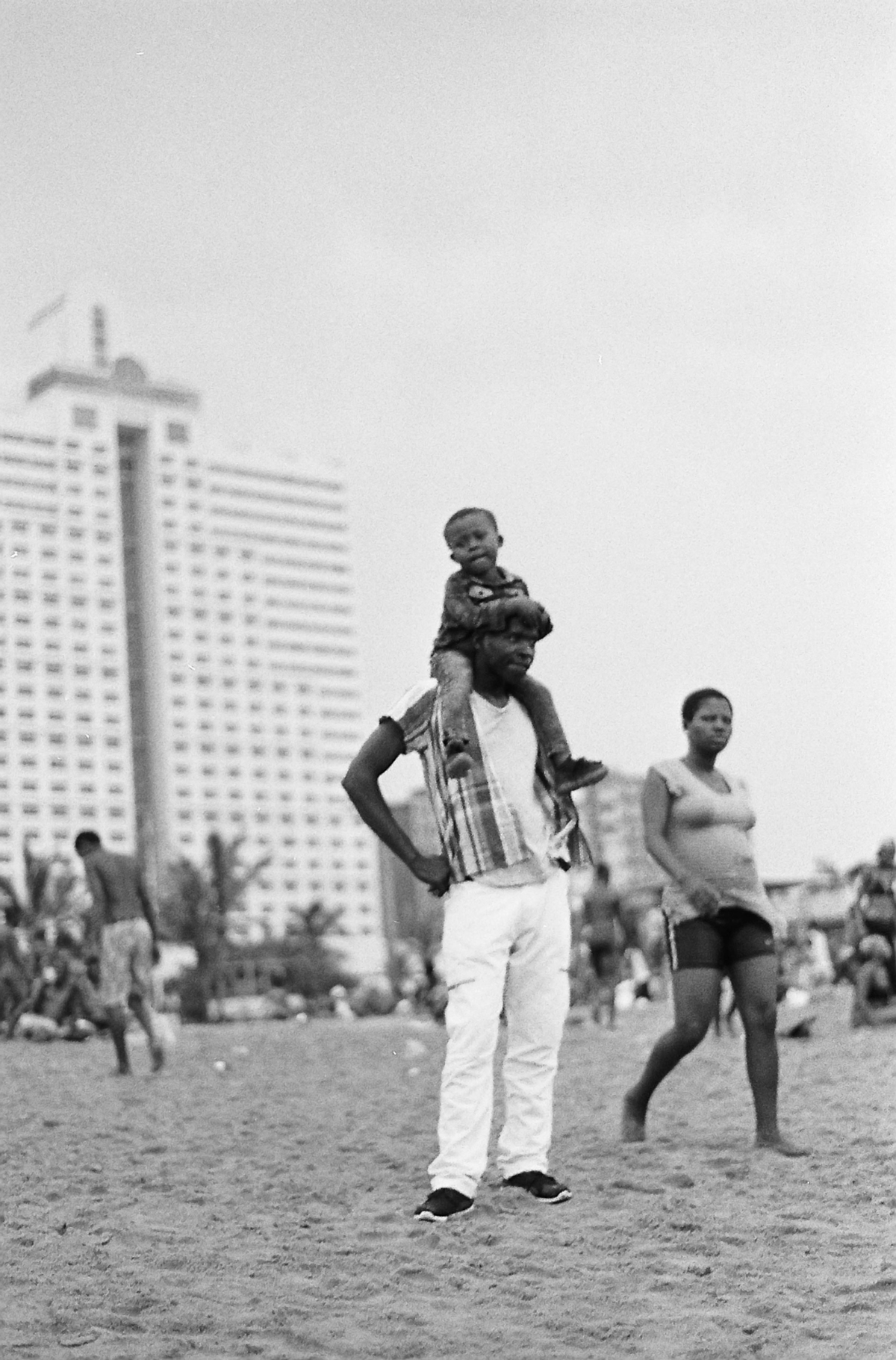

My relationship with photography began at home with personal family albums. On special occasions (umcimbi noma umsebenzi), my family would hire a photographer and videographer to document the moment. As I grew up, I became increasingly curious about image-making and was granted permission to use my parent’s point-and-shoot camera, often used to archive imicimbi nemisebenzi. By the time I entered formal schooling, I had been fully immersed in photography at home. To use bell hooks’ observation, the camera, to me, was something that “gave to black folks, irrespective of class, a means by which we could participate fully in the production of images… [I]t is essential that any theoretical discussion of the relationship of black life to the visual, to art making, make photography central”7. A photograph of me, taken by my father, wearing bright orange swim shorts ebhish’ in 1998 was the genesis of this photographic research. From an early age, I have been documenting (and have been documented in) intimate histories and articulations of community from our perspectives.

