Lerato Shadi, I know what a closed fist means (2020) | Site-specific installation of photographic prints on board, dimensions variable | Installation view at Kunstverein in Hamburg

I know what a closed fist means continues Shadi’s interrogation of supposedly universal assumptions, emphasized through subjective readings of her art. Four oversized photographs depict raised fists with the position of the thumb in each image having a variety of associated meanings that differ depending on the viewer’s own cultural background. The work’s title contradicts the endless possibility for interpretation of the individually raised fists - Shadi makes it clear that knowledge and experience are always connected to one’s own perspective and cannot be easily generalized.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Lerato Shadi, Ngono Le Nna (2020) | Site-specific installation, dimensions variable | Installation view, KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art, Berlin

Ngono Le Nna is closely tied with the notion of “we”, where Shadi is thinking of herself in relation to her family history. Distance is articulated through the space between the wall-based neon X and Shadi’s signature. The X represents the artist’s great grandmother, Ngono, or rather it (re)inscribes her, bringing her into relation with the artist. It is a way of describing what it means to be close to or far away from each other. […] Through this work, Shadi presents us with a question of her own; what is the space between me and the furthest traceable matriarch in my lineage? Perhaps the space between is lost knowledge – the differences between western epistemology and historical and customary epistemology.

I know what a closed fist means continues Shadi’s interrogation of supposedly universal assumptions, emphasized through subjective readings of her art. Four oversized photographs depict raised fists with the position of the thumb in each image having a variety of associated meanings that differ depending on the viewer’s own cultural background. The work’s title contradicts the endless possibility for interpretation of the individually raised fists - Shadi makes it clear that knowledge and experience are always connected to one’s own perspective and cannot be easily generalized.

Lerato Shadi, Ngono Le Nna (2020) | Site-specific installation, dimensions variable | Installation view, KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art, Berlin

Ngono Le Nna is closely tied with the notion of “we”, where Shadi is thinking of herself in relation to her family history. Distance is articulated through the space between the wall-based neon X and Shadi’s signature. The X represents the artist’s great grandmother, Ngono, or rather it (re)inscribes her, bringing her into relation with the artist. It is a way of describing what it means to be close to or far away from each other. […] Through this work, Shadi presents us with a question of her own; what is the space between me and the furthest traceable matriarch in my lineage? Perhaps the space between is lost knowledge – the differences between western epistemology and historical and customary epistemology.

