blank is pleased to present See you in happiness, a solo exhibition by James Webb.

The exhibition loosely gathers around the themes of memorialisation and remembrance, and those histories of nationalism and violence whose legacies continue to cast their long shadows.

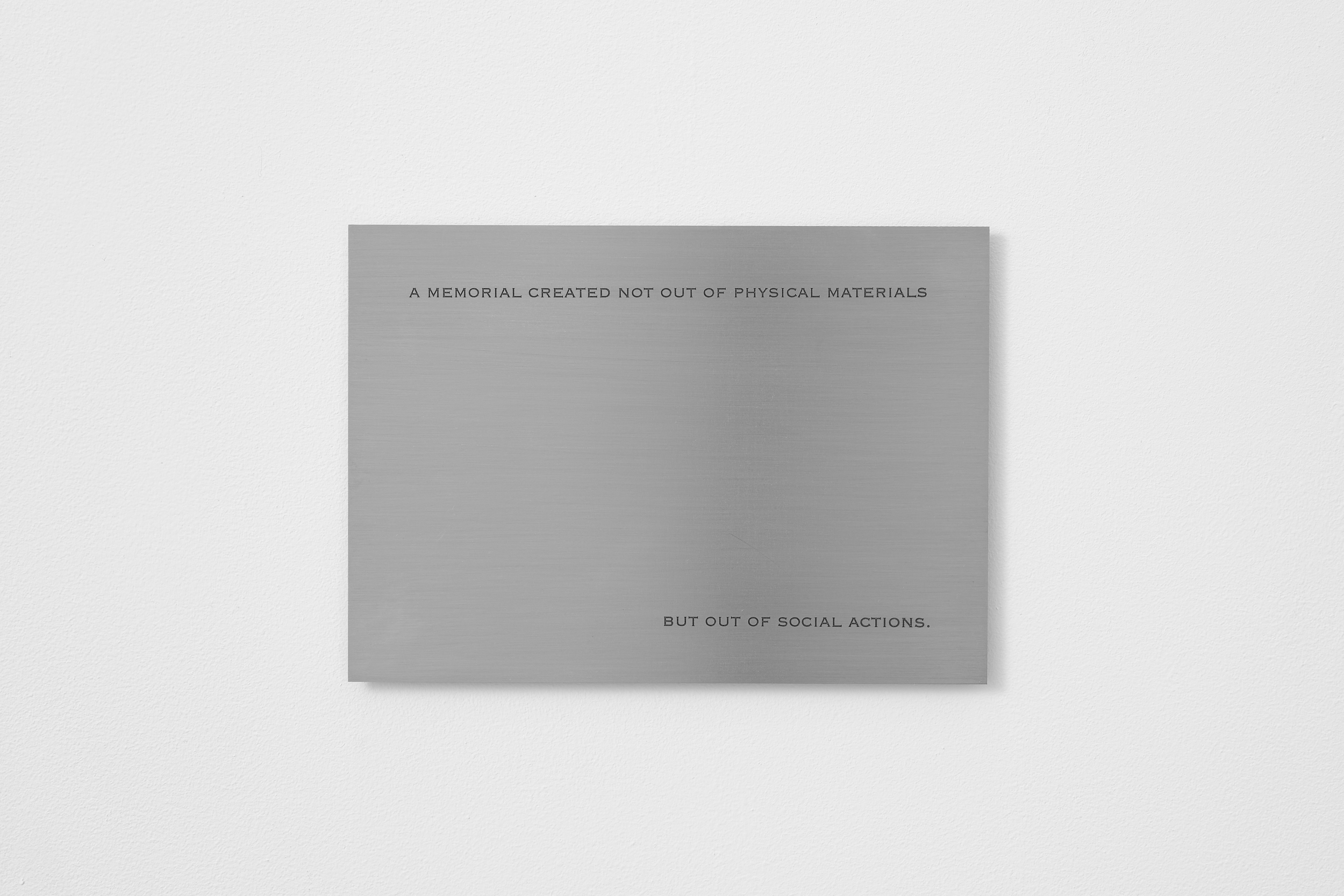

The four new works on show — an installation, a photograph, a sculpture, and a sound piece — represent, in various ways, processes of transformation and transcendence: a WW2 Africa Service Medal forged into a silver nail; the sky over Nagasaki photographed from the Atomic Bomb Hypocentre; a text piece prompting us to conceive of a memorial as a social action; and a re-arrangement of the traditional folksong, ‘The Mermaid’, whose final verse serves both as a warning and a temptation.

Deriving its title from an expression of farewell once common in Arabic, Hebrew, and Turkish, the exhibition draws from the past in an attempt to name our desires for the future; a wish, even, for happiness.

See you in happiness is the artist’s sixth exhibition with the gallery.