![]()

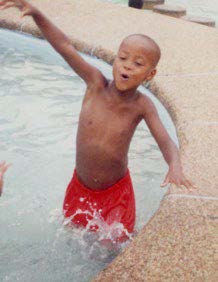

![Emcimbini wezibizo, Kwa-Mashu 2001]()

eBhish’ laseThekwini, 1998 (left);

Emcimbini wezibizo, Kwa-Mashu, 2001 (right)

Photography is more than a form of visual representation. It is a tool for refusing negative portrayals of black people, particularly by white-dominated institutions. My practice is foregrounded in the willingness to be vulnerable8 in the face of the history of photography and to create multivocal imagery which permeates fixed notions of time. The images in eBhish’, taken on old 120mm and 35mm film cameras, are captured while swimming. Although composition is important, the act of swimming whilst documenting is key. The photographic process becomes fluid. The output is, at times, well-composed and focused; at others, there is a soft focus with a skewered horizon line, discarding the formal rules of photographing and composition.

eBhish’ is interested in the finer happenings. It is a self-reflexive endeavour; an archive in the making, unfettered by the tropes of representational image making. It critiques the colonial impulse to name and, therefore, to objectify. Instead, it represents black seaside leisure by being held by it, being in it. This relates specifically to the gathering of black people ebhish’ laseThekwini as an articulation of an unnamed and unnameable space, a metaphysical realm which goes beyond what meets the eye and flesh, yet is crucial for our spiritual survival. Keguro Macharia writes, “The name cannot be thought, now, without the problem of the post-taxonomic imagination we have inherited and that we inhabit. This is a problem of how we got stuck in time, stuck by time, stuck as the timeless, but also as the belated”9.

Through my multimedia work, eBhish’, I take an in-depth look at the history of ibhish’ laseThekwini. Presented through a historiography, I unpack systemic enactments, allowing us to understand the past that has not passed, but reappears always and ruptures the present10. Drawing from the history of ibhish’ laseThekwini, I critique the photographic archive and its representational politics. By doing so, I hope to foreground the multiplicity and fluidity of black oceanic presence and black subjectivity, as well as the interrelated meanings of water and the sea as spiritual.

Notes

1 Durban was named after a governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Benjamin D’Urban, on 23 June 1835. Prior to that, it was known as Port Natal. iTheku (meaning a port or harbour) is the proper noun. eThekwini is a prepositional version which means in/at the theku.

2 Throughout the text, I will use ibhish’ laseThekwini, ebhish lase’Thekwini or ebhish’ when discussing the Durban beach. This is in line with the renaming of the city from Durban (a colonial name) to eThekwini. This does not abide by the English convention and naming of the space, but it is culturally and colloquially acceptable. In isiZulu, ebhish’ means at the beach and ibhish’ means the beach, depending on the context. There are moments in which English requires the inclusion of ‘the’ or ‘at’. In this case, those words are excluded.

3 Hartman, S. (2019). Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals. W. W. Norton & Company.

4 The question of black leisure represents a tension between racial capitalism and leisure. Leisure is seen as opposed to capitalism: “free time” versus “work time”. It is the fact of not owning one’s own labour (thus time) that's the key issue. In the contemporary, we all exist within the same structure, but the notion of “free time” is designed to make it more possible to accept a capitalist realist conception of the world. Arguably, if we take this into account then the notion of leisure is fraught with the idea that enjoyment only exists within a constructed framework of class division. To a degree, it accepts a colonial parameterisation around where social enjoyment lives and does not live.

5 Ntombela, N. (2019). The Yoni Book, The Two Talking Yonis, Reshma Chhiba and Nontobeko Ntombela, eds., p. 96.

6 Pinney, C. (2003). Photography’s Other Histories. Christopher Pinney, Nicolas Peterson eds. Duke University Press Books, pp. 4-5.