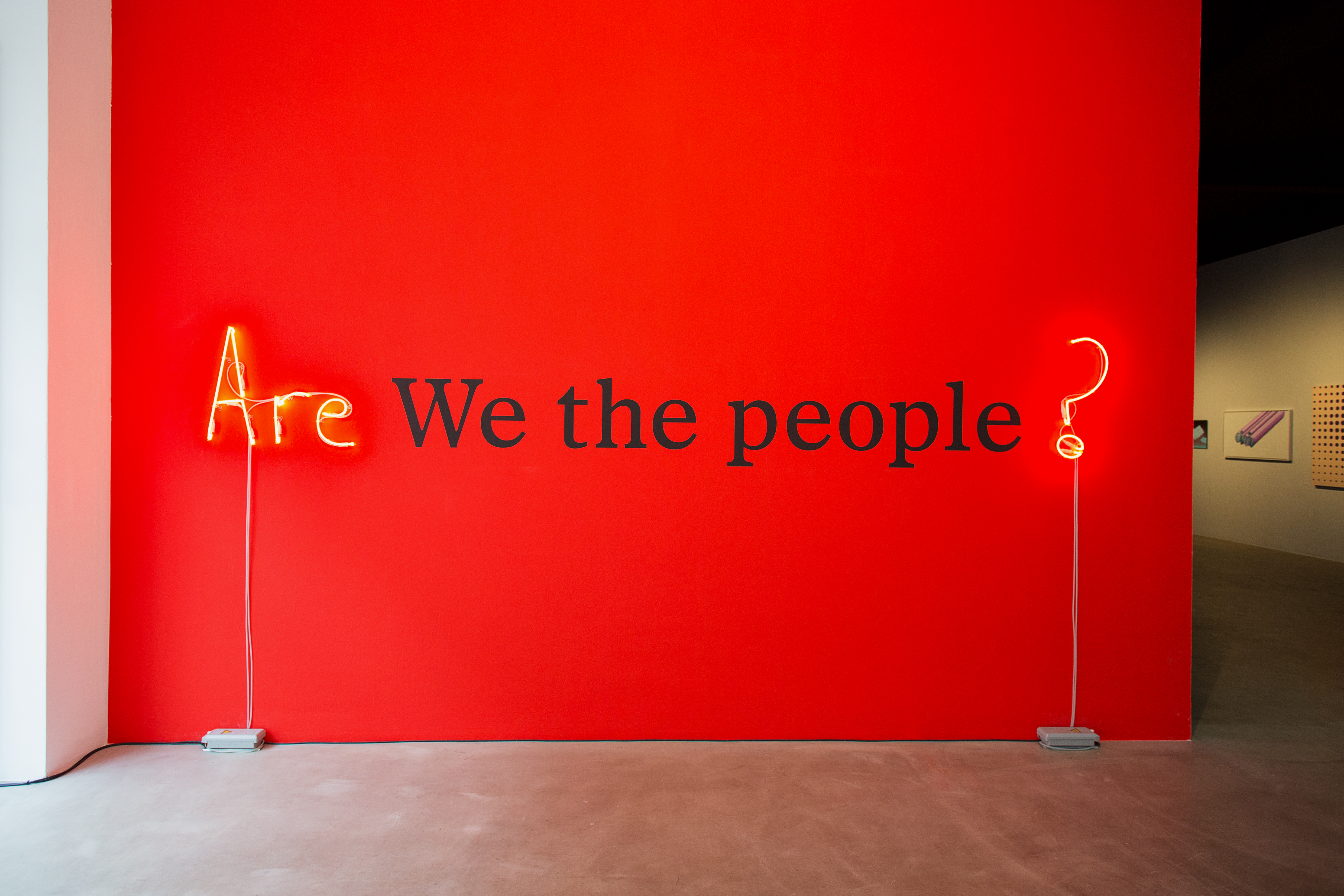

Lerato Shadi, Batho ba me (2020) | Text based neon installation on red wall, approx. 400 x 550 cm | Installation view at Neuer Berliner Kunstverein | link to artist statement

In her installations, performances, and video works, Lerato Shadi points out processes of suppression, exclusion, and erasure. The spaces of remembrance and visibility she creates invite reflection on the position of the artist and on the subjects she deals with, as well as a critical examination of the role of the viewer. Her work engages in questions concerning the possibilities of one’s own actions and the constitution of future communities. Her work Batho ba me, created for the exhibition, quotes the opening phrase “We the people” found in the constitutions of numerous states and expands it to pose the question “Are we the people?” Like all the titles of her works, which are in Shadi’s native language Setswana, Batho ba me (“My people”) points to a lived context that not everyone can access, thus questioning how the notion of a “we” is formed. The “own” people who are addressed in political speeches often indicate a certain group of voters. The structural exclusion that underpins assumed and legal groups like these has to be continuously questioned. — Michaela Richter, Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, 2020

In her installations, performances, and video works, Lerato Shadi points out processes of suppression, exclusion, and erasure. The spaces of remembrance and visibility she creates invite reflection on the position of the artist and on the subjects she deals with, as well as a critical examination of the role of the viewer. Her work engages in questions concerning the possibilities of one’s own actions and the constitution of future communities. Her work Batho ba me, created for the exhibition, quotes the opening phrase “We the people” found in the constitutions of numerous states and expands it to pose the question “Are we the people?” Like all the titles of her works, which are in Shadi’s native language Setswana, Batho ba me (“My people”) points to a lived context that not everyone can access, thus questioning how the notion of a “we” is formed. The “own” people who are addressed in political speeches often indicate a certain group of voters. The structural exclusion that underpins assumed and legal groups like these has to be continuously questioned. — Michaela Richter, Neuer Berliner Kunstverein, 2020