-

You and I have never met, and perhaps we never will, but not too long ago, I stood where you are standing now. I imagine that you have your own reasons for being here, your own collection of griefs. Perhaps, like Auden in ‘September 1, 1939’, “you’re uncertain and afraid.” The nail you’re looking at is forged from a Second World War African Service Medal, similar to the one issued to the artist's grandfather. This may mean nothing to you, an arcane piece of military history that doesn’t strike a common chord. World War II, after all, ended eighty years ago, long before your time. Or maybe the war means everything to you because someone in your family was spared from a catastrophe at the eleventh hour. If you happen to be Palestinian, say, or Sudanese, the killing of thousands is not just a thing of the past. (In Chi Shona, the act of visiting the home of the bereaved is known as kubata maoko, which means to hold the hand of the bereaved. Perhaps this is one of the consolations that poetry and art can offer: to hold your hand, even as your world hangs in the balance.) Or perhaps, like me, you find yourself reminded of your own grandfather, who perished in one of the slaughterhouses of the 20th century. Closing my eyes, I can almost see him in the distance of the past, enclosed in a circle of men at daybreak, on the morning of his crucifixion. Perhaps he is blindfolded, perhaps he is not. Please, Brother, I plead with the man in whose hands the gun is placed. Have mercy. There is no such. The man who pulls the trigger has long vanished into the wide stream of history. Who knows what becomes of him, or his accomplices. Perhaps, after the war ends, the gunman will find work with the postal service or as a bank clerk. He will say nothing about the war, what happened out there in the bush; like Pontius Pilate, he will wash his hands clean of it. Or maybe, years later, lying face up on his deathbed in a government hospital — cancer of the prostate, say, or cirrhosis of the liver — the memory of that wartime spring will come back to him. Clear as day as the old saying goes. He will remember the trek through the high grasses and the birds, scattered in the trees, startled suddenly into flight… The artist’s grandfather spoke very little about his wartime experience, only that ‘he hated the war’, and that the enemy they were shooting at were ‘just kids.’ Perhaps like me, these silences or fragments of a story, make you think about your grandmother. She, too, had come through slaughter and could not bring herself to talk about it. Yet she is also there when I close my eyes. She spots the gunman and his accomplices crouched in the grass, signalling to each other like hunters closing in on their prey. She lets out a scream, but it is too late. The house is surrounded. She narrowly escapes, but glances over her shoulder in time to see the men push her husband to the ground. In that moment, she decides she will never return home again. She runs through fields, bush, crawls under barbed wire and watches the day turn into night along a narrow steep-sided ravine. Sunrise finds her walking under an ochre sky along a gravel road, with only the clothes on her back, when a 1967 Austin A110 Westminster pulls over. The driver, a quiet and melancholy man, doesn’t ask too many questions, only offers the woman a lift. Says he’s driving to the capital. She nods, opens the door, slides into the passenger seat. Twenty minutes later, say, the driver of the 1967 Austin A110 Westminster and the woman — who is and is not your grandmother — are waved to a stop at a military checkpoint. Large swathes of this territory are under martial law. The soldiers — young men dressed in brown and green army fatigues, with clean shaven faces and regulation haircuts — bark orders at them to get out of the vehicle while they search for weapons, explosives, contraband. Terrorists. Afterward, when they’re cleared to pass, the woman hears the driver whisper to himself, whatever else happens to us. He nods at the young man standing on the roadside, a rifle fitted with a bayonet slung over his shoulder, we are war people… One problem with war, for those of us who did not live through it, is its vast scale. Upwards of 70 million people, more than the entire population of South Africa, perished during World War II. How does one even begin to understand a catastrophe of this scale beyond the gargantuan task of creating “an elaborate encyclopaedia of the dead, telling precisely how each killing happened, and what the consequences were”. To be able take the measure of it, to weigh its mass, perhaps one has to narrow the parameters, to a single gunshot fired by a .38 revolver, or to a nail made from a Second World War African Service medal. Someday, when I sit down to write this story, I will begin with my mother or the woman who will one day be my mother. She is all of twenty years old, a trainee nurse during a time of civil war. Upon hearing the news of her father’s abduction, she will abandon her shift without informing her supervisor and head to the main bus terminal. She will stay there until dusk, and even longer, until the sky above the capital is dotted with stars. For three days straight, she will return to this exact spot at daybreak, and each time her vigil ends long after curfew. She is hoping to see her father, spared by the gunman and his accomplices, stepping off one of the buses filled with passengers seeking refuge in the city. But nothing of that sort happens. She doesn’t know it yet, or perhaps deep down she does, but she will never see her father again. Decades later, when asked about the war, my mother will say, there are times when I feel that it’s over and other times, when it feels like it is just beginning.To an Unknown Visitor at the Gallery

Words by B. K.

Words by B. K.

“all wars are fought twice, the first time on the battlefield, the second time in memory.”