7 hooks, b. (1994). “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” in Deborah Willis-Thomas, ed. Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography. W.W. Norton & Co., p. 57.

8 Whether the photograph captured is problematic or not, vulnerability is always inevitable around the camera.

9 Macharia, K. (2016). “Reflection of Trans* & Taxonomy (With Musangi).” Critical Arts Projects & UNISA Press, pp. 31-42.

10 Sharpe. C. (2016). In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press, p. 41.

Luvuyo Equiano Nyawose is an artist, curator, filmmaker, researcher, and sessional lecturer. He received his MFA from the Michaelis School of Fine Arts at University of Cape Town in 2021. He also holds a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in Curatorship from the Centre for Curating the Archive at the University of Cape Town (2018), and a Bachelor of Arts in Motion Picture Medium from AFDA’s School for the Creative Economy in Cape Town.

[Text by the artist]

I was born eThekwini (formerly Durban)1. Growing up ebhish’ laseThekwini2, summers were often the highlight of the year. My family and I would often drive to the beach in a car packed to the brim with camp chairs, cooler boxes and treats. As kids, we would sing gleefully, ‘eBhish’ Durban, ebhish’, bhish’, bhish’, Durban!’ This excitement reverberated with crowds of other kids who would splash about the public pools. I have fond memories of a mixture of sea water and chlorine. I’d often swim for hours until uMa noma uGogo would drag me out of the pool.

Ibhish’ laseThekwini holds a lot of personal, as well as political, significance for me. The history of black people’s relationship with the space has largely been marked by discrimination and segregation. Our absence in visual archives reflects this, as they are largely populated by historical photographs of white beachgoers.

Saidiya Hartman3 argues that the past is not a time that is over; it is a historical force that produces our now. It is important, therefore, to address the invisibility of black leisure in public spaces4. Through my work, I’m contributing to a contemporary archive of black life ebhish’, one with humanising, tender and intimate moments, aimed at inscribing our place in the seaside eThekwini. To quote Nontobeko Ntombela5, eBhish’ centres “intimacy and embodied knowledge that is enabled through agency, subjectivity and self-articulation… [I]t is not about self-marginalisation but rather an attempt to eradicate totalising interpretations that once serve[d] homogenis[ing]” perceptions of blackness.

The anthropologist Christopher Pinney provides an approach to reading images beyond the fixed connotations of representation:

Pinney terms “Looking Past'' to describe a reading practice [in] which subaltern subjects challenge dominant visual representation and photography in particular. Pinney writes, “Looking Past” suggests a complexity of perspectival positions or a multiplicity of layers that endow photographs with an enormously greater complexity than that which they are usually credited. The photograph ceases to be a univocal, flat, and incontestable indexical trace of what was, and becomes instead a complexly textured artifact concealing many different standpoints, both spatial and temporal in respect to it.6

Pinney’s above concept foregrounds my approach with this body of work: to depict the nuances and finer utterances (seen and unseen) of Black oceanic presence ebhish laseThekwini.

My relationship with photography began at home with personal family albums. On special occasions (umcimbi noma umsebenzi), my family would hire a photographer and videographer to document the moment. As I grew up, I became increasingly curious about image-making and was granted permission to use my parent’s point-and-shoot camera, often used to archive imicimbi nemisebenzi. By the time I entered formal schooling, I had been fully immersed in photography at home. To use bell hooks’ observation, the camera, to me, was something that “gave to black folks, irrespective of class, a means by which we could participate fully in the production of images… [I]t is essential that any theoretical discussion of the relationship of black life to the visual, to art making, make photography central”7. A photograph of me, taken by my father, wearing bright orange swim shorts ebhish’ in 1998 was the genesis of this photographic research. From an early age, I have been documenting (and have been documented in) intimate histories and articulations of community from our perspectives.

eBhish’ laseThekwini, 1998 (left);

Emcimbini wezibizo, Kwa-Mashu, 2001 (right)