Lerato Shadi, Series #1–4 (2020) | Site-specific installation, dimensions variable | Installation view, KINDL – Centre for Contemporary Art, Berlin

Made from virgin wool on raw linen, Series #1–4 (whose titles are yet to announce themselves) is a return to perfomativity. Mounted on the wall; a set of three rectangles, a single square and a vertical rectangle resembling a doorway, the works have considerable presence. Movement is the first language as the work is informed by small repetitive gestures accumulated over time. The works in Series #1–4 are connected to the process of fasting, which Shadi uses as a method to remind the body to pay attention. In this sense, the body is not merely a porous absorbent but it works to produce its own forms of knowledge.

Lerato Shadi, Mosako Wa Nako (2014 - ongoing) | Performance and installation, installation dimensions variable, duration 10 days | Installation view, Neue Berliner Kunstverein (n.b.k.), Berlin

Shadi speaks of Mosako Wa Nako as a red river. It is the product of 60 hours of labour, which Shadi carries out publicly over the course of 10 days. It is a futuristic work, a call for the brave to carve their own tomorrows while acknowledging the stasis of today. The crocheted object is rendered as a representation of silent narratives and acts as an architectural feature that divides the space. As M. Neelika Jayawardane states: “In highlighting work that is usually associated with feminised—and therefore often inconspicuous and devalued labour, Shadi focuses our attention to the meditative quality of her actions. Bringing the experience of meditation into her labour allows her to be present in her body and in the present moment-to-moment of labour, and for us, as her audience, to be similarly mindful in the space”.

Shadi speaks of Mosako Wa Nako as a red river. It is the product of 60 hours of labour, which Shadi carries out publicly over the course of 10 days. It is a futuristic work, a call for the brave to carve their own tomorrows while acknowledging the stasis of today. The crocheted object is rendered as a representation of silent narratives and acts as an architectural feature that divides the space. As M. Neelika Jayawardane states: “In highlighting work that is usually associated with feminised—and therefore often inconspicuous and devalued labour, Shadi focuses our attention to the meditative quality of her actions. Bringing the experience of meditation into her labour allows her to be present in her body and in the present moment-to-moment of labour, and for us, as her audience, to be similarly mindful in the space”.

Lerato Shadi, Tlhogo (2010) | Durational performance, approx. 2.5 hours | Installation view, Dakar Biennale 2012

For the performance Tlhogo, Shadi crochets a cocoon from hand-spun wool of various origins. The red woollen sheath is created specifically to fit her body, with just enough space left open for her to enter it. The performance takes place on a plinth in the gallery. First the artist struggles into the woollen cover and closes up the entrance by crocheting it from the inside. For the rest of the duration of the performance, the swaddled body lies motionless on the plinth, a 'living object'. At first glance the viewer is unable to tell that the 'object' is alive - only on close inspection does the movement of breathing become noticeable. The artist/performer changes position four times during the course of the evening, to relieve the body and to create a different sculptural image. Finally, Shadi liberates herself from the woollen cover, leaving behind the crocheted 'relic'.

For the performance Tlhogo, Shadi crochets a cocoon from hand-spun wool of various origins. The red woollen sheath is created specifically to fit her body, with just enough space left open for her to enter it. The performance takes place on a plinth in the gallery. First the artist struggles into the woollen cover and closes up the entrance by crocheting it from the inside. For the rest of the duration of the performance, the swaddled body lies motionless on the plinth, a 'living object'. At first glance the viewer is unable to tell that the 'object' is alive - only on close inspection does the movement of breathing become noticeable. The artist/performer changes position four times during the course of the evening, to relieve the body and to create a different sculptural image. Finally, Shadi liberates herself from the woollen cover, leaving behind the crocheted 'relic'.

Lerato Shadi, Seriti Se (2016) | Performance and installation, dimensions variable | Installation view, Goethe Institut, Johannesburg

The performance, drawing and installation Seriti Se looks at the politics of historical erasure, specifically of Black females and their achievements and contributions within various fields. Seriti Se thematises everyday violence enacted within institutional structures and the different strategies employed within those systems. During the performance, names of historical women of colour, who have been excluded and erased from world history, are written on the white walls of the gallery. The audience is then invited to choose a name and paint over the chosen name. In the act of erasing a name, the gallery space is turned back to white. No information is provided on who the women on the wall are; therefore it becomes the duty of the one who is erasing the name to take responsibility for the name by further informing themselves.

The performance, drawing and installation Seriti Se looks at the politics of historical erasure, specifically of Black females and their achievements and contributions within various fields. Seriti Se thematises everyday violence enacted within institutional structures and the different strategies employed within those systems. During the performance, names of historical women of colour, who have been excluded and erased from world history, are written on the white walls of the gallery. The audience is then invited to choose a name and paint over the chosen name. In the act of erasing a name, the gallery space is turned back to white. No information is provided on who the women on the wall are; therefore it becomes the duty of the one who is erasing the name to take responsibility for the name by further informing themselves.

Lerato Shadi, Makhubu (2014) | Performative drawing and installation, dimensions variable | Installation view, Iniva, London

Shadi's drawing performance, Makhubu, is divided into two parts; in the first half of the performance she writes texts in circles directly in the gallery wall, and in the second half she then erases what she has written. This process is repeated three times. This work is based on the understanding that the artist is not in control of the archive of her own history, and attempts to reconcile the difference between what is on record and her actual, lived experience. Shadi wants to bring about an awareness of the biased nature of historical 'fact', and that whoever is in control of the archive of history has the power to affect the perception of it as well as the future. In Makhubu, Shadi writes specifically about the possible future of her own life, and the place that her artistic practice may have in our collective history.

Shadi's drawing performance, Makhubu, is divided into two parts; in the first half of the performance she writes texts in circles directly in the gallery wall, and in the second half she then erases what she has written. This process is repeated three times. This work is based on the understanding that the artist is not in control of the archive of her own history, and attempts to reconcile the difference between what is on record and her actual, lived experience. Shadi wants to bring about an awareness of the biased nature of historical 'fact', and that whoever is in control of the archive of history has the power to affect the perception of it as well as the future. In Makhubu, Shadi writes specifically about the possible future of her own life, and the place that her artistic practice may have in our collective history.

Lerato Shadi, Mabogo Dinku (2019)| Single channel video work with audio 00:06:00

In the video Mabogo Dinku, Shadi’s hand makes enigmatic gestures and she sings a folk verse in Setswana. But she provides no subtitles or guidance on what the words and gestures mean because she is narrating the un-narratable, the history of her people, marginalized during apartheid in South Africa. The history she was taught at school is the history of the colonizer, which she rejects, so what history can she tell? Furthermore, the translation of the language into English or other dominant western languages would pay homage to western languages as the universal one, continuing the boxing in of others’ mother tongues into the languages of the “other.”

Text by Winnie Sze

In the video Mabogo Dinku, Shadi’s hand makes enigmatic gestures and she sings a folk verse in Setswana. But she provides no subtitles or guidance on what the words and gestures mean because she is narrating the un-narratable, the history of her people, marginalized during apartheid in South Africa. The history she was taught at school is the history of the colonizer, which she rejects, so what history can she tell? Furthermore, the translation of the language into English or other dominant western languages would pay homage to western languages as the universal one, continuing the boxing in of others’ mother tongues into the languages of the “other.”

Text by Winnie Sze

Lerato Shadi, Re Maotwana Gonyela (2016 - 2018) | Single channel video, 00:11:15

In Re Maotwana Gonyela, a figure completely draped in red roams a landscape as the personified spirit of resistance. Sometimes they pause in contemplation, sometimes they wander through the tall grass, then stop again to perform mysterious movements. Their intentions and actions remain vague, oscillating between energetic and gentle moments and underlining the ghostly character of the figure. Apart from the figure, nothing indicates human presence, so that the scene has hardly any temporal or spatial coordinates. Thus, the spirit of resistance is detached from past, present and future and inscribed in a landscape in which their presence equally leaves their mark.