Photography is more than a form of visual representation. It is a tool for refusing negative portrayals of black people, particularly by white-dominated institutions. My practice is foregrounded in the willingness to be vulnerable8 in the face of the history of photography and to create multivocal imagery which permeates fixed notions of time. The images in eBhish’, taken on old 120mm and 35mm film cameras, are captured while swimming. Although composition is important, the act of swimming whilst documenting is key. The photographic process becomes fluid. The output is, at times, well-composed and focused; at others, there is a soft focus with a skewered horizon line, discarding the formal rules of photographing and composition.

eBhish’ is interested in the finer happenings. It is a self-reflexive endeavour; an archive in the making, unfettered by the tropes of representational image making. It critiques the colonial impulse to name and, therefore, to objectify. Instead, it represents black seaside leisure by being held by it, being in it. This relates specifically to the gathering of black people ebhish’ laseThekwini as an articulation of an unnamed and unnameable space, a metaphysical realm which goes beyond what meets the eye and flesh, yet is crucial for our spiritual survival. Keguro Macharia writes, “The name cannot be thought, now, without the problem of the post-taxonomic imagination we have inherited and that we inhabit. This is a problem of how we got stuck in time, stuck by time, stuck as the timeless, but also as the belated”9.

Through my multimedia work, eBhish’, I take an in-depth look at the history of ibhish’ laseThekwini. Presented through a historiography, I unpack systemic enactments, allowing us to understand the past that has not passed, but reappears always and ruptures the present10. Drawing from the history of ibhish’ laseThekwini, I critique the photographic archive and its representational politics. By doing so, I hope to foreground the multiplicity and fluidity of black oceanic presence and black subjectivity, as well as the interrelated meanings of water and the sea as spiritual.

Notes

1 Durban was named after a governor of the Cape Colony, Sir Benjamin D’Urban, on 23 June 1835. Prior to that, it was known as Port Natal. iTheku (meaning a port or harbour) is the proper noun. eThekwini is a prepositional version which means in/at the theku.

2 Throughout the text, I will use ibhish’ laseThekwini, ebhish lase’Thekwini or ebhish’ when discussing the Durban beach. This is in line with the renaming of the city from Durban (a colonial name) to eThekwini. This does not abide by the English convention and naming of the space, but it is culturally and colloquially acceptable. In isiZulu, ebhish’ means at the beach and ibhish’ means the beach, depending on the context. There are moments in which English requires the inclusion of ‘the’ or ‘at’. In this case, those words are excluded.

3 Hartman, S. (2019). Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments: Intimate Histories of Riotous Black Girls, Troublesome Women, and Queer Radicals. W. W. Norton & Company.

4 The question of black leisure represents a tension between racial capitalism and leisure. Leisure is seen as opposed to capitalism: “free time” versus “work time”. It is the fact of not owning one’s own labour (thus time) that's the key issue. In the contemporary, we all exist within the same structure, but the notion of “free time” is designed to make it more possible to accept a capitalist realist conception of the world. Arguably, if we take this into account then the notion of leisure is fraught with the idea that enjoyment only exists within a constructed framework of class division. To a degree, it accepts a colonial parameterisation around where social enjoyment lives and does not live.

5 Ntombela, N. (2019). The Yoni Book, The Two Talking Yonis, Reshma Chhiba and Nontobeko Ntombela, eds., p. 96.

6 Pinney, C. (2003). Photography’s Other Histories. Christopher Pinney, Nicolas Peterson eds. Duke University Press Books, pp. 4-5.

7 hooks, b. (1994). “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life,” in Deborah Willis-Thomas, ed. Picturing Us: African American Identity in Photography. W.W. Norton & Co., p. 57.

8 Whether the photograph captured is problematic or not, vulnerability is always inevitable around the camera.

9 Macharia, K. (2016). “Reflection of Trans* & Taxonomy (With Musangi).” Critical Arts Projects & UNISA Press, pp. 31-42.

10 Sharpe. C. (2016). In the Wake: On Blackness and Being. Duke University Press, p. 41.

Luvuyo Equiano Nyawose is an artist, curator, filmmaker, researcher, and sessional lecturer. He received his MFA from the Michaelis School of Fine Arts at University of Cape Town in 2021. He also holds a Bachelor of Arts (Honours) in Curatorship from the Centre for Curating the Archive at the University of Cape Town (2018), and a Bachelor of Arts in Motion Picture Medium from AFDA’s School for the Creative Economy in Cape Town.