In Re Maotwana Gonyela, a figure completely draped in red roams a landscape as the personified spirit of resistance. Sometimes they pause in contemplation, sometimes they wander through the tall grass, then stop again to perform mysterious movements. Their intentions and actions remain vague, oscillating between energetic and gentle moments and underlining the ghostly character of the figure. Apart from the figure, nothing indicates human presence, so that the scene has hardly any temporal or spatial coordinates. Thus, the spirit of resistance is detached from past, present and future and inscribed in a landscape in which their presence equally leaves their mark.

Lerato Shadi, Motlhaba Wa Re Ke Namile (2016) | Single channel video projection, 00:07:30

The video Motlhaba Wa Re Ke Namile was shot on location in Shadi’s home village of Lotlhakane in Mahikeng, Northwest Province, South Africa. The video references the slave mask used on enslaved people; specifically how the mask was used to prevent the slaves from committing suicide through the act of consuming soil. The work looks at how the act of eating soil to commit suicide, has over the years been overlooked as a form of resistance. The video also makes reference to the challenges on land dispossession, belonging and displacement.

The video Motlhaba Wa Re Ke Namile was shot on location in Shadi’s home village of Lotlhakane in Mahikeng, Northwest Province, South Africa. The video references the slave mask used on enslaved people; specifically how the mask was used to prevent the slaves from committing suicide through the act of consuming soil. The work looks at how the act of eating soil to commit suicide, has over the years been overlooked as a form of resistance. The video also makes reference to the challenges on land dispossession, belonging and displacement.

Lerato Shadi, Sugar & Salt (2014) | Single channel video, 00:06:00

The video Sugar & Salt shows a mother and daughter who are licking sugar and salt from each other’s tongues - sugar being licked and consumed off the mother’s tongue and salt off the daughter’s tongue - against the backdrop of intricately ornamental pattern. The scenery acts as a vanishing point for the camera lens, at the same time the pattern creates a border between the two generations. The video looks at inter-generational relationships and narratives while using two substances - one a carbohydrate and the other a mineral - that look the same but are structurally different, thematising the interaction off screen.

The video Sugar & Salt shows a mother and daughter who are licking sugar and salt from each other’s tongues - sugar being licked and consumed off the mother’s tongue and salt off the daughter’s tongue - against the backdrop of intricately ornamental pattern. The scenery acts as a vanishing point for the camera lens, at the same time the pattern creates a border between the two generations. The video looks at inter-generational relationships and narratives while using two substances - one a carbohydrate and the other a mineral - that look the same but are structurally different, thematising the interaction off screen.

Lerato Shadi, Matsogo (2013) | Single channel video, 00:05:00

The video Matsogo shows a pair of hands crumbling a piece of cake and reforming it into the same wedge shape that references the original slice. Through the process of moving from deconstruction to reconstruction, the essence and consumability of the slice of cake is undermined and lost, as it is recreated into an object, that resembles and has the same elements, as the cake, but has lost its function. The soundtrack combines songs from two different popular Setswana folktales. The songs are mixed together, thereby confusing and convoluting the narratives in such a way that there are three to five characters in an ongoing polylogue, which revolves around belief and disbelief, trust and betrayal.

The video Matsogo shows a pair of hands crumbling a piece of cake and reforming it into the same wedge shape that references the original slice. Through the process of moving from deconstruction to reconstruction, the essence and consumability of the slice of cake is undermined and lost, as it is recreated into an object, that resembles and has the same elements, as the cake, but has lost its function. The soundtrack combines songs from two different popular Setswana folktales. The songs are mixed together, thereby confusing and convoluting the narratives in such a way that there are three to five characters in an ongoing polylogue, which revolves around belief and disbelief, trust and betrayal.